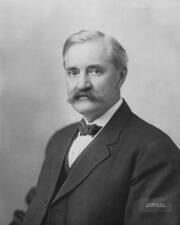

Senator Albert Baird Cummins

Here you will find contact information for Senator Albert Baird Cummins, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | Albert Baird Cummins |

| Position | Senator |

| State | Iowa |

| Party | Republican |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | November 24, 1908 |

| Term End | July 30, 1926 |

| Terms Served | 4 |

| Born | February 15, 1850 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | C000988 |

About Senator Albert Baird Cummins

Albert Baird Cummins (February 15, 1850 – July 30, 1926) was an American lawyer, progressive reformer, and Republican politician who served as the 18th governor of Iowa and as a United States Senator from Iowa from 1908 to 1926. Over the course of 18 years in the Senate—spanning four terms—he became one of the most prominent Midwestern progressives of the early twentieth century, later evolving into a more conservative “New Era” Republican. He is also remembered for his service as president pro tempore of the Senate from 1919 to 1925 and for his repeated, though unsuccessful, bids for the Republican presidential nomination.

Cummins was born in a log house in Carmichaels, Greene County, Pennsylvania, the son of Sarah Baird (Flenniken) Cummins and Thomas L. Cummins, a carpenter who also farmed. He attended various local schools, including the Greene Academy at Carmichaels, and matriculated at Waynesburg College. Although he completed the required coursework, he did not receive a degree, reportedly due to a dispute with the college president over Darwinism. After leaving college, he worked as a tutor and taught at a country school. At age nineteen he moved with his maternal uncle to Elkader, Iowa, where he found employment in the Clayton County recorder’s office and also worked as a carpenter. In 1871 he relocated to Allen County, Indiana, where he held a series of positions as a railway clerk, carpenter, construction engineer, express company manager, and deputy county surveyor, gaining practical experience in business and infrastructure work that would later inform his views on transportation and regulation.

In the mid-1870s Cummins turned to the law. He moved to Chicago, Illinois, where he studied law while clerking in an attorney’s office, and he was admitted to the Illinois bar in 1875. After three years of practice in Chicago, he moved to Des Moines, Iowa, and established a law practice that quickly prospered. Early in his legal career he largely represented businessmen and corporations, which brought him financial success and prominence in Des Moines society. His most famous case, however, placed him on the side of small producers: he represented a group of Iowa farmers associated with the Grange movement in litigation against Washburn and Moen, a barbed-wire trust. The farmers sought to break an eastern syndicate’s monopoly on barbed-wire production by running their own factory. Although historians generally regard this case as an exception—since Cummins more often represented corporate interests—it helped shape his public image as a defender of the common man against monopolistic power.

Cummins’s political activity developed alongside his legal career. Identifying with the Republican Party, he became active first in state and then in national politics. He attended every state and national Republican convention between 1880 and 1924, reflecting his long-standing engagement with party affairs. In 1887 he was elected to a single term in the Iowa State Senate representing Des Moines, serving from 1888 to 1890. He served as a presidential elector in 1892 and was chosen as temporary chair of the 1892 Iowa Republican State Convention. Although he unsuccessfully sought a U.S. Senate seat in 1894, he remained influential within the party. From 1896 to 1900 he served as Iowa’s representative on the Republican National Committee and was active in William McKinley’s 1896 presidential campaign. During the 1890s he emerged as the leader of the progressive “insurgent” wing of the Iowa Republican Party, challenging the long-dominant “standpat” establishment represented by Senator William B. Allison, Congressman David B. Henderson, and Representative William P. Hepburn.

Cummins’s rise to statewide executive office followed several near-misses in the contest for a U.S. Senate seat. In early 1900, when the Iowa General Assembly still chose U.S. senators, he opposed incumbent Republican Senator John H. Gear for the Class 2 seat for the 1901–1907 term but withdrew when it became clear he lacked sufficient legislative support. After Gear’s death in July 1900, Governor Leslie M. Shaw declined appeals to appoint Cummins to the vacancy and instead named Jonathan P. Dolliver. Cummins initially vowed to pursue the Senate seat again in the 1901 legislative session, but he shifted his focus to the governorship. He was elected governor of Iowa in 1901 and served from 1902 to 1908, becoming the first Iowa governor elected to three consecutive terms. As governor he championed a broad progressive agenda, including the establishment of compulsory education, the creation of a state department of agriculture, and the institution of a system of primary elections. His reforms also included establishing the direct primary to allow voters, rather than party bosses, to select candidates; outlawing free railroad passes for politicians; imposing a two-cent maximum fare on street railways; and abolishing corporate campaign contributions in state politics. These measures made him perhaps the most influential and charismatic progressive leader in Iowa politics in the first quarter of the twentieth century.

During his gubernatorial years Cummins became identified with the “Iowa idea,” an influential approach to tariff and regulatory policy. As articulated in the Iowa Republican Party’s 1902 platform, the “Iowa idea” called for amendments to the Interstate Commerce Act to strengthen its prohibition of discrimination in ratemaking and for modifications of tariff schedules to prevent them from sheltering monopolies. The principle held that tariff rates should reflect the difference between the cost of production at home and abroad, but should not be set higher than necessary to protect domestic industries. Cummins’s efforts to lower the high protective tariff in Washington met with limited success, but they underscored his broader campaign to break up monopolies and curb corporate power.

Cummins entered the United States Senate during a period of transition in both Iowa and national politics. In June 1908, while still governor, he challenged Senator William B. Allison in the Republican primary for Allison’s seat and was accused of breaking an earlier promise not to run against the veteran senator. He lost the primary by more than 12,000 votes. However, Allison died on August 4, 1908, before the Iowa General Assembly could act on the primary results. A second Republican primary was held in November 1908, which Cummins won decisively. Later that month, and again in January 1909, the Iowa General Assembly elected him over Democratic rival Claude R. Porter. He took his seat in 1908 and served as U.S. Senator from Iowa until his death in 1926, a span of 18 years that encompassed four terms and some of the most consequential events of the Progressive Era and World War I. During his Senate career he chaired the Committee on Interstate Commerce and the Senate Judiciary Committee, and from 1919 to 1925 he served as president pro tempore of the Senate, placing him high in the line of presidential succession and underscoring his seniority and influence.

In Congress Cummins continued to pursue progressive economic regulation, though his stance evolved over time. He generally supported President Woodrow Wilson’s initiatives to regulate business and was associated with antitrust efforts, being credited with authoring a clause of the Sherman Antitrust Act. He played a central role in transportation policy as chair of the Committee on Interstate Commerce. In the aftermath of World War I, he co-sponsored the Esch–Cummins Act of 1920, which established the terms under which the nation’s railroads, operated by the federal government during the war, were returned to private control. The act strengthened the Interstate Commerce Commission’s authority but was criticized by labor activists for its restrictive provisions on collective bargaining, including language that made it a crime to encourage a railroad strike outside of wartime emergency conditions. This legislation symbolized Cummins’s postwar break with the progressive movement and marked his shift from the insurgent progressivism of Robert M. La Follette toward the more conservative Republicanism associated with President Warren G. Harding.

Cummins also played a visible role in national electoral politics. In January 1912 he announced his intention to seek the Republican presidential nomination and was considered a potential candidate at the 1912 Republican National Convention. Amid the tumult that followed the walkout of Theodore Roosevelt’s supporters, however, his name was never formally placed in nomination. In the ensuing general election he supported Roosevelt rather than President William Howard Taft, even while opposing Roosevelt’s decision to form a third party. Cummins again sought the Republican presidential nomination in 1916. At the 1916 Republican National Convention, with no incumbent Republican president, the delegates were initially divided among more than a dozen candidates; Cummins finished fifth on the first and second ballots before releasing his delegates, contributing to the eventual nomination of Supreme Court Justice Charles Evans Hughes on the third ballot.

On foreign policy, Cummins generally aligned with his party but showed some independence. He voted in favor of the United States declaration of war on Germany in April 1917 at President Wilson’s request, but he opposed the arming of merchant ships earlier that year and later resisted U.S. membership in the League of Nations in 1919 and 1920. His stance reflected the broader skepticism among many Republicans about permanent international commitments, even as they supported a strong national defense. Over time, his positions placed him more firmly within the mainstream of postwar Republican conservatism, distancing him from the progressive insurgents with whom he had once been closely allied.

Cummins’s long Senate career ended amid intra-party conflict. In June 1926, insurgent Republican Smith W. Brookhart defeated him in the Republican primary for his Senate seat. Brookhart had only recently been unseated from Iowa’s other U.S. Senate seat after the Republican-controlled Senate voted to sustain Democrat Daniel F. Steck’s challenge to the 1924 Brookhart–Steck election. Cummins had declined to take a public position on that contested election, aware that if Brookhart were removed he might seek Cummins’s seat. The primary defeat underscored the extent to which Cummins’s shift away from progressivism had eroded his support among Iowa’s insurgent Republicans. The following month, on July 30, 1926, he died in Des Moines while still in office, placing him among the members of Congress who died in office between 1900 and 1949. He was interred at Woodland Cemetery in Des Moines. His residence, the Albert Baird Cummins House in Des Moines, is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

On June 24, 1874, Cummins married Ida Lucette Gallery. The couple had one child, a daughter. Ida L. Cummins was herself a notable public figure in Iowa, active in the woman suffrage movement and highly influential in the development of Iowa’s child labor laws. Her reform work paralleled and complemented her husband’s early progressive agenda. Together, their careers reflected the intertwined currents of political and social reform that shaped Iowa and national politics in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.