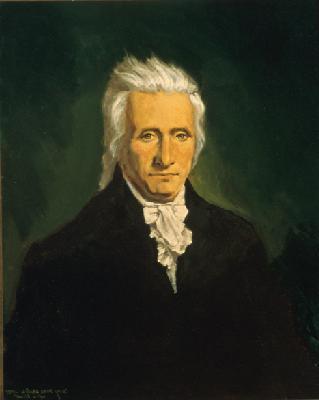

Representative Gabriel Duvall

Here you will find contact information for Representative Gabriel Duvall, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | Gabriel Duvall |

| Position | Representative |

| State | Maryland |

| District | 2 |

| Party | Republican |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | December 2, 1793 |

| Term End | March 3, 1797 |

| Terms Served | 2 |

| Born | December 6, 1752 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | D000578 |

About Representative Gabriel Duvall

Gabriel Duvall (December 6, 1752 – March 6, 1844) was an American politician and jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1811 to 1835, during the tenure of Chief Justice John Marshall. He previously held a series of important state and federal posts, including Comptroller of the Treasury, Chief Justice of the Maryland General Court, member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Maryland, and member of the Maryland House of Delegates. Born in Prince George’s County in the Province of Maryland, he was the sixth child of Benjamin Duvall (1719–1801) and Susanna Tyler (1718–1794), both descendants of the French Huguenot immigrant Mareen Duvall. He was born and raised on family land that would eventually become known as Marietta, a tobacco plantation that remained associated with the Duvall family for generations. Two of his elder brothers died in the American Revolutionary War, a conflict in which he himself later served.

Duvall’s early public career began amid the Revolutionary crisis. He served as a clerk for the Maryland Council of Safety, which managed the state militia, from 1775 to 1777, and then as clerk of the Maryland House of Delegates from 1777 to 1781. In 1776 he served in the American Revolutionary War, first as a mustermaster and commissary of stores, and then as a private in the Maryland militia. He saw action at the Battle of Brandywine and served in Morristown, New Jersey. After his clerical service, he was appointed a commissioner to preserve confiscated British property from 1781 to 1782, and then served on Maryland’s Governor’s Council from 1782 to 1785, participating in the administration of the new state government during the closing years of the war and the early national period.

Duvall read law and was admitted to the bar in Prince George’s County in 1778. He practiced law in Anne Arundel and Prince George’s Counties at least part-time until 1823. In Annapolis he became an active practitioner in the Mayor’s Court as county prosecutor beginning in 1781, and in the Anne Arundel County court beginning in 1783. Archival research indicates that he formally appeared in some 600 cases by 1792, reflecting a substantial regional practice. Over the course of his legal career, he developed a notable specialty in freedom suits. As an attorney, he represented more than 120 enslaved men, women, and children who sued in court for their freedom, reportedly winning nearly 75 percent of those petitions. At the same time, he was himself a substantial enslaver at Marietta, where the Duvall family held between nine and forty people in bondage between 1783 and 1864, including multiple generations of the Duckett, Butler, Jackson, and Brown families. In a striking paradox, Duvall opposed the petition for freedom filed by Thomas and Sarah Butler, members of a family he enslaved at Marietta between 1805 and 1831.

Duvall entered elective politics in the late 1780s. He was elected to the Maryland House of Delegates, serving from 1787 to 1794, during which he participated in the legislative life of the new state under the federal Constitution. He then moved to the national stage. Elected as a U.S. Representative from Maryland’s second district, he served one term in the Fourth Congress from November 11, 1794, to March 28, 1796. After resigning from Congress, he returned to judicial service in Maryland, becoming Chief Justice of the Maryland General Court in 1796, a position he held until 1802. In that role he presided over one of the state’s principal courts at a time when American common law and state judicial institutions were still taking shape.

In 1802, President Thomas Jefferson appointed Duvall as the first Comptroller of the Treasury of the United States, a newly organized post in the federal financial administration. He served as Comptroller from 1802 to 1811, overseeing the examination and settlement of public accounts and gaining extensive experience with federal fiscal law and public debts. This expertise later informed several of his Supreme Court opinions concerning obligations owed to the United States. While serving in federal office, Duvall continued to be associated with the Marietta plantation in Prince George’s County, where his family’s enslaved labor produced tobacco and other crops for the regional market.

On November 15, 1811, President James Madison nominated Gabriel Duvall to an associate justice seat on the Supreme Court of the United States vacated by fellow Marylander Samuel Chase. The United States Senate confirmed him on November 18, 1811, and he received his commission the same day. He was sworn into office on November 23, 1811, and remained on the Court until January 14, 1835, retiring shortly after his eighty-second birthday. During his 23–24 years on the Supreme Court, Duvall sat throughout the Marshall Court era, when the Court was largely a vehicle for Chief Justice John Marshall’s vision of a strong federal government and Marshall himself wrote the great majority of opinions. Duvall authored opinions in only 18 cases—15 majority opinions, two concurrences, and one dissent—an output that later led some scholars to characterize him as one of the least influential justices in the Court’s history.

The question of Duvall’s significance as a justice has been the subject of academic debate. In 1983, University of Chicago law professor David P. Currie argued that “impartial examination of Duvall’s performance reveals to even the uninitiated observer that he achieved an enviable standard of insignificance against which all other justices must be measured.” Currie’s colleague, Frank H. Easterbrook (later a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit), responded that Currie had failed to give “serious consideration of candidates so shrouded in obscurity that they escaped proper attention even in a contest of insignificance,” and concluded that Duvall’s colleague Justice Thomas Todd was even more insignificant. Other commentators have focused on Duvall’s advanced age and alleged infirmities in his later years on the Court. One biographer of Chief Justice Marshall wrote that Duvall “became distinguished for holding on to his seat for many years after he had become aged and infirm because he was fearful of who would replace him,” and Irving Lee Dilliard, Duvall’s biographer, stated that in his last few years on the Court he was “so deaf as to be unable to participate in conversation.” Currie, however, contended that “there is no proof … that Duvall was either deaf or unable to speak while on the Court.”

Despite his limited written output, Duvall’s opinions covered a range of important legal subjects. His sole dissent, in Mima Queen and Child v. Hepburn (1813), arose from a petition for freedom in which the Court considered whether the daughter of a formerly enslaved woman could introduce hearsay evidence that her mother was free at the time of her birth. The Court rejected the hearsay and denied the Queens their freedom. Duvall, as the lone dissenter, argued that the evidence should be admitted, writing that “people of color from their helpless condition under the uncontrolled authority of a master, are entitled to all reasonable protection,” and declaring that “it will be universally admitted that the right to freedom is more important than the right of property.” Among his 15 majority opinions, Freeland v. Heron, Lenox & Co. (1812) addressed commercial law and enforced an English choice-of-law clause, adopting a rule of merchants that a stated account kept without objection for two years bound the party who remained silent. In United States v. January (1813) and Prince v. Bartlett (1814), he developed federal bankruptcy principles; according to Professor John Paul Jones, January made him the “architect of the federal rule” limiting how payments could be applied among competing obligations with different sureties, a doctrine Chief Justice John Roberts later jokingly referred to as “the Duvall rule,” while Prince v. Bartlett has continued to be cited for its distinction between bankruptcy and mere insolvency.

Several of Duvall’s opinions drew directly on his experience as Comptroller of the Treasury. In United States v. Patterson (1813), Walton v. United States (1824), and Parker v. United States (1828), he addressed debts owed to the federal government, holding in Patterson that a debtor could not claim credit until money was in the hands of an authorized public officer, and in Walton that an official bond was a collateral security that did not extinguish the underlying simple contract debt. Parker upheld the government’s right to recoup unauthorized double rations paid to a military officer. In Crowell v. McFadon (1814), United States v. Tenbroek (1817), The Neptune (1818), and The Frances & Eliza (1823), he interpreted federal customs and navigation laws, reversing a state-court judgment against a customs collector enforcing the Embargo Act of 1807, upholding forfeiture of an unregistered vessel, and clarifying the reach of the Navigation Act of 1818. Tenbroek, effectively an advisory opinion given at the Attorney General’s request, was dismissed as improperly before the Court but nonetheless articulated a rule of statutory construction. In land and property law, Boyd’s Lessee v. Graves (1819) held that an agreement on a survey line was not a contract within the statute of frauds, and Piles v. Bouldin (1826) held that interpretation of land grants was for the judge rather than the jury and enforced the statute of limitations. In Rhea v. Rhenner (1828), Nicholls v. Hodges (1828), and Le Grand v. Darnall (1829), he interpreted Maryland law, ruling on the contractual capacity of a married woman abandoned but not legally free to remarry, the status of an executor’s claim against an estate, and the presumption of manumission where a slave owner permitted former slaves and their descendants to own property and contract debts near his residence.

Duvall’s personal life reflected both the religious and social patterns of his region and era. He was an Anglican who, after the American Revolutionary War, became an Episcopalian, maintaining pews at St. Anne’s Church in Annapolis and at his family’s longstanding parish, Holy Trinity Episcopal Church, Collington, originally Henderson’s Chapel of St. Barnabas’ Episcopal Church, Leeland, in Prince George’s County. He married twice. His first marriage, in 1787, was to Mary Bryce (d. 1791), daughter of Annapolis sea captain Robert Bryce; they had one son, Edmund Bryce Duvall (1790–1831). After Mary’s death, Duvall met his second wife, Jane Gibbon (1757–1834), in Philadelphia, where she worked in the boarding house run by her widowed mother, Mary Gibbon. Duvall and other members of Congress lodged there during his federal service in Philadelphia. He and Jane were married on May 5, 1795, at Christ Church in Philadelphia. Mary Gibbon later lived with them at their Washington-area residence during her final years; she died in 1810 and was buried in the Duvall family cemetery at WigWam, part of the Marietta plantation. Questions about the spelling of Duvall’s name persisted among contemporaries and later writers. Early family usage included “DuVal” or “Duval,” and Chief Justice Marshall’s biographer Albert Beveridge preferred “Duval,” but Supreme Court Reporters Cranch, Wheaton, and Peters uniformly used “Duvall,” and journalist and Court specialist Irving Lee Dilliard concluded that the double-“l” spelling had become standard before the future justice’s birth, even though some later family members reverted to “DuVal.”

Gabriel Duvall retired from the Supreme Court on January 14, 1835, and spent his final years at Marietta in Prince George’s County. His second wife, Jane, died there in 1834, and he followed on March 6, 1844, at the age of 91. Both were buried on the family plantation that had been the center of his life from birth, through his long public career in Maryland and the federal government, and into his retirement.