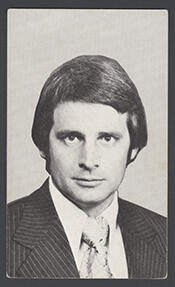

Representative David Alan Stockman

Here you will find contact information for Representative David Alan Stockman, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | David Alan Stockman |

| Position | Representative |

| State | Michigan |

| District | 4 |

| Party | Republican |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | January 4, 1977 |

| Term End | January 3, 1983 |

| Terms Served | 3 |

| Born | November 10, 1946 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | S000935 |

About Representative David Alan Stockman

David Alan Stockman (born November 10, 1946) is an American politician, former businessman, and author who served as a Republican U.S. Representative from Michigan and later as Director of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) under President Ronald Reagan. A member of the Republican Party, he represented Michigan in the United States Congress from January 3, 1977, until his resignation on January 21, 1981, completing three terms in office and contributing to the legislative process during a significant period in American political and economic history.

Stockman was born at Fort Hood, Texas, the son of Allen Stockman, a fruit farmer, and Carol (née Bartz). Of German descent, his family’s surname was originally “Stockmann.” He was raised in a conservative household in St. Joseph, Michigan, where his maternal grandfather, William Bartz, served for 30 years as the Republican treasurer of Berrien County, Michigan. Stockman attended public schools in Stevensville, Michigan, and graduated from Lakeshore High School in 1964. He went on to receive a Bachelor of Arts degree in history from Michigan State University in 1968. That same year he entered Harvard University as a graduate theology student, remaining there until he left the program after 1969.

Stockman began his career in national politics in the early 1970s. From 1970 to 1972, he served as special assistant to United States Representative John Anderson of Illinois, who would later seek the presidency in 1980. He then became executive director of the United States House of Representatives Republican Conference, a position he held from 1972 to 1975. In these roles he gained experience in legislative strategy and party organization, positioning himself as a rising figure within Republican circles in Washington.

In 1976, Stockman was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives from Michigan’s 4th congressional district in Southwest Michigan for the 95th Congress. He took office on January 3, 1977, and was reelected in the two subsequent elections, serving three terms in total. His tenure in the House, which lasted until January 21, 1981, coincided with a period of economic turbulence, including high inflation and unemployment, and intense debate over the size and role of the federal government. As a member of the House of Representatives, David Alan Stockman participated in the democratic process and represented the interests of his constituents while aligning himself with the emerging conservative movement within the Republican Party. His congressional service ended when he resigned to join the incoming Reagan administration.

On January 21, 1981, Stockman was appointed Director of the Office of Management and Budget by President Ronald Reagan, a position he held until his resignation on August 1, 1985. He quickly became one of the most visible and controversial OMB directors in modern history and was widely known as a principal architect and advocate of the administration’s supply-side economic program, often referred to as “Reaganomics.” Stockman played a central role in formulating and securing passage of the “Reagan Budget,” including the Gramm–Latta budget package and the 1981 Kemp–Roth tax cuts, which he later described as a “Trojan horse to bring down the top rate.” He argued that the top marginal tax rate was having a “devastating effect on the economy” and maintained that supply-side tax policy was essentially a “trickle-down” theory, even as he acknowledged the political difficulty of selling it as such. As OMB director, he gained a reputation as a tough negotiator in budget battles with House Speaker Tip O’Neill’s Democratic-controlled House of Representatives and with Majority Leader Howard Baker’s Republican-controlled Senate, as he sought to curtail what he viewed as the “welfare state” and reduce the growth of federal spending.

Stockman’s influence within the Reagan administration was significantly affected by the publication of a lengthy article in The Atlantic Monthly in December 1981, titled “The Education of David Stockman,” based on extensive interviews he had given to journalist William Greider. In the article, Stockman was quoted as saying, “None of us really understands what’s going on with all these numbers,” referring to the budget process, and candidly characterizing the 1981 tax cuts as a vehicle for reducing top tax rates. The article caused a political uproar, and Stockman was famously described as having been “taken to the woodshed” by President Reagan for his remarks. In the years that followed, he became increasingly concerned about the rapid growth of federal deficits and the national debt, especially as the gross federal debt rose from approximately $998 billion on September 30, 1981 (up from $907.7 billion at the end of President Jimmy Carter’s last full fiscal year), to about $1.8 trillion by September 30, 1985, and to $2.1 trillion by the end of fiscal year 1986, following budget negotiations in which he had been deeply involved. In 1981, in recognition of his public service, Stockman received the Samuel S. Beard Award for Greatest Public Service by an Individual 35 Years or Under, one of the Jefferson Awards for Public Service.

After resigning from OMB on August 1, 1985, Stockman turned to Wall Street and private equity. He joined the investment bank Salomon Brothers and later became a partner at the New York–based private equity firm the Blackstone Group. His investment record at Blackstone was mixed, including notable successes such as American Axle alongside less successful ventures such as Haynes International and Republic Technologies. In 1999, after Blackstone CEO Stephen A. Schwarzman curtailed his role in managing certain investments, Stockman left the firm to establish his own private equity company, Heartland Industrial Partners, L.P., based in Greenwich, Connecticut. On the strength of his prior investment record, he and his partners raised approximately $1.3 billion in equity from institutional and other investors. Heartland pursued a contrarian strategy, acquiring controlling interests in companies in sectors attracting relatively little new equity capital, particularly auto parts and textiles. With the assistance of roughly $9 billion in Wall Street debt financing, Heartland completed more than 20 transactions in less than two years, creating four major portfolio companies: Springs Industries, Metaldyne, Collins & Aikman, and TriMas. Several of these investments later performed poorly; Collins & Aikman ultimately filed for bankruptcy in 2005, and Heartland lost most of the $340 million of equity it had invested in Metaldyne when that company was sold to Asahi Tec Corp. in 2006.

In August 2003, Stockman became chief executive officer of Collins & Aikman Corporation, a Detroit-based manufacturer of automotive interior components and a key Heartland portfolio company. His tenure coincided with severe pressures in the automotive supply sector, and he was removed from the position just days before Collins & Aikman filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection on May 17, 2005. On March 26, 2007, federal prosecutors in Manhattan indicted Stockman in connection with what they described as a scheme to defraud Collins & Aikman’s investors, banks, and creditors by manipulating the company’s reported revenues and earnings. The United States Securities and Exchange Commission also brought civil charges against him related to his actions as CEO. Stockman, who personally lost more than $13 million in the collapse alongside losses suffered by as many as 15,000 Collins & Aikman employees worldwide, maintained that the company’s failure was the result of a broad industry decline rather than fraud. On January 9, 2009, the U.S. Attorney’s Office announced that it would discontinue prosecution of the case.

In his later years, Stockman has been active as an author, commentator, and critic of both fiscal and foreign policy. His memoir of the Reagan years, The Triumph of Politics: Why the Reagan Revolution Failed, argued that congressional Republicans had not matched tax reductions with sufficient spending cuts, thereby contributing to large deficits and a rising national debt. He has frequently criticized what he views as the Republican Party’s abandonment of its traditional role as guardian of fiscal discipline, describing it as being on an “anti-tax jihad” that benefits “the prosperous classes.” He has advocated means-testing for Social Security and Medicare and has called for allowing the Bush-era tax cuts to expire and for taxing capital gains at the same rate as ordinary income. He has also been sharply critical of what he calls the “modern imperialists” who, in his view, hijacked the Republican Party during the Reagan era, arguing that the party’s support for an expansive “war machine of invasion and occupation” undermines its ability to restrain federal spending. In economic commentary, he has expressed deep skepticism about central bank policies, remarking that he prefers to invest in “anything that [Federal Reserve Chairman Ben] Bernanke can’t destroy, including gold, canned beans, bottled water and flashlight batteries.”

Stockman resides on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. He is married to Jennifer Blei Stockman, with whom he has two daughters, Rachel and Victoria. Jennifer Blei Stockman is chairwoman emerita of the Republican Majority for Choice and serves as president of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation Board of Trustees. Reflecting an evolution in some of his social views, in 2013 he signed an amicus brief submitted to the Supreme Court in support of same-sex marriage. In 2018, he publicly criticized U.S. interventionist foreign policy, consistent with his broader skepticism of expansive government commitments abroad. He has also served on the board of directors of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, continuing his long-standing engagement with issues of fiscal policy and federal budgeting.