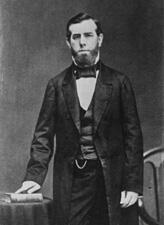

Senator David Colbreth Broderick

Here you will find contact information for Senator David Colbreth Broderick, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | David Colbreth Broderick |

| Position | Senator |

| State | California |

| Party | Democratic |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | December 7, 1857 |

| Term End | December 31, 1859 |

| Terms Served | 1 |

| Born | February 4, 1820 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | B000857 |

About Senator David Colbreth Broderick

David Colbreth Broderick (February 4, 1820 – September 16, 1859) was an American attorney and Democratic politician who served as a United States Senator from California from 1857 until his death in 1859. Elected by the California legislature at a time when senators were not yet chosen by popular vote, he represented the state during a critical pre–Civil War period and became a prominent leader of the Free Soil, anti-slavery wing of the Democratic Party. His career and life were cut short when, at age thirty-nine, he was fatally wounded in a duel with jurist David S. Terry, a former friend, making him the only U.S. Senator ever killed in a duel while in office.

Broderick was born on February 4, 1820, in Washington, D.C., on East Capitol Street just west of 3rd Street. He was the son of an Irish stonecutter who had emigrated to the United States to work on the construction of the United States Capitol, and his wife. In 1823, his family moved to New York City, where he attended public schools. As a boy and young man he was apprenticed to a stonecutter, following his father’s trade. Growing up in New York, he was exposed early to the rough-and-tumble world of urban politics, experiences that would later shape his methods and ambitions as a political organizer.

Broderick became active in Democratic politics as a young man in New York. By the mid-1840s he had emerged as a figure of sufficient prominence to seek national office. In 1846, he was the Democratic candidate for U.S. Representative from New York’s 5th congressional district. In that race he was defeated by Whig candidate Frederick A. Tallmadge, who received 42 percent of the vote to Broderick’s 38 percent, but the campaign helped establish his reputation as a determined and capable political leader. He remained involved in party affairs until the discovery of gold in California and the ensuing Gold Rush drew him west.

Broderick moved from New York to California during the Gold Rush era, joining thousands of other fortune seekers and political aspirants in the rapidly growing state. He soon became deeply involved in California’s Democratic politics and built a powerful urban political organization centered in San Francisco. Broderick was elected to the California State Senate, serving from 1850 to 1852, and he was chosen president of the State Senate from 1851 to 1852. When Lieutenant Governor John McDougall succeeded to the governorship, Broderick, as president of the Senate, served as acting Lieutenant Governor of California from January 9, 1851, to January 8, 1852. During these years he consolidated his influence over San Francisco’s municipal government and Democratic machinery.

From this base, Broderick effectively gained political control of San Francisco. Contemporary observers, including his biographer Jeremiah Lynch, described his rule as “utterly vicious” and associated it with widespread municipal corruption. Broderick adapted techniques he had observed in New York’s Tammany Hall, organizing slates of candidates for lucrative local offices such as sheriff, tax collector, assessor, district attorney, alderman, and legislative seats. These offices often carried no fixed salary but yielded substantial fee income, sometimes exceeding $50,000 per year. Broderick reportedly arranged nominations by promising support in exchange for a share of these proceeds, which he said he needed to maintain and discipline the party organization. In heavily Democratic San Francisco, his chosen candidates were usually victorious, and he became wealthy through this system while solidifying his position as a dominant figure in California’s Democratic Party.

In 1857, Broderick was elected by the California legislature as a United States Senator, and he began his term on March 4, 1857. His service in Congress came during a significant period in American history, just prior to the outbreak of the Civil War, when the Democratic Party in California and nationally was deeply divided over the issue of slavery. As a member of the Senate, Broderick participated in the legislative process, represented the interests of his California constituents, and aligned himself with the Free Soil faction of the Democratic Party, which opposed the extension of slavery into the western territories and into California. Within California, he led the Free Soilers against the pro-slavery wing of the party, a conflict that would have profound personal as well as political consequences.

One of Broderick’s closest associates in California politics was David S. Terry, formerly Chief Justice of the California Supreme Court. Terry, however, was an advocate of extending slavery into California and became a leader of the pro-slavery Democrats. When Terry lost his bid for re-election to the state supreme court, he blamed Broderick and his Free Soil allies for the defeat. The political rivalry between the two men intensified, and Terry, known even among his friends as caustic and aggressive, delivered inflammatory remarks about Broderick at a party convention in Sacramento. Broderick, upon reading the speech, responded with an equally sharp denunciation, calling Terry a “damned miserable wretch” and asserting that he was as corrupt as President James Buchanan and William Gwin, California’s other U.S. Senator. Broderick declared that he had once regarded Terry as the only honest man on a “miserable, corrupt Supreme Court,” but now believed him to be “just as bad as the others.”

This exchange escalated into a challenge to a duel, reflecting the violent political culture of the era. On September 13, 1859, the two former friends, both regarded as expert marksmen, met outside the San Francisco city limits at Lake Merced. The pistols selected for the encounter had hair triggers. As the duel commenced, Broderick’s weapon discharged prematurely, before the final “one-two-three” count, sending his shot harmlessly into the ground and effectively disarming him. Terry then fired and struck Broderick in the right lung. Initially, Terry believed the wound to be only superficial, but it proved fatal. Broderick lingered for three days and died on September 16, 1859, while still serving as a U.S. Senator from California.

Broderick’s death resonated far beyond California. Many contemporaries believed that he had been killed because of his opposition to the expansion of slavery and to what he called a corrupt national administration. At his funeral, held in San Francisco, Edward Dickinson Baker, a close friend of Abraham Lincoln and later a U.S. Senator from Oregon, delivered an oration asserting that Broderick’s death was a “political necessity” disguised as a private quarrel. Baker quoted Broderick’s own words: “I die because I was opposed to a corrupt administration and the extension of slavery.” In the years that followed, some observers came to regard Broderick as a martyr to the anti-slavery cause, and his killing was seen as one episode in the escalating national conflict that led to the Civil War. A portrait of the late senator was displayed at the Republican National Convention in Chicago in May 1860, and another portrait was later hung from the flagstaff of the Hibernian Lincoln and Johnson Club in San Francisco in 1864.

Broderick was originally buried under a monument erected by the State of California in Lone Mountain Cemetery in San Francisco. In 1942, his remains were reinterred at Cypress Lawn Memorial Park in Colma, California. His legacy endured in various place names: Broderick County in the Kansas Territory was named in his honor, as were the former town of Broderick, California, and Broderick Street in San Francisco. The violent end of his long-running feud with David S. Terry also echoed in later history. About thirty years after the duel, Terry himself was shot and killed by Deputy United States Marshal David Neagle while threatening U.S. Supreme Court Justice Stephen Johnson Field, a friend of Broderick. Broderick’s life and death later entered popular culture; in 1963, actor Carroll O’Connor portrayed him in the “Death Valley Days” television episode “A Gun Is Not a Gentleman,” which dramatized his fatal 1859 duel with Terry and its roots in their split over slavery.