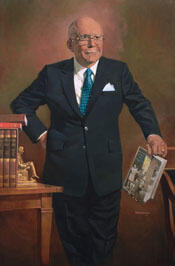

Representative Augustus F. Hawkins

Here you will find contact information for Representative Augustus F. Hawkins, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | Augustus F. Hawkins |

| Position | Representative |

| State | California |

| District | 29 |

| Party | Democratic |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | January 9, 1963 |

| Term End | January 3, 1991 |

| Terms Served | 14 |

| Born | August 31, 1907 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | H000367 |

About Representative Augustus F. Hawkins

Augustus Freeman Hawkins (August 31, 1907 – November 10, 2007) was an American politician of the Democratic Party who served in the California State Assembly from 1935 to 1963 and as a Representative from California in the United States Congress from 1963 to 1991. Over the course of his 58-year elective career, he authored more than 300 state and federal laws, including Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the 1978 Humphrey-Hawkins Full Employment Act. A pioneering African-American legislator and a key figure in mid‑twentieth‑century liberal politics, he was known as the “silent warrior” for his commitment to education, civil rights, and ending unemployment, and was the first Black member of Congress elected from west of the Mississippi River.

Hawkins was born in Shreveport, Louisiana, the youngest of five children of Nyanza Hawkins and Hattie Freeman. An African American of mixed-race ancestry, he was very light-skinned and reportedly resembled his English grandfather; throughout his life he was often assumed to be of solely white ancestry, but he refused to pass as white. In 1918, when he was a boy, his family moved to Los Angeles, California, where he came of age in a growing but politically underrepresented Black community. He graduated from Jefferson High School in Los Angeles in 1926 and went on to the University of California, Los Angeles, receiving a bachelor’s degree in economics in 1931. He had planned to study civil engineering after college, but the financial constraints of the Great Depression made further study impossible. The economic dislocation of the era helped shape his interest in politics and his lifelong devotion to education and employment opportunities.

After graduating from UCLA, Hawkins operated a real-estate company with his brother while studying government and becoming increasingly active in Democratic politics. At a time when most African Americans still identified with the Republican Party, he was part of a broader shift toward the Democrats. He supported Franklin D. Roosevelt’s presidential campaign in 1932 and favored New Deal measures that were popular among working-class and Black voters. In the 1934 California gubernatorial election, he backed Upton Sinclair, a Socialist-turned-Democrat whose controversial campaign further aligned Hawkins with progressive causes. In 1945, while serving in the legislature, Hawkins married Pegga Adeline Smith on August 28; she died in 1966. He later married Elsie Taylor in 1977.

Hawkins entered elective office in 1934, when he defeated 16‑year incumbent Republican Frederick Madison Roberts—the first African American in the California State Assembly and a great-grandson of Sally Hemings and President Thomas Jefferson—for a Los Angeles–area Assembly seat. Taking office in 1935, Hawkins served in the California State Assembly until 1963 and by the time of his departure was its most senior member, as Roberts had been before him. At the time, Black representation in government was extremely limited, and Los Angeles’s Black community had virtually no other elected representation at the city, county, state, or federal level. His district was a mixture of Latinos, African Americans, and working-class white migrants from the South and Midwest, and he used his position to champion fair employment and housing, low‑cost housing, disability insurance, and workers’ compensation protections for domestic workers. Among his early legislative achievements was a fair-housing law that prohibited discrimination by builders receiving federal funds. He served as a delegate to the Democratic National Conventions of 1940, 1944, and 1960 and as a presidential elector from California in 1944. In 1958 he sought the speakership of the Assembly, losing to Ralph M. Brown but gaining the chairmanship of the powerful Rules Committee; had he succeeded, he would have been the first African-American Speaker in California history.

In 1962, following the creation of a new majority-Black congressional district encompassing central Los Angeles, Hawkins ran for the U.S. House of Representatives with the endorsement of President John F. Kennedy. He won both the Democratic primary and the general election easily and took office in January 1963. From 1963 to 1991, he represented California’s 21st District (1963–1975) and 29th District (1975–1991), covering southern Los Angeles County, and was consistently reelected with more than 80 percent of the vote in his heavily Democratic constituency. His service in Congress thus spanned 14 terms during a significant period in American history, including the civil rights era, the Great Society, the Vietnam War, and the conservative turn of the 1980s. As a member of the House of Representatives, Augustus Freeman Hawkins participated actively in the legislative process and represented the interests of his constituents while becoming a central figure in national debates over civil rights, employment, and education policy.

Hawkins quickly emerged as an influential liberal voice in Congress and a strong supporter of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society. Early in his congressional career, he coauthored Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibited employment discrimination and established the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. A staunch advocate of civil rights, he toured the South in 1964 to promote African-American voter registration. Five days after the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was signed into law, the Watts Riots erupted in his district, the first of a series of major urban uprisings in the 1960s. Hawkins condemned the violence but used the crisis to urge his colleagues to increase antipoverty funding and address underlying inequalities, even as the riots contributed to a political backlash against fair-housing and other Great Society initiatives. Because of his light skin and heightened racial tensions, he had to exercise particular caution when visiting his district in the immediate aftermath of the unrest.

On foreign policy, Hawkins initially shared President Johnson’s skepticism about deepening U.S. involvement in Vietnam, arguing that the war threatened to undermine the Great Society and that the United States could not impose its way of life on other nations. As the conflict escalated and South Vietnam’s instability became apparent, he grew more critical. After touring South Vietnam in June 1970, he and Representative William Anderson authored a House resolution condemning the “cruel and inhumane treatment” of prisoners in South Vietnamese facilities. They had visited a civilian prison on Con Son Island, which they likened to “tiger cages,” and pressed President Richard Nixon to send an independent task force to investigate conditions and prevent further abuse. Domestically, Hawkins was a founding member of the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) and served as its first vice chairman from 1971 to 1973, though he preferred to focus on detailed legislative work rather than public confrontation. He criticized what he saw as excessive theatrics in the civil rights movement, contending that there needed to be “clearer thinking and fewer exhibitionists,” and in 1980 he described the CBC as “85 percent social and 15 percent business.” Among his notable achievements was securing the restoration of honorable discharges to 170 Black soldiers of the 25th Infantry Regiment who had been falsely accused in the 1906 Brownsville, Texas, incident and summarily dismissed from the Army.

Hawkins’s legislative record in Congress was extensive and focused heavily on employment, education, and equal opportunity. In addition to Title VII, he played a key role in the passage of the 1974 Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act, which provided protections and alternative approaches for young offenders; the 1978 Comprehensive Employment and Training Act; and the 1978 Pregnancy Disability Act, designed to prevent discrimination against women on the basis of pregnancy. Of the latter, he said that Congress had “the opportunity to ensure that genuine equality in the American labor force is more than an illusion and that pregnancy will no longer be the basis of unfavorable treatment of working women.” He is best known for sponsoring, with Senator Hubert H. Humphrey of Minnesota, the 1978 Humphrey-Hawkins Full Employment Act, which set a national goal of full employment and required the chair of the Federal Reserve Board to report regularly to Congress on the state of the economy. By the time President Jimmy Carter signed it, the act had been significantly weakened and was largely symbolic, but it remained a touchstone for advocates of active federal employment policy. Hawkins later authored landmark measures such as the Job Training Partnership Act and the 1988 School Improvement Act, and in 1984 he became chair of the House Education and Labor Committee, from which he continued to press for expanded educational opportunities and job training programs.

During the 1980s, Hawkins often found himself on the defensive as the administrations of Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush pursued more conservative domestic policies and many Democrats moved toward the political center. He was frustrated by what he viewed as the limited progress possible in that climate and suffered a major setback when President Bush vetoed the Civil Rights Act of 1990, sometimes called the Hawkins-Kennedy Civil Rights Act. The bill would have overturned several recent Supreme Court decisions that had shifted the burden of proof in employment discrimination cases from employers to employees. Bush’s veto, the only successful veto of a civil rights act in United States history, blocked the measure while Hawkins was still in office; a narrower Civil Rights Act of 1991 was enacted after his retirement. Hawkins retired from Congress in January 1991, having never lost an election in his long career, and left office as one of the most senior and influential liberal Democrats in the House.

After retiring from Congress, Hawkins remained in the Washington, D.C., area at the preference of his wife Elsie, residing there until his death. Elsie Taylor Hawkins died in 2007, and he died two months later, on November 10, 2007, at Suburban Hospital in Bethesda, Maryland, at the age of 100. At the time of his death he was the oldest living former member of Congress and the eighth member of Congress to become a centenarian; his passing left former Representative Arthur Glenn Andrews of Alabama as the oldest living former House member. His legacy has been commemorated in several ways in his home state of California and nationally. The Augustus F. Hawkins Nature Park, an 8.5‑acre urban park in southern Los Angeles featuring the Evan Frankel Discovery Center with natural history and environmental exhibits, was completed in 2000 at a cost of $4.5 million, financed largely through city, county, and state bond measures. The Augustus F. Hawkins Centers of Excellence Program, a federal grants initiative, supports diversification of the U.S. teaching force. Augustus F. Hawkins High School in Los Angeles, opened in 2012, also bears his name, reflecting his enduring association with education, opportunity, and public service.