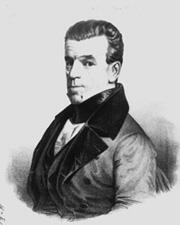

Senator Clement Comer Clay

Here you will find contact information for Senator Clement Comer Clay, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | Clement Comer Clay |

| Position | Senator |

| State | Alabama |

| Party | Democratic |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | December 7, 1829 |

| Term End | December 31, 1841 |

| Terms Served | 4 |

| Born | December 17, 1789 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | C000481 |

About Senator Clement Comer Clay

Clement Comer Clay (December 17, 1789 – September 6, 1866) was an American attorney, judge, and Democratic politician who served Alabama in both houses of the United States Congress and as the eighth governor of the state. He served as a Senator from Alabama in the United States Congress from 1829 to 1841, during a significant period in American history, and contributed to the legislative process during four terms in office. Over the course of his career, he was elected to the Alabama Territorial Legislature, the Alabama House of Representatives, the U.S. House of Representatives, and the United States Senate. He and his son, who also served as a U.S. senator, were among Alabama’s most prominent enslavers; according to the Washington Post and the 1860 census, together they enslaved 87 people on four Alabama plantations.

Clay was born in Halifax County, Virginia, the son of Rebecca (Comer) Clay and William Clay, an officer in the American Revolutionary War. His family later moved west to Grainger County, Tennessee, where he attended local schools. He pursued higher education at East Tennessee College (later the University of Tennessee), from which he graduated in 1807. After reading law, he was admitted to the bar in 1809. In 1811 he moved to Huntsville, in what would become the state of Alabama, where he began a law practice. Clay arrived in Huntsville owning very little money and one enslaved person, marking the beginning of both his legal career and his increasing involvement in the slave-based plantation economy of the region.

Clay’s public career began in the territorial period. He served in the Alabama Territorial Legislature from 1817 to 1818, helping to shape the institutions of the future state. He subsequently held judicial office as a state court judge and served in the Alabama House of Representatives. On April 4, 1815, he married Susannah Claiborne Withers; the couple had three sons: Clement Claiborne Clay, John Withers Clay, and Hugh Lawson Clay. As his legal and political standing grew, so did his investment in slavery. By 1830 he enslaved 52 people, and by 1834 that number had risen to 71, reflecting both his personal wealth and his deepening entanglement in the plantation system.

In 1828 Clay was elected as a Democrat to the U.S. House of Representatives. He took his seat on March 4, 1829, and, through successive re-elections, served until March 3, 1835. During these years in the House he participated in the national legislative debates of the Jacksonian era and represented the interests of his Alabama constituents in Washington. His service in Congress occurred during a period of intense controversy over banking policy, Indian removal, and the expansion of slavery, issues that would continue to shape his later executive and senatorial careers.

Clay left the House when he was elected governor of Alabama in 1835, assuming office as the state’s eighth governor. His gubernatorial term, which lasted from 1835 to 1837, was dominated by the Creek War of 1836, a violent conflict arising from resistance to Indian Removal policies implemented in the Southeast after 1830. Under his administration, and pursuant to the 1832 Treaty of Cusseta, the United States Army removed the Creek Indians from southeastern Alabama to Indian Territory (now Oklahoma), west of the Mississippi River, amid confrontations between Native Americans and white settlers. In 1836, Governor Clay also signed the legislative act chartering Spring Hill College in Mobile, Alabama, a Jesuit institution that became the third-oldest Jesuit college in the United States. The charter granted the college full authority to confer academic degrees in the arts and sciences, reflecting the strong French Catholic traditions of Mobile, originally founded as a French colony.

Clay’s tenure as governor coincided with the onset of the Panic of 1837, a nationwide financial crisis fueled by speculative excesses and instability in the banking system. The panic caused a run on the Bank of the State of Alabama. In response, Clay ordered the bank to provide a detailed financial report, but it was unable to do so, highlighting the fragility of the state’s financial institutions. His term as governor ended early in 1837 when the Alabama legislature, which at that time elected U.S. senators, chose him to represent the state in the United States Senate.

After his election by the state legislature, Clay entered the United States Senate on June 19, 1837. He served there until his resignation on November 15, 1841. As a member of the Senate and the Democratic Party, he participated in the democratic process at the national level and represented Alabama’s interests during a period marked by continuing economic distress after the Panic of 1837, ongoing debates over slavery and territorial expansion, and the evolving party system of the antebellum United States. His combined service in the House and Senate, spanning from 1829 to 1841, placed him at the center of federal policymaking for more than a decade.

In his later years, Clay continued to reside in Alabama and remained a prominent figure in the state’s political and social life. His ownership of enslaved people fluctuated with his financial circumstances; from 1840 to 1850 he sold many of those he enslaved in order to meet his debts, yet by 1860 he again claimed ownership of 84 enslaved people. By that time, he and his son, Senator Clement Claiborne Clay, together enslaved 87 people on four plantations, underscoring the scale of their involvement in and benefit from the institution of slavery. In the year after the end of the Civil War, Clement Comer Clay died of natural causes on September 6, 1866, at the age of 76. His wife Susannah had died earlier that same year. They were both buried at Maple Hill Cemetery in Huntsville, Alabama.