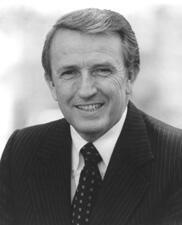

Senator Dale Bumpers

Here you will find contact information for Senator Dale Bumpers, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | Dale Bumpers |

| Position | Senator |

| State | Arkansas |

| Party | Democratic |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | January 14, 1975 |

| Term End | January 3, 1999 |

| Terms Served | 12 |

| Born | August 12, 1925 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | B001057 |

About Senator Dale Bumpers

Dale Leon Bumpers (August 12, 1925 – January 1, 2016) was an American lawyer and Democratic politician who served as the 38th governor of Arkansas from 1971 to 1975 and as a United States Senator from Arkansas from January 3, 1975, to January 3, 1999. Over four terms in the Senate, he contributed to the legislative process during a significant period in American history, participating in the democratic process and representing the interests of his Arkansas constituents. After leaving elective office, he practiced law in Washington, D.C., as counsel at the firm Arent Fox LLP, where his clients included Riceland Foods and the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

Bumpers was born on August 12, 1925, in Charleston, Franklin County, in west-central Arkansas, near Fort Smith. He was the son of William Rufus Bumpers, who served in the Arkansas House of Representatives in the early 1930s, and Lattie Jones Bumpers (1889–1949). He grew up in a close-knit family with two older brothers, Raymond J. Bumpers, who died of dysentery, and Carroll Bumpers, born in 1921, as well as a sister, Margaret. His early life was marked by both the influence of his father’s public service and profound personal tragedy. In March 1949, his parents died within five days of each other from injuries sustained in an automobile accident; they were interred at Nixon Cemetery in Franklin County. These experiences helped shape his sense of responsibility, resilience, and public duty.

Bumpers attended public schools in Charleston and then enrolled at the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville. During World War II, he served in the United States Marine Corps from 1943 to 1946, an experience that exposed him to national service at a young age. After the war, he pursued legal studies and graduated from Northwestern University School of Law in Chicago in 1951. While in Illinois, he became a strong admirer of Adlai Stevenson II, the Democratic presidential nominee in 1952 and 1956, whose style and reform-minded politics influenced Bumpers’s own political outlook. He was admitted to the Arkansas bar in 1952 and returned to his hometown of Charleston to begin practicing law that same year.

From 1952 to 1970, Bumpers served as Charleston’s city attorney while maintaining his private law practice. In that role, he played a pivotal part in school desegregation in Arkansas. After the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education, he persuaded the local school board to comply fully with the ruling. As a result, Charleston became the first school district in the former Confederate South to fully integrate its public schools, an achievement Bumpers regarded as one of his proudest. He also served as a special justice of the Arkansas Supreme Court in 1968. His early political ambitions met with initial disappointment when he lost a 1962 bid for the same Arkansas House of Representatives seat once held by his father, a race that underscored the challenges of entering statewide politics but did not deter his future efforts.

Bumpers emerged on the statewide scene in 1970 when, though virtually unknown outside his region, he announced his candidacy for governor of Arkansas. His oratorical skill, personal charm, and image as an outsider reformer quickly gained traction. He forced a runoff in the Democratic primary against former governor Orval Faubus, whom he defeated, and then went on to defeat incumbent Republican Governor Winthrop Rockefeller in the November general election. Often described as a new kind of Southern Democrat, Bumpers promised to modernize state government and reform the Democratic Party. His victory ushered in an era of youthful, reform-minded Arkansas governors, a pattern continued by two of his successors, David Pryor—who would later serve alongside Bumpers in the U.S. Senate—and future President Bill Clinton.

As governor from 1971 to 1975, Bumpers focused on streamlining and modernizing Arkansas’s state government. His foremost objective, as later described by political analyst Dan Durning, was to reorganize the executive branch by consolidating roughly 60 major agencies into 13 cabinet-level departments, thereby enhancing gubernatorial authority and administrative efficiency. Unlike his Republican predecessor Rockefeller, who had struggled against entrenched special interests, Bumpers successfully pushed this reorganization through the legislature. He advanced a more progressive tax structure by raising the top income tax rate from 5 to 7 percent, significantly increasing state revenues as Arkansas industrialized and wages rose. He opposed regressive sales tax increases and instead used the additional revenue to raise teacher salaries and improve public schools, strengthening his support among educators. His administration also enacted a home rule law for local governments, created a consumer protection division, repealed certain liquor laws, upgraded prison facilities, and, in a 1972 special session, expanded county-level social services for the elderly, the disabled, and the mentally ill. In the 1973 General Assembly, he secured further education reforms, including a state-supported kindergarten program, free textbooks for high school students, increased support for children with disabilities, higher teacher pay and improved retirement benefits, and a major construction program for state colleges and universities, along with support for community colleges through extended state operational funding. Not all of his proposals succeeded—measures such as a $10 million wilderness and scenic lands acquisition program and ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment were rejected—but his overall legislative success reflected strong public backing, a more reform-oriented legislature, his personal powers of persuasion, and his relative independence from special interest groups. He was reelected governor in 1972 and left office in 1975 to enter the U.S. Senate.

In 1974, Bumpers ran for the United States Senate and unseated long-serving Senator J. William Fulbright, chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, in the Democratic primary by a wide margin. In the general election he faced Republican banker John Harris Jones, who criticized Bumpers’s record as governor, particularly the construction of a $186 million state office complex, and accused him of excessive spending. Bumpers largely ignored Jones and devoted considerable campaign energy to supporting young Democrat Bill Clinton in his unsuccessful bid to unseat Republican Representative John Paul Hammerschmidt in Arkansas’s 3rd congressional district. Bumpers won the Senate race overwhelmingly, receiving 461,056 votes (84.9 percent) to Jones’s 82,026 (15.1 percent), the weakest Republican showing in an Arkansas Senate race since Fulbright’s 1944 victory. National media took note of his rise; Time magazine observed that “many to their sorrow have had trouble taking Bumpers seriously … Dandy Dale, the man with one speech, a shoeshine, and a smile,” a characterization that underscored both his charisma and the initial underestimation of his political skills.

Bumpers was reelected to the Senate three times. In 1980, amid Ronald Reagan’s presidential victory in Arkansas, he defeated Republican William P. “Bill” Clark, a Little Rock investment banker, by a margin of 477,905 votes (59.1 percent) to 330,576 (40.9 percent). Clark, who had previously run unsuccessfully for Congress and entered the Senate race only an hour before the filing deadline, attacked Bumpers as “fuzzy on the issues” and criticized his votes against defense appropriations, his support for gasoline rationing during the energy crisis, his opposition to school prayer, and his backing of the Panama Canal Treaties of 1978. Clark also alleged that Bumpers had disparaged residents of Newton County as “stupid hill people,” and he carried that county and eleven others, largely in northwestern Arkansas, including Bumpers’s home county of Franklin. Nonetheless, Bumpers retained broad statewide support. In 1986, he defeated Republican Asa Hutchinson, who would later serve as U.S. Representative and governor of Arkansas. In 1992, after winning the Democratic primary against State Auditor Julia Hughes Jones with 64 percent of the vote, he defeated Republican Mike Huckabee, another future Arkansas governor, in the general election. When Bumpers chose not to seek reelection in 1998, Democrat Blanche Lincoln, a former U.S. Representative from Arkansas’s 1st congressional district, won the seat by defeating Republican state senator Fay Boozman, who later served as Arkansas Department of Health director under Governor Huckabee.

During his Senate tenure from 1975 to 1999, Bumpers became known for his eloquent speaking style, his independence, and his strong reverence for the United States Constitution. He was elected to the Senate four times and served in key leadership roles. From 1987 until 1995, he chaired the Senate Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship, guiding legislation affecting small firms and economic development. After Republicans gained control of the Senate in the 1994 elections, he served as ranking minority member of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee from 1997 until his retirement. He was widely regarded as a constitutional purist and notably never supported any constitutional amendment, reflecting his belief in the durability and sufficiency of the existing document. Although he was encouraged by colleagues, including Senator Paul Simon of Illinois, to seek the Democratic presidential nomination in 1984 and 1988 and was initially mentioned as one of Walter Mondale’s top potential vice-presidential choices in 1984, he declined to run for national office. He later explained that his principal reason was a desire to avoid “a total disruption of the closeness my family has cherished.” Observers also suggested that he lacked the intense personal ambition often associated with presidential candidates and that his 1978 vote helping to defeat labor law reform had alienated organized labor, complicating any national campaign.

After retiring from the Senate in 1999, Bumpers joined the Washington, D.C., office of Arent Fox LLP as counsel, where he represented clients including Riceland Foods and the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. A self-described close friend of President Bill Clinton, he returned to the Senate chamber in a different capacity during Clinton’s impeachment trial. On January 21, 1999, he delivered an impassioned closing argument for the White House defense team, invoking both constitutional history and public sentiment. Quoting H. L. Mencken, he remarked, “When you hear somebody say, ‘This is not about money’ – it’s about money. And when you hear somebody say, ‘This is not about sex’ – it’s about sex.” He argued that Clinton had not committed a “political crime against the state” and urged senators, in honoring their oaths and the history of the impeachment clause, to reject conviction, stating that while they could censure Clinton or refer him for prosecution, “you cannot convict him.” He concluded by noting that “The American people are now and for some time have been asking to be allowed a good night’s sleep. They’re asking for an end to this nightmare. It is a legitimate request.”

Bumpers’s contributions were recognized in his home state and nationally. In 1995, the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville established the Dale Bumpers College of Agricultural, Food and Life Sciences in his honor, reflecting his long-standing interest in rural development, education, and agriculture. In 2014, the White River National Wildlife Refuge in Arkansas was renamed the Dale Bumpers White River National Wildlife Refuge. At the dedication ceremony, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Director Daniel M. Ashe praised Bumpers as “a giant among conservationists and a visionary who followed an unconventional path to set aside some of Arkansas’ last wild places,” noting that it was fitting he would be “forever linked with the White River.” Dale Bumpers died on January 1, 2016, leaving a legacy as a reform-minded governor, influential senator, and respected advocate for education, conservation, and constitutional governance.