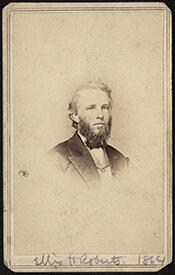

Representative Ellis Henry Roberts

Here you will find contact information for Representative Ellis Henry Roberts, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | Ellis Henry Roberts |

| Position | Representative |

| State | New York |

| District | 22 |

| Party | Republican |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | March 4, 1871 |

| Term End | March 3, 1875 |

| Terms Served | 2 |

| Born | September 30, 1827 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | R000310 |

About Representative Ellis Henry Roberts

Ellis Henry Roberts (September 30, 1827 – January 8, 1918) was an American politician, journalist, and banker who served as a Representative from New York and as the 20th Treasurer of the United States. He was born in Utica, Oneida County, New York, on September 30, 1827, to a family of modest means, and was raised in the public and common schools of the region. He attended Whitestown Seminary in nearby Whitestown, New York, where he prepared for college, and then entered Yale College. At Yale he distinguished himself academically and socially, becoming a member of the Alpha Delta Phi fraternity and the secret society Skull and Bones. He graduated in 1850, part of a generation of Yale-educated New Yorkers who would move into journalism, politics, and public administration in the mid-nineteenth century.

Immediately after his graduation, Roberts returned to Utica and embarked on a career in education. In 1850 and 1851 he served as principal of the Utica Free Academy, a leading secondary school in the city, where he was responsible for instruction and administration at a time when public education in New York was expanding and becoming more systematized. His interest soon shifted from the classroom to the press, and in 1851 he became editor and proprietor of the Utica Morning Herald. Under his leadership, the paper became an influential Republican and reform-oriented journal in central New York. Roberts retained his connection with the Utica Morning Herald for nearly four decades, from 1851 to 1889, using its pages to comment on state and national politics, economic policy, and the emerging issues of the Civil War and Reconstruction eras.

Roberts’s prominence as a journalist and party advocate brought him into active Republican politics. He was a delegate to the Republican National Conventions in 1864, 1868, and 1876, participating in the nomination of Abraham Lincoln’s successor during the Civil War and in the postwar contests that shaped Reconstruction and the party’s national leadership. In New York state politics, he served as a member of the New York State Assembly from Oneida County’s 2nd District in 1867, aligning himself with the Republican majority that supported Union policies and postwar constitutional amendments. Through these roles he gained a reputation as an articulate spokesman for Republican economic and protective-tariff policies, as well as for a strong national government.

In 1870 Roberts was elected as a Republican to the Forty-second Congress, representing New York, and he was reelected to the Forty-third Congress, serving from March 4, 1871, to March 3, 1875. During his two terms in the House of Representatives he sat in a period marked by debates over Reconstruction, civil service reform, and the nation’s financial system in the aftermath of the Civil War. Although specific committee assignments and legislative initiatives are less prominently recorded than his later financial work, he was identified with the party’s protectionist and nationalist economic program. In 1874 he was an unsuccessful candidate for reelection to the Forty-fourth Congress, losing in a Democratic resurgence during the economic difficulties following the Panic of 1873. After leaving Congress in March 1875, Roberts resumed his former newspaper activities in Utica, returning to the Utica Morning Herald and continuing to shape public opinion in upstate New York.

Roberts’s long engagement with economic and fiscal questions, both in Congress and in journalism, led naturally to service in federal financial administration. In 1889 he was appointed Assistant Treasurer of the United States, a post he held until 1893. In that capacity he was involved in the management of federal receipts and disbursements at a time of debate over the gold standard, silver coinage, and tariff policy. After leaving the assistant treasurership, Roberts entered private finance as president of the Franklin National Bank of New York City, serving from 1893 to 1897. His leadership of the bank during the financial instability of the 1890s further solidified his reputation as a careful and experienced financial administrator.

On July 1, 1897, President William McKinley appointed Roberts Treasurer of the United States, making him the nation’s 20th Treasurer. He held this office until June 30, 1905, when he resigned. As Treasurer he oversaw the custody and disbursement of federal funds, the issuance and redemption of currency, and the practical operations of the Treasury during a period that included the Spanish–American War, the subsequent expansion of American overseas commitments, and the economic growth of the early twentieth century. His tenure coincided with continued adherence to the gold standard and the consolidation of the federal government’s role in national finance. After stepping down in 1905, Roberts again engaged in banking and financial pursuits, drawing on his long experience in both public and private sectors.

Beyond his formal offices, Roberts was a prolific writer and advocate of protectionist economic theory. In his work “Government Revenue, Especially the American System. An Argument for Industrial Freedom,” he vindicated the policy of favoring developing domestic commerce over foreign commerce, which he believed protectionism best served. He was a member of the American Protective Tariff League and argued that the tariff had been one of the main reasons why American production had been augmented. In his view, when the United States had low duties approximating free trade, its industries were “battered and depressed,” whereas they thrived when protectionism was the national policy. He regarded the “precious home market” for home trade as monumental and warned that, were the nation to invite foreign commerce at the expense of domestic industry, the home market would be sacrificed and national sovereignty placed in peril. For strategic purposes, he believed, the government should favor producers rather than those who merely exploit trade in all laws that it makes.

Roberts maintained that the most benevolent act of public policy was not to favor foreign commerce in the manner “that trade likes most,” but to foster a broad diversity of employments and domestic production. He argued that a legislator who sought to have his nation engage in commerce without developing a diversity of employments committed a grave error. Rather than decreasing production, he contended, the United States ought to create a more fully developed manufacturing sector and an excellent diversity of employments. He concluded that poverty diminished in direct ratio to the increase in the diversity of industries within the population. For Roberts, one of civilization’s greatest lessons was that the livelihood of all, especially the poor, had been elevated by the erection of new industries and the consequent augmentation of production and employment. With a policy of fostering the growth and diversity of employments, he believed, the United States possessed a promising future, and it would be an egregious injustice for the federal government to contract the scale of production or to adopt a revenue system that heavily courted foreign trade instead of facilitating a diversity of employments for the home market.

In economic philosophy Roberts aligned himself with the Hamiltonian tradition and explicitly rejected the prescriptions of Adam Smith, Jean-Baptiste Say, and American free-trade advocates such as Professor William Graham Sumner, who, in his view, would have organized the American economy primarily around agriculture and left the nation economically dependent on other countries. He praised Alexander Hamilton’s celebrated “Report on Manufactures,” emphasizing Hamilton’s belief that relying on foreign commerce by mainly exporting agricultural goods was wasteful and that America’s agriculture found its best market at home. Roberts highlighted Hamilton’s support for the government’s right to stimulate and foster knowledge, manufactures, agriculture, and commerce, and his advocacy of duties on imports as a strategic means to elevate manufacturing. He endorsed Hamilton’s view that bounties, premiums, and the duty-free importation of certain raw materials, along with rewards to inventors, were worthwhile policies to create a constant domestic clientele for agricultural commodities and to secure the nation’s economic future.

Roberts contrasted what he saw as the British model of economic development, based on foreign commerce and dependence on foreign consumption, with the American model, which he believed relied on domestic consumption and a robust home market that had become the envy of nations engaged in foreign trade. He insisted that the United States should not forsake its home trade to imitate Britain. Summarizing his view of American commercial policy, he declared, “We want no commerce which we do not win on the field of fair competition. We refuse to maintain a costly navy to force our commodities on unwilling peoples. We have always declined every suggestion to conduct our diplomacy in the interest of foreign trade, except as it is welcomed by the peoples whom we go to seek. The course which we are pursuing has never before been pursued by any great nation, the story of commerce has been a story of violence and grasping greed. The wars of the world have been in large part incited by the purpose to extort treasure and commodities, and to thrust the products of the aggressive power upon reluctant peoples.” This statement encapsulated his belief that a strong, diversified domestic economy and a restrained, non-coercive foreign policy were mutually reinforcing pillars of American national strength.

Ellis Henry Roberts spent his later years in New York, remaining active in financial and intellectual circles and retaining an interest in public affairs and economic policy. He died in Utica, New York, on January 8, 1918, closing a career that had spanned education, journalism, state and national politics, federal financial administration, and banking. He was interred in Forest Hill Cemetery in Utica, the city of his birth and the center of much of his professional and public life.