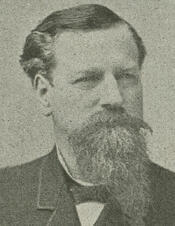

Representative Alexander Monroe Dockery

Here you will find contact information for Representative Alexander Monroe Dockery, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | Alexander Monroe Dockery |

| Position | Representative |

| State | Missouri |

| District | 3 |

| Party | Democratic |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | December 3, 1883 |

| Term End | March 3, 1899 |

| Terms Served | 8 |

| Born | February 11, 1845 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | D000384 |

About Representative Alexander Monroe Dockery

Alexander Monroe Dockery (February 11, 1845 – December 26, 1926) was an American physician, banker, and Democratic politician who served as a Representative from Missouri in the United States Congress from 1883 to 1899 and as the 30th governor of Missouri from 1901 to 1905. Over eight consecutive terms in the House of Representatives, he represented Missouri’s 3rd Congressional District and became known as a leading fiscal conservative. According to one observer, Dockery generally disdained “the progressive-reform impulses that were in ascendancy at the dawn of the new century,” a stance that shaped his approach to both congressional and gubernatorial service.

Dockery was born the only child of Willis E. Dockery and Sarah Ellen Dockery near Gallatin, Daviess County, Missouri. His father, a Methodist minister, was among the early settlers of the county, and the family’s frontier setting and religious background influenced Dockery’s early life. He attended local public schools in and around Gallatin before enrolling for a brief period at Macon Academy in Macon, Missouri. Pursuing a medical career, he entered St. Louis Medical College (now part of Washington University School of Medicine) and graduated on March 2, 1865, near the close of the Civil War. Shortly thereafter he established a medical practice in Linneus, Missouri, and undertook post-graduate study during the winter of 1865–1866 through lectures at Bellevue College in New York City and Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia. After returning to his practice in Linneus, he later moved to Chillicothe, Missouri, where his professional and civic profile expanded.

While practicing medicine in Chillicothe, Dockery married Mary Elizabeth Bird in 1869. He soon began to combine medical work with public service. From 1870 to 1874 he served as county physician for Livingston County, Missouri, and from 1871 to 1873 he was president of the Chillicothe Board of Education, an early indication of his interest in educational policy. In 1872 he commenced a ten-year tenure as a member of the Board of Curators of the University of Missouri, participating in the governance of the state’s principal public university. In March 1874 Dockery ended his medical practice and returned to his native Gallatin to embark on a new career in banking. Initially intending to establish a bank in Milan, Missouri, he instead joined his Chillicothe associate Thomas Yates in founding and operating the Farmers Exchange Bank in Gallatin. As cashier and treasurer of the bank, Dockery developed financial and money-management skills that would later underpin his reputation for fiscal expertise in Congress and as governor.

Dockery’s formal political career began at the local level. He was elected to the Gallatin City Council in 1878 and served as mayor of Gallatin from 1881 to 1883. During this period he became increasingly active in Democratic Party affairs, serving as chairman of the congressional committee of his district. In 1882, leveraging his local prominence and party work, he ran for the United States House of Representatives. In the November 1882 election he defeated incumbent Representative Joseph H. Burrows of the Greenback Party and Republican candidate James H. Thomas, winning 52.9 percent of the vote. Taking his seat in March 1883, he began a sixteen-year tenure in Congress, ultimately serving eight terms and representing the interests of his Missouri constituents during a significant period in American political and economic development.

In the House of Representatives, Dockery quickly established himself as a staunch fiscal conservative and earned the sobriquet “Watchdog of the Treasury” during his ten years on the powerful House Appropriations Committee. He articulated his philosophy with the oft-quoted statement: “Unnecessary taxation leads to surplus revenue, surplus revenue begets extravagance, and extravagance sooner or later is surely followed by corruption.” Drawing on his banking experience, he played a key role in the Treasury Department’s modification and modernization of its accounting practices. Dockery also served as chairman of the Committee on Expenditures in the Post Office Department, where he pressed for greater fiscal responsibility and administrative reforms that improved mail delivery, particularly in rural areas. An ardent supporter of Rural Free Delivery, he backed its implementation in the 1890s, helping to extend postal services to isolated farm communities. He opposed high protective tariffs, arguing that they harmed farm exports and rural interests. During his congressional service he participated in deliberations on major legislation, including the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887 and the Hatch Act, and he voted on measures related to the Spanish–American War. After eight terms in Congress, Dockery chose not to run for reelection in 1898, completed his service in March 1899, and returned to Gallatin to prepare for a gubernatorial campaign.

In the Missouri gubernatorial election of November 1900, Dockery secured the Democratic nomination and faced Republican Joseph Flory and four other candidates. He won the governorship with a narrow majority of approximately 51 percent of the vote and took office in January 1901. As governor, Dockery applied his long-standing fiscal principles to state government. His administration worked to increase funding for public education and to establish more systematic school districting across Missouri. He supported election reforms and oversaw the enactment of a franchise tax law that broadened the state’s revenue base. Through increased revenues and changes in fiscal management—hallmarks of his public career—Missouri’s bonded indebtedness was paid off during his term. On March 23, 1903, Dockery signed the first state legislation in the nation licensing automobiles, requiring drivers to ring a bell or sound a horn or whistle before passing horse-drawn vehicles and setting a statewide speed limit of nine miles per hour, a “Missouri first” in motor-vehicle regulation. As governor he also served as host to numerous national and international dignitaries during the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition (St. Louis World’s Fair), which brought worldwide attention to the state.

Dockery’s gubernatorial tenure coincided with the rise of progressive reform in Missouri politics, a movement he largely distrusted. The Missouri constitution barred him from seeking a second consecutive term, and he left office in early January 1905, succeeded by fellow Democrat Joseph W. Folk, a reform-minded prosecutor from St. Louis. Dockery strongly disagreed with Folk’s anti-patronage, anti-cronyism agenda and questioned his loyalty to the Democratic Party. During the intraparty struggle leading up to Folk’s nomination, Dockery lobbied hard against him, while Folk charged that the Dockery administration had tolerated or enabled intimidation of Folk supporters at St. Louis polling places during the Democratic primary. Folk contended that Dockery was either unable or unwilling to control the St. Louis police. The conflict was ultimately resolved at the state Democratic convention in what was dubbed a second “Missouri Compromise,” under which Dockery extended only tepid support to Folk. Folk and his reform allies prevailed, signaling a shift in Missouri politics away from the “old guard” Democratic organization with which Dockery had been associated. During this period Dockery also suffered personal loss: his wife, Mary Elizabeth Bird Dockery, died in 1903, and all of their children had died in early childhood.

After leaving the governorship and now a widower, Dockery returned to Gallatin for what he initially envisioned as a life of semi-retirement. He remained active in local civic affairs and took a personal interest in infrastructure, particularly road maintenance. Residents of Daviess County’s Union Township frequently saw him personally engaged in road repair, driving a horse and wagon to patch potholes and fix culverts. Despite his earlier clash with Joseph Folk, Dockery continued to participate in state Democratic politics, serving as treasurer of the Democratic State Committee in 1912 and 1914. His retirement from national office ended in 1913 when, during a trip to Washington, D.C., to attend the inauguration of President Woodrow Wilson, he was asked by the new administration to assist in managing and streamlining the United States Postal Service. Appointed third assistant Postmaster General, Dockery applied his financial and administrative expertise to putting the agency’s fiscal operations in order. He served in that capacity until March 31, 1921, contributing to the modernization and stabilization of postal finances during a period of rapid growth in federal services.

In his final years, Dockery again retired to Gallatin, where he devoted himself to philanthropy and community life. With his wife deceased and their children all having died young, he directed his paternal impulses toward the children of the community. He made a substantial donation of books and funds that helped establish and enrich the Gallatin High School library, and he donated a 13-acre tract of land to be used as a public park. The town honored him annually with “Dockery Day” on his birthday, when local schoolchildren received free admission to the town theater at his expense. Alexander Monroe Dockery died on December 26, 1926, and was buried in Edgewood Cemetery in Chillicothe, Missouri. His long career as a physician, banker, legislator, governor, and federal administrator left a lasting imprint on Missouri’s political and civic life.