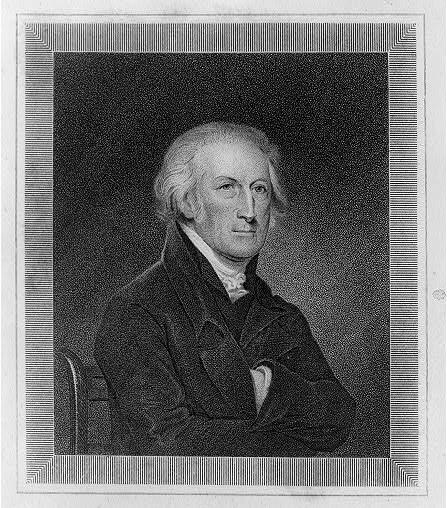

Representative George Clymer

Here you will find contact information for Representative George Clymer, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | George Clymer |

| Position | Representative |

| State | Pennsylvania |

| District | -1 |

| Party | Unknown |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | March 4, 1789 |

| Term End | March 3, 1791 |

| Terms Served | 1 |

| Born | March 16, 1739 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | C000538 |

About Representative George Clymer

George Clymer (March 16, 1739 – January 23, 1813) was an American politician, abolitionist, merchant, and Founding Father of the United States, and was one of only six founders to sign both the Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution. Born in Philadelphia in the Province of Pennsylvania, he was orphaned at about one year of age and was apprenticed to his maternal aunt and uncle, Hannah and William Coleman, who prepared him for a career as a merchant. His early exposure to commerce and public affairs in Philadelphia helped shape his later prominence in revolutionary politics and national finance.

Clymer married Elizabeth Meredith on March 22, 1765. In a letter to the rector of Christ Church, the Reverend Richard Peters, he indicated that he had previously fathered a child, though neither the child’s nor the mother’s name is known. George and Elizabeth Meredith Clymer had nine children, four of whom died in infancy. Their oldest surviving son, Henry, born in 1767, married Philadelphia socialite Mary Willing in 1794. Other children who survived to adulthood included John Meredith, Margaret, George, and Ann, though John Meredith Clymer was killed in the Whiskey Rebellion in 1787 at the age of eighteen. Through his family connections and mercantile activity, Clymer became part of Philadelphia’s commercial and social elite.

From an early stage in the imperial crisis, Clymer emerged as a committed patriot and one of the earliest advocates of complete independence from Britain. He was a leader in the Philadelphia demonstrations against the Stamp Act and the Tea Act, and in 1759 he was inducted as a member of the original American Philosophical Society, reflecting his engagement with the intellectual life of the colonies. He accepted command as a leader of a volunteer corps attached to General John Cadwalader’s brigade. By 1773 he was a member of the Philadelphia Committee of Safety, and in 1776 he was elected to the Continental Congress, where he served until 1780. During his first term in Congress he shared the responsibilities of treasurer of the Continental Congress with Michael Hillegas, served on several important committees, and in the fall of 1776 was sent with Sampson Mathews to inspect the northern army at Fort Ticonderoga on behalf of Congress. When Congress fled Philadelphia in the face of General Sir Henry Clinton’s threatened occupation, Clymer remained in the city with George Walton and Robert Morris to attend to congressional business and financial matters.

Clymer’s business ventures during and after the Revolutionary War increased his personal wealth. In 1779 and 1780 he and his son Meredith engaged in a lucrative trade with the Dutch island of Sint Eustatius. Although he was not personally fond of the merchant business, he continued in partnership with his father‑in‑law and brother‑in‑law until 1782. He resigned from the Continental Congress in 1777 and, turning to state politics, was elected to the Pennsylvania Legislature in 1780. In 1782 he was sent on a tour of the southern states in an unsuccessful effort to persuade state legislatures to honor their financial subscriptions to the central government. He was re‑elected to the Pennsylvania legislature in 1784 and, as his national reputation grew, was chosen as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention in 1787, where he became a Framer of the Constitution.

Clymer’s role at the Constitutional Convention was marked by his opposition to the slave trade and his broader concern with the institution of slavery. He was a member of the Pennsylvania delegation that unsuccessfully sought to regulate the importation of slaves and served on the committee that drafted a compromise postponing any federal prohibition of the slave trade until 1808. He supported the imposition of an export tax, or tariff, as an indirect means of taxing slavery, a measure strongly resisted by southern delegates but ultimately included in the constitutional framework. Although Clymer is known to have been a slave owner, the extent of his ownership is uncertain. His father, grandfather, and brother were minor slave owners, and when his father Christopher died, the seven‑year‑old George inherited “a negro man named Ned,” who died soon afterward. Clymer is generally described as an abolitionist in his later public life, even as his personal history reflected the complexities and contradictions of slavery in the founding generation.

With the establishment of the new federal government, Clymer continued his national service. He was elected as a Representative from Pennsylvania to the First United States Congress and served in the House of Representatives from 1789 to 1791, completing one term in office. A member of what would later be associated with the emerging pro‑administration, or Federalist, interest—though his party is listed as unknown in some records—Clymer contributed to the legislative process during a formative period in American constitutional government. In Congress he participated in debates over the financial and institutional foundations of the new republic and represented the interests of his Pennsylvania constituents as the federal system took shape under President George Washington.

After leaving the House of Representatives in 1791, Clymer remained active in public and civic affairs. When Congress that year passed a bill imposing a duty on spirits distilled in the United States, he was appointed head of the federal excise department in Pennsylvania, a position that placed him at the center of the controversy that culminated in the Whiskey Rebellion. He also served as one of the commissioners appointed to negotiate a treaty with the Creek Indian confederacy, participating in the talks at Colerain, Georgia, on June 29, 1796. In the sphere of finance and culture, Clymer became the first president of The Philadelphia Bank and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and served as vice president of the Philadelphia Agricultural Society, underscoring his influence in banking, the arts, and agricultural improvement.

In his later years, Clymer was regarded as a benefactor and namesake in several communities. He donated the land for the county seat of Indiana County, Pennsylvania, leading to the development of Indiana Borough and earning recognition as its benefactor. The borough of Clymer in Indiana County, Pennsylvania, and the town of Clymer, New York, were named in his honor, as were Clymer Avenue in Indiana, Pennsylvania, Clymer Street in Reading, Pennsylvania, and Clymer Lane in the Leedom Estates section of Ridley Township, Pennsylvania. In Philadelphia, George Clymer Elementary School bears his name. His home in Morrisville, Pennsylvania, known as Summerseat, still stands, as does Ridgeland Mansion, a house he owned in what is now Fairmount Park. The attack transport USS George Clymer (APA‑27) was later named in his honor.

George Clymer died on January 23, 1813, and was buried in the Friends Burying Ground in Trenton, New Jersey. Remembered as a signer of both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, a long‑serving public official, and an early advocate of American independence who grappled with the moral and political challenges of slavery, he remained engaged in political and civic life until the end of his life.