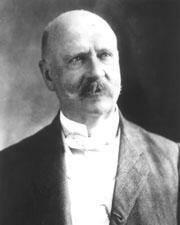

Senator Augustus Octavius Bacon

Here you will find contact information for Senator Augustus Octavius Bacon, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | Augustus Octavius Bacon |

| Position | Senator |

| State | Georgia |

| Party | Democratic |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | December 2, 1895 |

| Term End | March 3, 1915 |

| Terms Served | 4 |

| Born | October 20, 1839 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | B000014 |

About Senator Augustus Octavius Bacon

Augustus Octavius Bacon (October 20, 1839 – February 14, 1914) was a Confederate soldier, segregationist, slave owner, and U.S. politician who represented Georgia in the United States Senate from 1895 until his death in 1914. A member of the Democratic Party, he served four terms in the Senate, became the first senator to be directly elected after the ratification of the Seventeenth Amendment, and rose to the position of president pro tempore of the United States Senate. His long tenure in Congress coincided with a significant period in American history, and he played a prominent role in the legislative process and in representing the interests of his Georgia constituents. After his death, a racially discriminatory provision in his will establishing a “whites only” park in Macon, Georgia, became the subject of two major U.S. Supreme Court decisions during the Civil Rights Movement.

Bacon was born in Bryan County, Georgia, on October 20, 1839. He was of English ancestry and later described himself as an Anglophile, remarking that “all the blood in me comes from English ancestors.” He came of age in the antebellum South, in a slaveholding society in which he himself was a slave owner, and his early life and outlook were shaped by the political and social order of the period. He eventually made his home in Macon, Georgia, which remained his principal residence throughout his political career and where he would later direct that a segregated public park be created under the terms of his will.

Bacon pursued higher education at the University of Georgia in Athens, from which he graduated in 1859. While at the university, he was a member of the Phi Kappa Literary Society, an influential student organization that fostered debate and oratory among future leaders of the state. He then entered the University of Georgia School of Law and was a member of its inaugural graduating class in 1860. His legal training prepared him for a career in law and politics that would span the tumultuous decades before and after the Civil War.

With the outbreak of the American Civil War, Bacon served as a soldier in the army of the Confederate States of America. His Confederate service aligned him with the secessionist cause and the defense of slavery, and it informed his postwar political identity in the Reconstruction and post-Reconstruction South. Following the war and the collapse of the Confederacy, he resumed civilian life in Georgia, practicing law and entering public service as the state adjusted to the new political realities of Reconstruction and the reassertion of white Democratic control.

Bacon’s formal political career began in the Georgia House of Representatives, where he served from 1871 to 1886. During this fifteen-year period, he emerged as a leading figure in state politics and served for much of that time as speaker of the Georgia House. From his base in Macon, he helped shape state legislation in the era of Redemption, when white Democrats reestablished dominance in Georgia’s government and implemented policies that entrenched segregation and disenfranchised African Americans. His prominence in the state legislature positioned him for higher office and reflected the confidence of Georgia Democrats in his leadership.

In 1894, Bacon was elected by the Georgia legislature as one of the state’s United States senators, and he took his seat in the Senate in 1895. He was reelected to three subsequent terms, serving continuously until his death in 1914. During his Senate career, he held several committee chairmanships, including the Committee on Engrossed Bills, the Committee on Private Land Claims, and the influential Committee on Foreign Relations. Although he considered himself an admirer of England and its institutions, he opposed the United States’ emergence as an imperial power along British lines. He was a critic of the Spanish–American War and the subsequent American occupation of the Philippines, arguing against overseas expansion and the acquisition of colonial possessions. His Senate service occurred during a transformative period that included the Progressive Era, debates over U.S. foreign policy, and the institutional reform that culminated in the Seventeenth Amendment.

Bacon’s role in the Senate extended to its internal leadership. During the 62nd Congress, from 1911 to 1913, he served as one of several alternating presidents pro tempore of the United States Senate. This arrangement arose from a compromise under which Bacon, a Democrat, and four Republican senators rotated in the office because neither party could secure a majority vote for a single candidate. In addition to his leadership responsibilities, he took an active interest in the physical and symbolic landscape of the nation’s capital. He was among a number of members of Congress who sought to have prominent streets in Washington, D.C., named after their home states. In 1908 he succeeded in having Brightwood Avenue, also known as Brookeville Pike, renamed Georgia Avenue; the former Georgia Avenue was in turn renamed Potomac Avenue.

Bacon died in office of a coronary occlusion in Washington, D.C., on February 14, 1914, at the age of 74. His death ended nearly two decades of continuous service in the Senate. He was buried in Rose Hill Cemetery in Macon, Georgia. Shortly after his death, Bacon County, Georgia, was established and named in his honor, reflecting the esteem in which many contemporaries in the state held his long public career, despite the deeply segregationist views and policies with which he was associated.

The terms of Bacon’s 1911 will had lasting legal and social consequences. He directed that a park in Macon, known as Baconsfield Park, be established as a “whites only” facility and held in trust by the city. During the Civil Rights Movement, this racially restrictive provision became the focus of two landmark Supreme Court cases. In Evans v. Newton (1966), the Court held that the park’s “whites only” restriction violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Because the park was held in trust by a public entity, the Court ruled that it could not lawfully exclude nonwhite persons, and it rejected an attempt to preserve segregation by transferring the trust to private trustees, reasoning that a public park, by its nature, could not be operated on a racially exclusive basis. A subsequent case, Evans v. Abney (1970), addressed the fate of the trust after segregation was deemed unlawful. The Supreme Court of Georgia concluded that Bacon’s intention to provide a park for whites only had become impossible to fulfill and that the trust therefore failed, causing the parkland and other trust property to revert to Bacon’s heirs under Georgia law. The U.S. Supreme Court affirmed, holding that the refusal to apply the doctrine of cy pres in order to preserve the park on an integrated basis did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment. Bacon’s heirs then sold the property to private developers, who converted the land near North Avenue and Nottingham Drive in Macon to commercial use, leaving his legacy indelibly linked both to his long Senate service and to the legal battles over segregation that followed his death.