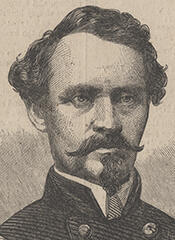

Representative Alvin Peterson Hovey

Here you will find contact information for Representative Alvin Peterson Hovey, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | Alvin Peterson Hovey |

| Position | Representative |

| State | Indiana |

| District | 1 |

| Party | Republican |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | December 5, 1887 |

| Term End | March 3, 1889 |

| Terms Served | 1 |

| Born | September 6, 1821 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | H000833 |

About Representative Alvin Peterson Hovey

Alvin Peterson Hovey (September 6, 1821 – November 23, 1891) was a Union general during the American Civil War, an Indiana Supreme Court justice, a United States Representative from Indiana, and the 21st governor of Indiana from 1889 to 1891. He was born in Mount Vernon, Indiana, on September 6, 1821, to Abiel and Francis Hovey. His father died while he was still a young boy, and his mother died in 1836, when he was fifteen, leaving him an orphan. His youth was spent in poverty; after being sent to an orphanage following his mother’s death, he received only a basic education before being turned out at age eighteen. Determined to become a lawyer, he worked as a bricklayer by day and studied law at night in the Mount Vernon office of attorney John Pitcher beginning in 1840. After more than three years of study, he was admitted to the bar in 1843 and opened his own law office. He married Mary Ann in 1844, and the couple had five children, of whom only two survived infancy.

Hovey’s legal career quickly brought him into public prominence. In 1849 he was appointed to oversee the estate of William Maclure, a wealthy philanthropist and co-founder of the utopian settlement at New Harmony, Indiana. Maclure’s will directed that his estate be sold and the proceeds used to fund libraries, but his two siblings had seized much of the property, sold it, and absconded with the funds. Hovey filed more than sixty lawsuits to recover the assets and enforce the terms of the will. The litigation attracted considerable press coverage throughout Indiana and enhanced his reputation when the estate ultimately funded the opening of 160 libraries in Indiana and Illinois. His growing stature led to his election as a Democrat in 1850 as a delegate to the Indiana constitutional convention. There he supported a range of educational and governmental reforms but also played a leading role in some of the constitution’s most controversial provisions. He opposed extending suffrage to women and African Americans and successfully proposed a clause barring free Blacks from settling in Indiana, a measure many delegates viewed as a punitive burden on the southern states. He also opposed proposed bankruptcy reforms, arguing they would grant excessive protection to debtors and encourage idleness. Although the new constitution was ratified by the voters, its anti-Black provisions were ruled unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court two years later.

In 1854 Governor Joseph A. Wright appointed Hovey to fill a vacancy on the Indiana Supreme Court until an election could be held. At age thirty-four he was the youngest justice in the court’s history and the only delegate to the 1850 constitutional convention to later serve as a judicial interpreter of the document he had helped draft. His most notable decision came in a case striking down certain local tax laws enacted by townships to increase school funding; Hovey held that the constitution required uniform state funding for public schools. He sought election to retain his seat but was defeated after serving about six months on the bench. In 1855 President Franklin Pierce appointed him United States Attorney for the District of Indiana. During this period the state Democratic Party was riven by internal conflict over slavery. The pro-slavery faction led by Senator Jesse D. Bright gained control of the party apparatus and, at the 1858 state convention, expelled many anti-slavery Democrats, including Hovey. Bright then influenced President James Buchanan to remove Hovey from his federal post. In response, Hovey ran for Congress as an Independent against Democrat William E. Niblack but was defeated by a wide margin. He subsequently joined the Republican Party, along with many other expelled Democrats, and returned to private law practice.

With the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861, Hovey entered military service on the Union side. He was first commissioned a colonel and organized the First Regiment of the Indiana Legion, a state militia force used for home defense. Soon afterward he was appointed colonel of the 24th Indiana Infantry Regiment, which was quickly sent to the front. He led the regiment at the Battle of Shiloh in April 1862 and remained with the advance elements of the principal western Union army. His performance earned him promotion to brigadier general of United States Volunteers. During the siege of Corinth he commanded the 1st Brigade of Lew Wallace’s 3rd Division. In the fall of 1862 he briefly commanded the District of Eastern Arkansas, then returned to brigade command in the Army of the Tennessee. In January 1863 he was given command of the 12th Division of XIII Corps and led it in the Battle of Champion Hill in May 1863, where his aggressive action drew high praise from General Ulysses S. Grant. He again led his division in the subsequent Siege of Vicksburg, a decisive campaign that broke Confederate control of the Mississippi River; Grant again cited Hovey’s division as a key factor in the Union victory.

Hovey’s military service was marked not only by battlefield command but also by his role in internal security in Indiana. After Vicksburg he received word that his wife Mary Ann had died, and he returned home to arrange guardianship for his children, a loss from which he was slow to recover emotionally. He briefly returned to the field in 1864, commanding the 1st Division of XXIII Corps during the Atlanta Campaign. When that division was discontinued in August 1864 and its regiments redistributed, Hovey found himself without a field command and again returned to Indiana. Governor Oliver P. Morton placed him in command of Regular Army and Indiana Legion units in the state, with primary responsibility for recruitment and for suppressing anti-government activity. He raised a division of about 10,000 troops, accepting only unmarried men; because of their youth, the unit became known as “Hovey’s Babies.” His investigations uncovered a clandestine network of southern sympathizers, including the Sons of Liberty and the Knights of the Golden Circle, and he alleged that they planned an uprising in Indianapolis in August 1864. To forestall the plot, he ordered the arrest of dozens of suspects, who were tried before military tribunals. Several received death sentences, later commuted to life imprisonment. After the war, in Ex parte Milligan (1866), the U.S. Supreme Court ruled such military trials of civilians unconstitutional. Hovey was brevetted major general of volunteers before resigning from the Union Army on October 7, 1865.

Following his resignation from the army, Hovey remarried in 1865 to Rosa Alice, the stepdaughter of former Secretary of the Interior Caleb B. Smith, but she fell ill and died shortly before they were to depart for his new diplomatic posting. That same year he was appointed United States Minister to Peru. During his tenure, Peru was embroiled in conflicts with neighboring states and recurrent internal revolutions, and Hovey’s service was complicated by the instability of successive regimes. He spent much of his time determining which faction held power and how best to maintain American diplomatic interests amid frequent changes in government. In 1870 he resigned his post and returned to Mount Vernon, where he resumed his law practice. In 1872 Indiana Republicans attempted to draft him as their candidate for governor, but he declined, stating that he was finished with politics. For the next fourteen years he practiced law privately and remained a respected figure in state Republican circles.

Hovey returned to elective office in the mid-1880s. In 1886 he accepted the Republican nomination for the U.S. House of Representatives and was elected to the Fiftieth Congress, defeating Democrat J. E. McCullough by a vote of 18,258 to 16,907. Alvin Peterson Hovey served as a Representative from Indiana in the United States Congress from March 4, 1887, to March 3, 1889. A member of the Republican Party, he contributed to the legislative process during his single term in office, participating in the democratic process and representing the interests of his Indiana constituents during a significant period in American history. He did not seek renomination in 1888, as he had been nominated by his party for governor. That year he headed the Republican state ticket while fellow Hoosier Benjamin Harrison ran for President. Although Harrison’s popularity in Indiana was considerable, Hovey narrowly won the governorship, defeating Democrat Courtland C. Matson by a plurality of 49 percent to 48.6 percent of the vote, while Democrats retained control of both houses of the Indiana General Assembly. At age sixty-eight, he became the oldest man elected governor of Indiana up to that time.

Hovey’s gubernatorial term was dominated by constitutional and political struggles with the legislature over executive power and by his efforts at legal and electoral reform. In the final year of his predecessor Albert G. Porter’s administration, the General Assembly had enacted a series of statutes curtailing the governor’s authority, particularly his appointment powers. Once in office in 1889, Hovey sought to restore some of these powers through litigation, challenging several of the legislature’s recent enactments. In a key case, the Indiana Supreme Court upheld the legislature’s removal of most gubernatorial appointment powers. However, in another case involving laws that created state boards to control police, fire, and other municipal services—thereby stripping authority from Republican-controlled local governments—the courts ruled in Hovey’s favor and declared the statutes unconstitutional. In a separate dispute over who could appoint the heads of newly created departments, the court ruled against both the governor and the General Assembly, holding that such officials, like other department heads, must be chosen in general elections. Despite these mixed outcomes, Hovey succeeded in advancing one of his principal policy goals: election reform. Indiana had long suffered from pervasive voter fraud and had some of the least restrictive election regulations in the nation. Political parties printed and distributed their own ballots, which they were required to include their opponents on, a system that encouraged deceptive ballot design and vote manipulation. Vote buying had become commonplace and had drawn national attention in connection with Benjamin Harrison’s election. Under Hovey’s leadership, the General Assembly enacted reforms that introduced the secret (Australian) ballot, standardized ballot forms, increased supervision at polling places, and transferred responsibility for ballot preparation from the parties to the state.

As governor, Hovey also addressed lawlessness associated with vigilante “White Cap” groups operating in southern Indiana, particularly in Harrison and Crawford Counties. These organizations, which had earlier been involved in lynchings such as those of the Reno Gang, engaged in extralegal corporal punishment of men accused of neglecting their families, local criminals, and habitual drunkards. Hovey had campaigned on a promise to curb such vigilantism. Once in office he ordered investigations into the White Caps and publicly declared his intention to suppress their activities. Although the investigations did not result in arrests or prosecutions, the heightened scrutiny and threat of state action contributed to a marked decline and eventual cessation of White Cap operations. His term thus combined a defense of executive authority, significant electoral reforms, and efforts to reinforce the rule of law in troubled regions of the state.

In 1891, while still serving as governor, Hovey fell seriously ill. He died in Indianapolis on November 23, 1891, and was succeeded in office by his lieutenant governor, Ira Joy Chase. Hovey’s body lay in state in the Indiana Statehouse, where citizens paid their respects, before being transported to his hometown of Mount Vernon for funeral services. He was interred in Bellefontaine Cemetery near Mount Vernon, Indiana.