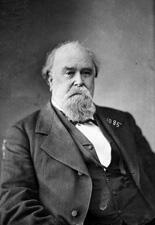

Senator George Smith Houston

Here you will find contact information for Senator George Smith Houston, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | George Smith Houston |

| Position | Senator |

| State | Alabama |

| Party | Democratic |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | May 31, 1841 |

| Term End | December 31, 1879 |

| Terms Served | 10 |

| Born | January 17, 1811 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | H000822 |

About Senator George Smith Houston

George Smith Houston (January 17, 1811 – December 31, 1879) was an American Democratic politician who served Alabama for many years as a state legislator, United States congressman, United States senator, and as the 24th governor of Alabama from 1874 to 1878. A member of the Democratic Party, he contributed to the legislative process over a long national career that included service in both houses of Congress during a significant period in American history. Although one existing account incorrectly states that he served as a senator from 1841 to 1879 for ten terms, Houston in fact served multiple nonconsecutive terms in the United States House of Representatives beginning in the 1840s and was finally elected to the United States Senate in 1878, holding that office until his death in 1879.

Houston was born near Franklin, Williamson County, Tennessee, on January 17, 1811, to David Ross Houston and Hannah Pugh Reagan. He was the paternal grandson of Scots-Irish immigrants. When he was about sixteen years old, his family moved to northern Alabama and settled near Florence, in Lauderdale County. There he worked on the family farm while preparing for a legal career. He read law in the office of Judge George Coalter in Florence and later pursued more formal legal study at a law school in Harrodsburg, Kentucky, completing his preparation for the bar before returning to Alabama.

After his legal training, Houston established himself in Florence and entered public life at an early age. In 1831 he was elected to the Alabama House of Representatives as a Jacksonian Democrat, representing Lauderdale County. Three years later, in 1834, Governor John Gayle appointed him district solicitor, though he was defeated when he stood for election to that office. Houston then moved east to Limestone County, Alabama, where he continued to practice law. In 1837 he was elected in his own right as a solicitor and held that prosecutorial office until 1841, building a reputation as a capable lawyer and Democratic party leader in the Tennessee Valley region.

Houston’s national career began when he was elected as a Democrat to the United States House of Representatives in 1840. During his long tenure in the House, he became one of the chamber’s more influential Southern Democrats. He chaired the House Committee on Military Affairs, the powerful House Committee on Ways and Means, and the House Judiciary Committee at various points in his service. A Southern Unionist in the increasingly sectional atmosphere of the late 1840s, he was one of only four southern Democrats who refused to sign Senator John C. Calhoun’s “Address of the Southern Delegates in Congress to their Constituents” in 1849, which challenged the federal government’s authority to limit slavery in the territories acquired after the Mexican–American War. His refusal to endorse the address contributed to growing opposition among pro-secession elements in Alabama, and he did not seek reelection in 1848. Houston returned to the House after winning election again in 1850, and he remained a significant Democratic voice from Alabama throughout the 1850s. In December 1860 he was chosen to represent Alabama on the so‑called Committee of Thirty‑Three, a special House committee formed in a last effort to avert secession. The committee endorsed the proposed Corwin Amendment to the United States Constitution, which would have barred Congress from ever abolishing slavery in the states.

With the outbreak of the American Civil War, Houston resigned his congressional seat and returned to his home in northern Alabama. Although two of his sons served in the Confederate Army, Houston himself took no active part in the Confederate government or military. By 1860 he had become a successful cotton planter and enslaver, holding 78 enslaved people on his property. During the war, in 1862, his estate was ransacked by Union forces under U.S. Army General Ivan Turchin, reflecting the harsh impact of the conflict on the Tennessee Valley. After the war, during early Reconstruction, Houston presented his credentials as a senator‑elect from Alabama, but the Republican majority in Congress refused to seat him, reflecting national tensions over the readmission of former Confederate states and their antebellum leaders. He attended President Andrew Johnson’s National Union Convention in Philadelphia in 1866, aligning himself with Johnson’s lenient Reconstruction policies and opposing the Radical Republicans. Houston sought a United States Senate seat again in 1867 but was defeated by former Governor John A. Winston, and, as during the Civil War, he played no direct governing role in Alabama’s formal Reconstruction governments.

Houston returned to statewide prominence in the mid‑1870s. In 1874 he ran for governor of Alabama as a Democrat and was elected with approximately 53 percent of the vote, defeating incumbent Republican Governor David P. Lewis. His victory marked the beginning of an unbroken line of Democratic governors in Alabama that continued until 1986 and formed part of the broader “Redemption” movement in the post‑Reconstruction South. Houston campaigned on a platform of “redeeming” the state from Republican rule, promising honesty and economy in government and denouncing what Democrats characterized as Republican fiscal mismanagement. At the same time, Democratic success in this period was accompanied by the intimidation and suppression of many Republican voters, particularly African Americans. As governor, Houston was identified with the Bourbon Democrat wing of his party, advocating conservatism, limited government, fiscal retrenchment, and white supremacy.

During his gubernatorial administration, Houston oversaw several significant policy initiatives and institutional changes. In 1875 the state legislature approved the creation of one of the nation’s first state public health boards, although the body received no appropriations until 1879. Confronted with a shrinking population and economic difficulties, he advocated immigration into Alabama to stimulate growth, but these efforts met with limited success. His administration expanded the state’s convict lease system, under which predominantly Black prisoners were leased to private contractors, a practice widely condemned by contemporaries and later historians. Houston also sought to reform Alabama’s educational system, but his plans were constrained by the heavy state debt incurred through railroad bond issues under previous administrations. To address this, he created a three‑person commission, chaired by himself and including Tristam B. Bethea of Mobile and Levi W. Lawler of Talladega, to investigate and settle the state’s bonded indebtedness. Because both Houston and Lawler had prior connections as railroad directors, the commission’s work drew criticism for potential conflicts of interest. The commission ultimately fixed the state’s “legitimate” debt at $12.5 million, a determination that most adversely affected the Republican‑aligned Alabama and Chattanooga Railroad bondholders. Houston also championed a constitutional convention to replace the Reconstruction‑era constitution of 1868. The resulting constitution of 1875, approved by the voters, declared that Alabama could never again secede from the United States, eliminated educational and property qualifications for voting or holding office, and abolished the office of lieutenant governor, while also constraining state spending and centralizing Democratic control.

Houston’s long personal life was closely intertwined with his public career. In May 1835 he married Mary I. Beatty, with whom he had eight children; four of these children died in childhood, reflecting the high mortality rates of the era. Mary Beatty Houston died before 1860. In 1861 he married Ellen Irvine, who bore him two additional children. His family connections, legal practice, and plantation interests anchored him in northern Alabama, particularly in Limestone County and the town of Athens, which became his principal residence in his later years.

After completing his second term as governor in 1878, Houston achieved his long‑sought goal of serving in the United States Senate. He was elected by the Alabama legislature as a Democrat to the Senate in 1878 and presented his credentials successfully, taking his seat during the post‑Reconstruction period. As a member of the Senate, George Smith Houston participated in the democratic process and represented the interests of his Alabama constituents during a time of political realignment in the South. His service in Congress—spanning his earlier House career and his final Senate term—occurred during a significant period in American history, from the antebellum era through secession, Civil War, and Reconstruction. Houston’s senatorial tenure was brief, however. He died in office at his home in Athens, Alabama, on December 31, 1879. He was buried in Athens City Cemetery and is listed among the members of the United States Congress who died in office in the nineteenth century.