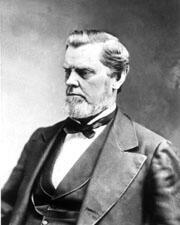

Senator Benjamin Harvey Hill

Here you will find contact information for Senator Benjamin Harvey Hill, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | Benjamin Harvey Hill |

| Position | Senator |

| State | Georgia |

| Party | Democratic |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | December 6, 1875 |

| Term End | March 3, 1883 |

| Terms Served | 2 |

| Born | September 14, 1823 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | H000587 |

About Senator Benjamin Harvey Hill

Benjamin Harvey Hill (September 14, 1823 – August 16, 1882) was a Georgia lawyer and politician whose career spanned the antebellum era, the Civil War, Reconstruction, and the post-Reconstruction “New South.” A member of multiple political parties over his lifetime and ultimately a Democrat, he served in both houses of the Georgia legislature, in the Confederate Provisional Congress and Confederate Senate, and later in the United States House of Representatives and the United States Senate. Known as “the peerless orator,” he became particularly noted for his “flamboyant opposition” to Congressional Reconstruction, an opposition that contemporaries and later observers credited with helping to inaugurate Georgia’s Ku Klux Klan. His famous “brush arbor speech” in Atlanta on July 23, 1868, called for the use of violence against the governor, the legislature, and freed people.

Hill was born on September 14, 1823, in Hillsboro, Jasper County, Georgia, and was of Welsh and Irish American ancestry. He attended the University of Georgia in Athens, where he was a member of the Demosthenian Literary Society and graduated in 1844 with first honors. Later that year he was admitted to the Georgia bar and began the practice of law. In 1845 he married Caroline E. Holt in Athens, Georgia. His early legal and intellectual training, combined with his oratorical skill, quickly propelled him into public life in a state undergoing rapid political and sectional change.

Hill’s political career began in the volatile party environment of the 1850s. He was elected to the Georgia state legislature in 1851 as a member of the Whig Party. As national parties realigned over immigration and slavery, he supported Millard Fillmore on the American (Know-Nothing) Party ticket in 1856 and served as an elector for that party in the Electoral College. In 1857 he ran unsuccessfully for governor of Georgia against the Democratic nominee, Joseph E. Brown. Two years later, in 1859, he was elected to the Georgia state senate as a Unionist, and in 1860 he again served as a presidential elector, this time for John Bell and the Constitutional Union (Unionist) Party. Although initially opposed to secession and elected as a Unionist in 1860, he nonetheless voted to secede that year when Georgia considered leaving the Union.

At the Georgia secession convention on January 16, 1861, Hill was the only non-Democratic member and, alongside Alexander H. Stephens, spoke publicly against immediate dissolution of the Union. While Stephens advanced a conservative constitutional argument, Hill adopted a more pragmatic tone. He warned that disunion could ultimately lead to the abolition of slavery and the downfall of Southern society, quoting Northern abolitionist Henry Ward Beecher to show that some in the North welcomed disunion as a path to ending slavery. Hill characterized the Republican Party as a “disunionist” party in contrast to the “Union men and Southern men” at the convention and urged Georgians to resist Abraham Lincoln’s administration democratically within the bounds of the Constitution, likening this course to the calm and deliberative example of George Washington. At the same time, he counseled that the South should prepare for secession and war if necessary. When Georgia ultimately left the Union, Hill became a political ally of Confederate President Jefferson Davis. He joined the Confederate Provisional Congress and was subsequently elected by the Georgia legislature to the Confederate States Senate, in which he served for the duration of the Confederacy.

Hill’s Confederate service was marked by both influence and controversy. In 1863 he became embroiled in a heated dispute with Alabama Senator William Lowndes Yancey, a critic of President Davis, during debate over a bill to create a Confederate Supreme Court. The confrontation escalated into physical violence when Hill struck Yancey in the head with a glass inkstand, knocking him over a desk and onto the Senate floor. The incident was kept secret for months, and when it was finally investigated, it was Yancey, not Hill, who was censured. Yancey left Congress before adjournment to recover; his health deteriorated rapidly, and he died on July 27, 1863, of kidney disease. At the close of the Civil War, Hill was arrested by Union authorities as a former Confederate official and confined at Fort Lafayette in New York Harbor from May until July 1865.

During Reconstruction, Hill emerged as one of Georgia’s most outspoken opponents of federal policy. In 1867 he published a series of essays in the Augusta Chronicle titled “Notes on the Situation,” which his son later described as filled with “severe and bitter invective” against Congressional Reconstruction and particularly against the political participation of Black voters. His “flamboyant opposition” to Reconstruction and his rhetoric in this period were credited by contemporaries with helping to inaugurate Georgia’s Ku Klux Klan. On July 23, 1868, in Atlanta, he delivered his notorious “brush arbor speech,” in which he called for the use of violence against the Republican governor, the state legislature, and freed people. After Black legislators were ejected from the Georgia House of Representatives and the Ku Klux Klan had frightened away most Black voters, Georgia was readmitted to the Union. On July 31, 1871, in this changed political environment, Hill began to recast himself as a spokesman for what he termed a “New South,” advocating a more conciliatory posture toward the North while maintaining white supremacy at home.

Near the end of the Reconstruction era, Hill returned to national office. In 1874 he was elected as a Democrat to the United States House of Representatives from Georgia and served from May 5, 1875, to March 3, 1877. His service in Congress took place during a significant period in American history, as federal authorities retreated from Reconstruction and Southern Democrats reasserted control over state governments. On January 26, 1877, the Georgia legislature elected Hill to the United States Senate. He took his seat on March 4, 1877, and served as a Senator from Georgia until his death on August 16, 1882. Over the course of his two terms in Congress—first in the House and then in the Senate—Hill participated in the legislative process and represented the interests of his Georgia constituents as a member of the Democratic Party, contributing to debates over the postwar settlement, federal power, and Southern economic development.

Benjamin Harvey Hill died in office on August 16, 1882. His obituary appeared on the front page of the Atlanta Constitution on August 17, 1882, reflecting his prominence in Georgia public life. He is buried in historic Oakland Cemetery in Atlanta, Georgia. His memory was later commemorated in several ways: a life-size statue of Hill, mounted on a similarly sized plinth, was installed inside the Georgia State Capitol in Atlanta, and a larger-than-life portrait of him hangs in the Capitol Rotunda. Ben Hill County, Georgia, created in 1906, was named in his honor. His name also appears among the signers of the Georgia Ordinance of Secession and on lists of members of the United States Congress who died in office between 1790 and 1899.