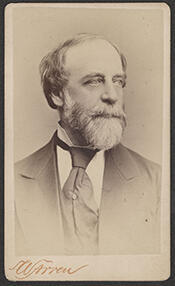

Representative Alexander Hamilton Rice

Here you will find contact information for Representative Alexander Hamilton Rice, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | Alexander Hamilton Rice |

| Position | Representative |

| State | Massachusetts |

| District | 3 |

| Party | Republican |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | December 5, 1859 |

| Term End | March 3, 1867 |

| Terms Served | 4 |

| Born | August 30, 1818 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | R000193 |

About Representative Alexander Hamilton Rice

Alexander Hamilton Rice (August 30, 1818 – July 22, 1895) was an American politician and businessman from Massachusetts who served as Mayor of Boston from 1856 to 1857, a U.S. Representative from Massachusetts from 1859 to 1867 during the American Civil War, and the 30th Governor of Massachusetts from 1876 to 1879. A member of the Republican Party, he was part owner and president of Rice-Kendall, one of the nation’s largest paper products distributors, and became a prominent figure in both the commercial and political life of Massachusetts.

Rice was born in Newton Lower Falls, Massachusetts, on August 30, 1818, to Thomas and Lydia (Smith) Rice. His father, a native of Brighton, owned a paper manufacturing business in Newton, and both parents traced their ancestry to early colonial families of New England. His uncle Charles Rice was a brigadier general in the Massachusetts state militia and also served as a state legislator, giving the family a tradition of public service. Rice attended the public schools of Newton and later private schools in Needham and Newton. As a young man he clerked in a Boston dry goods store before apprenticing with the Boston paper distributor Wilkins, Carter & Company, an experience that drew him into the paper trade that would underpin his later business success.

In 1840 Rice entered Union College in Schenectady, New York, where he distinguished himself academically and graduated as class valedictorian in 1844. That same year he suffered a serious fall from a horse that disfigured his face and left him with a speech impediment. The injury led him to abandon an intended career in law and to concentrate instead on business pursuits. Over time he overcame his speech difficulties and eventually became known as a commanding and effective public speaker. Returning to Massachusetts, he built on his family’s connections in the paper industry, becoming part owner and president of Rice-Kendall, which grew into one of the largest paper products distributors in the United States and provided him with the financial independence to enter public life.

Rice’s political career began in Boston municipal government. In 1853 he was elected to the Boston City Council from the eleventh ward and served for two years, acting as council president in 1854. That same year he served as president of the Boston School Committee, reflecting his early interest in civic administration and public education. In 1856 he was elected mayor of Boston as a “Citizens” candidate opposed to the nativist Know Nothing movement, and he served two one-year terms from 1856 to 1857. As mayor he helped broker a landmark agreement among the city, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, and private owners of a tidal waterworks that initiated the development of Boston’s Back Bay, then a malodorous tidal flat used as a dumping ground. The arrangement authorized construction of what is now Arlington Street and reserved as parkland the area between Arlington Street and Charles Street, which became the Boston Public Garden. During and after his mayoralty he served on committees responsible for commissioning and installing the statues of George Washington and Charles Sumner in the Public Garden. He also authorized construction of Boston’s first city hospital and oversaw the conversion of the city almshouse on Deer Island into an insane asylum and workhouse after the state assumed responsibility for the indigent.

Rice participated in the founding of the Republican Party in Massachusetts and soon moved onto the national stage. He was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1858 and served four consecutive terms from March 4, 1859, to March 3, 1867, representing Massachusetts as a Republican during one of the most consequential periods in American history. During his eight years in Congress he contributed to the legislative process as a member of the House of Representatives and represented the interests of his Massachusetts constituents through the secession crisis, the Civil War, and the early years of Reconstruction. In January 1861 he introduced in the House the Crittenden Compromise, a last-ditch effort to avert civil war by constitutionally protecting slavery in certain territories; his speech in support of the measure received a lukewarm reception and the proposal failed. During the war he served as chairman of the Committee on Naval Affairs from 1863 to 1865, exercising oversight of naval policy and procurement at a time when the Union Navy was expanding rapidly. Ideologically, Rice was regarded as a conservative Republican who opposed many of the Radical Republicans’ positions on the abolition of slavery and Reconstruction policy, and he was viewed by labor interests as favoring the “moneyed class.” After the war, in recognition of his support for the Union cause, he was elected a Third Class Companion of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States. He declined to stand for reelection in 1866 and left Congress at the close of his fourth term in 1867.

After his congressional service, Rice stepped back from elective office and devoted himself to his business affairs and civic activities. He continued to lead Rice-Kendall and remained influential in Boston’s commercial community. In 1871 he was among several contenders for the Republican nomination for governor of Massachusetts, in a contest dominated by Benjamin Butler and ultimately won by William B. Washburn. Following the Great Boston Fire of November 1872, Rice served on a relief committee that helped address the city’s recovery and rebuilding needs, further enhancing his reputation as a capable civic leader. These activities kept him in public view and positioned him for a return to high office.

In 1875 Rice secured the Republican nomination for governor and defeated the incumbent Democrat William Gaston in the general election. He served three one-year terms as the 30th Governor of Massachusetts from 1876 to 1879 before retiring permanently from politics. As governor he supported a range of social reform measures and labor protections, including legislation establishing a minimum age of fourteen for factory work, an important step in the regulation of child labor. He advocated improvements in social conditions and sought, though unsuccessfully, to reorganize the state’s major charitable institutions. Rice allowed the state’s “local option” alcohol law to remain in force, a stance that drew criticism from temperance advocates who favored more stringent statewide prohibition. He also chaired a committee formed in 1876 to prevent the demolition of Boston’s historic Old South Meeting House; through the committee’s efforts, ownership of the building was transferred to a nonprofit organization dedicated to its preservation, marking an early milestone in the historic preservation movement in Boston.

One of the most controversial issues of Rice’s gubernatorial tenure involved the case of Jesse Pomeroy, a juvenile convicted murderer. Pomeroy, then fourteen years old, had been convicted in December 1874 of first-degree murder for killing a young girl earlier that year and was sentenced to death. Public opinion strongly favored his execution, especially after an attempted prison escape. Governor Gaston, Rice’s predecessor, had twice refused to sign the execution warrant despite recommendations from the Governor’s Council that clemency be denied, a decision that likely damaged Gaston politically and contributed to Rice’s victory in 1875. As governor, Rice also declined to sign the execution order, but under his administration the Council ultimately recommended commutation of Pomeroy’s sentence to life imprisonment in solitary confinement, a resolution that kept the case at the center of public debate over juvenile crime and capital punishment.

In his later years Rice lived quietly, dividing his time between his business interests and social and civic engagements. He remained a respected elder statesman within Massachusetts Republican circles, though he did not again seek public office after leaving the governorship in 1879. Alexander Hamilton Rice died at the Langwood Hotel in Melrose, Massachusetts, on July 22, 1895, after a lengthy illness. He was buried in Newton Cemetery in his native Newton, closing the life of a businessman-turned-politician who had played a significant role in Boston’s urban development, the Union war effort in Congress, and the political life of Massachusetts in the mid-nineteenth century.