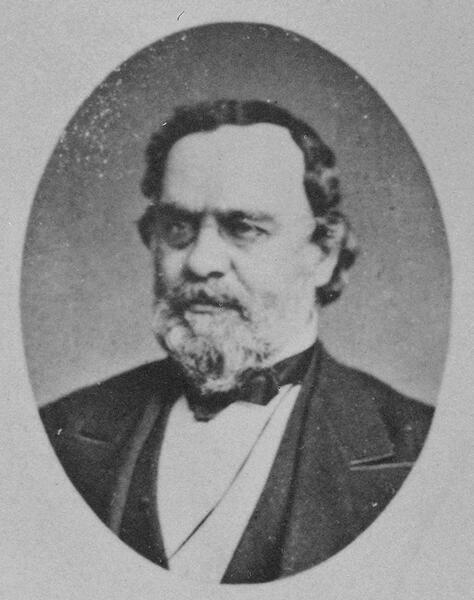

Representative Alpheus Starkey Williams

Here you will find contact information for Representative Alpheus Starkey Williams, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | Alpheus Starkey Williams |

| Position | Representative |

| State | Michigan |

| District | 1 |

| Party | Democratic |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | December 6, 1875 |

| Term End | March 3, 1879 |

| Terms Served | 2 |

| Born | September 20, 1810 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | W000487 |

About Representative Alpheus Starkey Williams

Alpheus Starkey Williams (September 20, 1810 – December 21, 1878) was a lawyer, judge, journalist, U.S. congressman, and Union general in the American Civil War who later represented Michigan in the United States House of Representatives from 1875 until his death in 1878. A member of the Democratic Party, he contributed to the legislative process during two terms in office and played a significant role in both military and political affairs during a transformative period in American history.

Williams was born on September 20, 1810, in Deep River, Connecticut. His father died when he was eight years old, leaving him a sizable inheritance that would shape his early adulthood. He pursued higher education at Yale University, from which he graduated with a law degree in 1831. Between 1832 and 1836, he used his inheritance to travel extensively throughout the United States and Europe, broadening his experience and perspective before embarking on a professional career. In 1836 he settled in Detroit, Michigan, then a rapidly growing frontier city, where he established himself as a lawyer. He married Jane Hereford Larned, the daughter of a prominent Detroit family, and the couple had five children, two of whom died in infancy. Jane Williams died in 1848 at the age of 30, leaving him a widower with surviving children to raise.

In Detroit, Williams pursued a varied and increasingly prominent civic and professional career. He was elected probate judge of Wayne County, Michigan, and in 1842 became president of the Bank of St. Clair. The following year, in 1843, he became owner and editor of the Detroit Advertiser, a daily newspaper, reflecting his interest in public affairs and journalism. From 1849 to 1853 he served as postmaster of Detroit, a federal appointment that further enhanced his standing in the community. At the same time, he maintained a strong connection to military affairs. Shortly after his arrival in Detroit in 1836, he joined a company in the Michigan Militia and remained active in the city’s military circles for years. In 1847 he was appointed lieutenant colonel of the 1st Michigan Infantry for service in the Mexican–American War, but the regiment arrived too late to see combat. He later served as president of Michigan’s state military board and, by 1859, held the rank of major in the Detroit Light Guard.

At the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, Williams was deeply involved in organizing and training Michigan’s first army volunteers. He was appointed brigadier general of volunteers on May 17, 1861. His initial field assignment was as a brigade commander in Major General Nathaniel P. Banks’s division of the Army of the Potomac from October 1861 to March 1862. On March 13, 1862, he assumed command of a division in the V Corps of the Army of the Potomac, which was transferred to the Department of the Shenandoah from April to June 1862. In the Shenandoah Valley, Williams and Banks were sent against Major General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson but were outmaneuvered and effectively bottled up by Jackson’s smaller Confederate force. On June 26, 1862, Williams’s division was transferred to Major General John Pope’s Army of Virginia for the Northern Virginia Campaign. At the Battle of Cedar Mountain, Banks’s corps again faced Jackson and was defeated; Williams’s command was at Bristoe Station during the Second Battle of Bull Run and did not take part in that engagement.

Williams’s division subsequently rejoined the Army of the Potomac as the 1st Division of the XII Corps and marched north in the Maryland Campaign, culminating in the Battle of Antietam. En route, soldiers from his division discovered the famous Confederate “lost dispatch,” Special Order 191, which revealed General Robert E. Lee’s operational plan and provided Major General George B. McClellan with critical intelligence about the divided Confederate army. At Antietam, Williams’s division was heavily engaged at Sharpsburg on the Union right, again confronting Jackson’s forces on the Confederate left. When XII Corps commander Major General Joseph K. Mansfield was killed early in the battle, Williams assumed temporary command of the corps. The XII Corps suffered about 25 percent casualties in its assaults, and Brigadier General George S. Greene’s division was compelled to withdraw from advanced positions near the Dunker Church. After the battle, McClellan assigned Major General Henry W. Slocum permanent command of XII Corps, and Williams returned to division command. His division missed the Battle of Fredericksburg while assigned to reserve duty guarding the Potomac River, but at the Battle of Chancellorsville on May 2, 1863, his troops hastily entrenched and helped halt the Confederate flanking attack that had routed the neighboring XI Corps, suffering roughly 1,500 casualties in the process.

Williams’s division played a central role in the Gettysburg Campaign. Arriving late on July 1, 1863, his men occupied Benner’s Hill east of Gettysburg and, on July 2, took up positions on Culp’s Hill, anchoring the right flank of the Union line. Because Slocum believed he commanded the “Right Wing” of the army, consisting of the XI and XII Corps, Williams assumed temporary command of XII Corps for the remainder of the battle, while Brigadier General Thomas H. Ruger led his division. When a massive Confederate assault under Lieutenant General James Longstreet struck the Union left on the afternoon of July 2, Major General George G. Meade ordered XII Corps to reinforce that sector. Williams persuaded Meade to leave one brigade, under Greene, on Culp’s Hill. Greene’s brigade held off repeated attacks by Major General Edward “Allegheny” Johnson’s division through the night, preserving the Union right until the rest of XII Corps returned. Early on July 3, Williams directed attacks that drove the Confederates from portions of the Culp’s Hill entrenchments after a prolonged, seven-hour struggle, restoring the Union line. Despite the importance of these actions, Williams’s and XII Corps’s contributions were not fully acknowledged in Meade’s official report, in part because Slocum was late in submitting his own account.

In the autumn of 1863, following the Union defeat at the Battle of Chickamauga, the XI and XII Corps were ordered west to reinforce the besieged Army of the Cumberland at Chattanooga. The two understrength corps were later consolidated into the XX Corps of the Army of the Cumberland. Williams’s division initially guarded railroads in eastern Tennessee and did not participate directly in the relief of Chattanooga, but it later joined Major General William T. Sherman for the Atlanta Campaign. Under the XX Corps banner, his division fought with distinction in several engagements, notably the Battle of Resaca. Williams was wounded in the arm at the Battle of New Hope Church on May 26, 1864. His division then accompanied Sherman on the March to the Sea and through the Carolinas Campaign. During these operations, Williams at times commanded the entire XX Corps until, after the Battle of Bentonville, Major General Joseph A. Mower was assigned to corps command and Williams resumed divisional leadership. He received a brevet promotion to major general on January 12, 1865. Over the course of the war, he became the longest-serving division commander in the Union army, continuously leading his division from March 13, 1862, to the end of hostilities, aside from brief periods of corps command and temporary absences. He led his division in the Grand Review of the Armies in Washington, D.C., in May 1865. Despite his seniority and record of reliable service, he never received a full promotion beyond brigadier general nor permanent command of a corps, a circumstance often attributed to his non–West Point background, his early service away from the main Army of the Potomac high command, and his reluctance to engage in self-promotion through the press.

Williams’s wartime service was also remembered for his close association with his horses, particularly Yorkshire and Plug Ugly. Yorkshire was the more showy mount, but Williams often chose the larger Plug Ugly for difficult or extended duty. At the Battle of Chancellorsville, a Confederate shell exploded in the mud beneath Plug Ugly, hurling both horse and rider into the air. Williams emerged uninjured, and the horse suffered only minor wounds. By 1864, however, Plug Ugly was worn out from service; Williams sold him for $50 and later learned that the horse died not long afterward. Williams himself was an articulate observer of the war, and his extensive correspondence with his family was preserved and published posthumously in 1959 under the title From the Cannon’s Mouth: The Civil War Letters of General Alpheus S. Williams, offering historians a detailed, personal account of his experiences.

After the Civil War, Williams remained in federal service for a time as a military administrator in southern Arkansas, a position he held until he left the army on January 15, 1866. Returning to Michigan, he encountered financial difficulties that compelled him to seek further government employment. He was appointed United States Minister to San Salvador (El Salvador), serving in that diplomatic post until 1869. In 1870 he ran unsuccessfully for governor of Michigan. Remaining active in Democratic Party politics, he continued to be a prominent figure in Detroit and state affairs.

Williams was elected as a Democrat to the Forty-fifth Congress from Michigan’s 1st congressional district and served in the U.S. House of Representatives from March 4, 1875, until his death on December 21, 1878. His service in Congress coincided with the later years of Reconstruction and the nation’s adjustment to the postwar order. As a member of the House of Representatives, he participated in the legislative process and represented the interests of his Detroit-area constituents. During part of his tenure he served as chairman of the Committee on the District of Columbia, giving him a role in overseeing matters affecting the nation’s capital. His congressional career ended abruptly when he suffered a stroke and died in the U.S. Capitol Building on December 21, 1878, while still in office. He was interred in Elmwood Cemetery in Detroit.

In later assessments, Williams has often been described as a capable but underrecognized general who never received the public acclaim accorded to many of his contemporaries. Observers have attributed this to his lack of a West Point education, his relative isolation from the Army of the Potomac’s early inner circles, and his disinclination to cultivate newspaper correspondents to advance his reputation. Nonetheless, his military and political legacies have been commemorated in various ways. An equestrian memorial by sculptor Henry Shrady stands in Belle Isle Park in Detroit, honoring his service to his adopted city and the Union cause, and Williams Avenue in Gettysburg National Military Park bears his name, marking his role in the pivotal battle fought there.