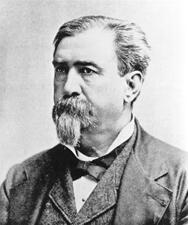

Senator Daniel Wolsey Voorhees

Here you will find contact information for Senator Daniel Wolsey Voorhees, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | Daniel Wolsey Voorhees |

| Position | Senator |

| State | Indiana |

| Party | Democratic |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | July 4, 1861 |

| Term End | March 3, 1897 |

| Terms Served | 9 |

| Born | September 26, 1827 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | V000116 |

About Senator Daniel Wolsey Voorhees

Daniel Wolsey Voorhees (September 26, 1827 – April 10, 1897) was an American lawyer and Democratic politician who represented Indiana in the United States Congress during a transformative era in the nation’s history. A prominent orator known as “the Tall Sycamore of the Wabash,” he served multiple terms in the House of Representatives between 1861 and 1873 and later served as a United States Senator from Indiana from 1877 to 1897. Over the course of his long career, he became a leading figure in the Democratic Party, an anti-war Copperhead during the Civil War, and an influential voice on finance, currency, and Reconstruction policy.

Voorhees was born in Liberty Township, Butler County, Ohio, on September 26, 1827, of Dutch and Scotch-Irish descent. He was the son of Stephen Pieter Voorhees and Rachel Elliott. During his infancy, his parents moved west to Fountain County, Indiana, settling near Covington, where he was raised on the developing frontier of the Old Northwest. This rural, agrarian environment and the political culture of the Wabash Valley deeply shaped his outlook and later political base. He acquired a reputation early in life for unusual height and presence, traits that would later enhance his effectiveness as a courtroom and political speaker.

Voorhees pursued higher education at Indiana Asbury University (now DePauw University) in Greencastle, Indiana, graduating in 1849. After completing his studies, he read law and was admitted to the bar in 1850. He began practicing law in Covington, Indiana, where he quickly distinguished himself as an advocate, especially in jury trials, relying on emotional appeal and vivid rhetoric. In 1857 he moved to Terre Haute, Indiana, which became his long-term home and political base. His legal skill and rising prominence led to his appointment as United States District Attorney for Indiana, a post he held from 1858 to 1861, just as sectional tensions were reaching a crisis.

Voorhees entered national politics as a Democrat in the U.S. House of Representatives, serving from 1861 to 1866 and again from 1869 to 1873. His service in Congress thus began at the outset of the Civil War, a significant period in American history. During the war he emerged as a leading anti-war Democrat, or Copperhead, opposing many of the Lincoln administration’s wartime policies. Although not as radical as Ohio’s Clement Vallandigham, he was accused of membership in the clandestine Knights of the Golden Circle, an organization that promoted Southern expansion and a pro-slavery empire in Central America and the Caribbean. Historian Kenneth Stampp later described Voorhees as embodying the Copperhead spirit, noting his “hot temper, passionate partisanship, and stirring eloquence” and his bitter denunciations of protective tariffs, national banks, and what he viewed as the growing dominance of eastern “Yankee” interests. In the House, he became an ardent defender of states’ rights and personal liberty as he understood them, reflecting the views of many of his western, agrarian constituents.

In the postwar years, Voorhees remained in the House and became a fierce critic of Reconstruction. He was a staunch opponent of Black civil and political rights and repeatedly argued that white Southerners were being oppressed under Reconstruction governments, at times likening their condition to slavery. In his notable “Plunder of the Eleven States” speech, delivered in the House on March 23, 1872, he condemned what he saw as the North’s harsh treatment of the former Confederate states, accusing Congress and the Republican Party of destroying Southern state governments, corrupting the electorate, and subjecting the region to “robberies” and “ruin.” He contended that the liberation of enslaved African Americans had been followed by the effective “enslavement” of white Southerners, a view that placed him firmly among the most outspoken Democratic opponents of Reconstruction policy.

Voorhees’s national influence expanded when he entered the United States Senate, where he served from 1877 to 1897, representing Indiana for two decades and contributing to the legislative process during nine terms in Congress overall. In the Senate he quickly secured a place on the powerful Finance Committee and remained a member throughout his tenure. His first major Senate speech was a defense of the free coinage of silver and a plea for preserving the full legal-tender value of greenback currency, positions that aligned him with agrarian and debtor interests in the Midwest. He became a leading advocate of bimetallism, favoring the use of both silver and gold to back U.S. currency, and he consistently resisted efforts to contract the money supply. On tariff questions he voted reliably with his party for lower duties, though he was candid in acknowledging that any tariff inevitably contained elements of protection, remarking that “the cow and the goose are the greatest fools in the world, except the man who thinks that a tariff can be laid without protection.”

During the 1880s, under Presidents James A. Garfield and Chester A. Arthur, Voorhees joined his fellow Indiana senator, Republican Benjamin Harrison, in promoting closer commercial relations with the United Kingdom. He regarded Britain as a natural trading partner and a vast market for American goods, emphasizing common cultural and political traditions. Within the Senate, he was widely liked on both sides of the aisle despite his fierce partisanship on the stump. He had formed a warm friendship with Abraham Lincoln during their days as circuit-riding lawyers in Indiana and Illinois, a relationship that survived their later political differences. Presidents Ulysses S. Grant and Chester A. Arthur were also said to have enjoyed cordial relations with him, and contemporaries observed that Voorhees sometimes wielded as much influence with Arthur as many Republicans did. He played an active role in securing the construction of the new Library of Congress building, further cementing his reputation as a significant legislative figure.

Voorhees’s Senate career reached a critical juncture in 1893, when President Grover Cleveland called Congress into special session to repeal the silver purchase clause of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act of 1890. As chair of the Senate Finance Committee, Voorhees was in a position to block or delay repeal. Although he remained personally committed to bimetallism and had long championed free silver, political and economic pressures in Indiana had shifted. Industrial and manufacturing interests in his state increasingly demanded adherence to the gold standard, and Democratic members of the Indiana House delegation warned that obstructing repeal would endanger their own political futures. Weighing these factors and aware that he would soon be at odds with Cleveland over tariff reduction, Voorhees chose to carry the repeal bill through the Senate. He refused compromise proposals that would have delayed repeal, and in October 1893 he ensured that unconditional repeal passed, even as many fellow Democrats sought a more gradual approach. In January 1896 he delivered his final major Senate speech, once again defending silver coinage and denouncing tariff protection and the centralization of federal power, a valedictory address delivered as his health declined and as Republican gains in the Indiana legislature made his reelection unlikely.

Throughout his public life, Voorhees was renowned for his oratory and his personal generosity. His height and commanding presence, coupled with a rich, emotional speaking style, made him a compelling figure on the platform and in the courtroom, though critics sometimes noted his carelessness with factual detail. An Indianapolis newspaper once remarked on “the variety and brilliance of his misinformation” and the “unfailing inaccuracy” of some of his historical references. Yet colleagues attested to his kindness and openhandedness. Senator George F. Hoar of Massachusetts, a frequent ideological opponent, described him as “a very kind-hearted man indeed,” always ready to assist colleagues or strangers in distress. Stories circulated of his habit of lending or giving away money so freely that he sometimes lacked enough to pay his own small expenses, prompting a friend in 1894 to observe that Voorhees was “the most unsophisticated person in the use of money” he had ever seen. Fellow senator George Vest of Missouri later quipped that if everyone whom Voorhees had helped brought a single leaf to his grave, he would rest beneath “a mountain of foliage.” His generosity extended to public policy as well; he was notably reluctant to oppose pension bills or other claims on the Treasury when they were advanced by individuals in need.

After his defeat for reelection, Voorhees returned to Indiana and turned to writing and lecturing. He prepared lectures for the lyceum circuit, hoping to supplement his modest finances, and began work on a memoir, “The Public Men of My Times,” which he intended as both a historical record and a potential source of income comparable to the success of Ulysses S. Grant’s memoirs. Only three sections were completed before his health failed. Daniel Wolsey Voorhees died in Washington, D.C., on April 10, 1897, at the age of 69. His long career had spanned the secession crisis, the Civil War, Reconstruction, and the Gilded Age, and he left a complex legacy as a powerful Democratic voice from Indiana, a defender of agrarian and debtor interests, a determined opponent of Reconstruction and Black political rights, and one of the most noted orators of his generation. His personal finances, strained by a lifetime of generosity or profligacy, were so depleted that his estate could not fully cover his funeral expenses, a final testament to the freehanded character that had marked both his private life and his public career.