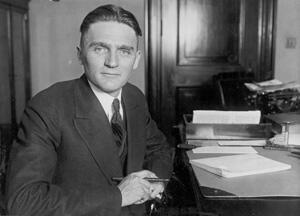

Senator Gerald Prentice Nye

Here you will find contact information for Senator Gerald Prentice Nye, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | Gerald Prentice Nye |

| Position | Senator |

| State | North Dakota |

| Party | Republican |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | December 7, 1925 |

| Term End | January 3, 1945 |

| Terms Served | 4 |

| Born | December 19, 1892 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | N000176 |

About Senator Gerald Prentice Nye

Gerald Prentice Nye (December 19, 1892 – July 17, 1971) was an American newspaper editor and politician who represented North Dakota in the United States Senate from 1925 to 1945. A member of the Republican Party, he served four terms in office and rose to national prominence in the 1930s as chair of the Special Committee on Investigation of the Munitions Industry, widely known as the Nye Committee, which examined the causes of United States involvement in World War I. Prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor, he became one of the most prominent opponents of American intervention in World War II and a leading figure in the isolationist movement.

Nye was born in Hortonville, Outagamie County, Wisconsin, the first of four children of Phoebe Ella (née Prentice) and Irwin Raymond Nye. His first name was pronounced with a hard “G.” Both of his grandfathers were Civil War veterans: Freeman James Nye served in the 43rd Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry Regiment, and George Washington Prentice served in the 3rd Wisconsin Volunteer Cavalry Regiment. When Nye was an infant, his parents moved to Wittenberg, Wisconsin, where his father became owner and editor of a small newspaper. Three younger siblings—Clair Irwin, Donald Oscar, and Marjorie Ella—were born there. His father was an ardent supporter of Progressive leader Robert M. La Follette, and Nye later recalled being taken as a boy to hear La Follette speak and to meet him afterward, an early political experience that foreshadowed Nye’s own service alongside Robert M. La Follette Jr. in the U.S. Senate. His uncle, Wallace G. Nye, served as mayor of Minneapolis, Minnesota, during Gerald’s teenage years. Nye’s mother, who suffered from tuberculosis and possibly asthma, made periodic trips to the South for her health but died on October 19, 1906, when he was thirteen. He was deeply affected by her death, though comforted by the presence of all four grandparents at her funeral. Nye graduated from Wittenberg High School in 1911 at age eighteen and then returned to Hortonville to live among his grandparents and pursue work in the newspaper trade.

From an early age, Nye and his brother Clair worked in their father’s newspaper office, where Gerald learned editing and reporting while Clair managed the presses. After finishing high school in 1911, Nye became editor of The Hortonville Review. By 1914 he had moved to Iowa as editor of the Creston Daily Plain Dealer. In May 1916 he purchased a weekly paper in Fryburg, North Dakota, The Fryburg Pioneer, and in 1919 he moved to Cooperstown, North Dakota, where he edited and published the Sentinel Courier. Through his editorials he emerged as a strong supporter of the agrarian reform movement, sharply criticizing both big government and big business and aligning himself with the interests of struggling farmers. On August 16, 1916, he married Anna Margaret Johnson in Iowa, where she lived with her maternal grandparents and had taken their name, Munch. The couple had three children—Marjorie (born 1917), Robert (born 1921), and James (born 1923)—who spent their early years in North Dakota and later grew up on Grosvenor Street in Washington, D.C., attending high school there. Each summer, Nye took his children to Yellowstone National Park, where his daughter Marjorie was a teenage friend of future President Gerald R. Ford.

Nye’s political career began in North Dakota, where his progressive views and advocacy for farmers led him to seek elective office. In 1924 he ran unsuccessfully, as a Democrat, for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. His opportunity for national office came the following year when U.S. Senator Edwin F. Ladd of North Dakota died on June 22, 1925. After consultations in the office of Governor Arthur G. Sorlie, Nye was selected to fill the vacancy. The appointment was controversial: conservative Republicans questioned whether the North Dakota legislature had authorized the governor to make such an appointment and worried that the progressive Nye would weaken their caucus. Although Nye and his young family moved to Washington in December 1925, the Senate delayed seating him until January 1926 while the dispute was resolved. His youth, lack of polish, and distinctive bowl haircut drew comment and ridicule in the capital, but he quickly established himself as an active, outspoken, and popular senator. North Dakota voters subsequently elected him to three full terms in 1926, 1932, and 1938 before he was defeated in 1944 by Democratic Governor John Moses.

During his two decades in the Senate, Nye served on the Foreign Relations Committee, the Appropriations Committee, the Defense Committee, and the Public Lands Committee. As chairman of the Committee on Public Lands and Surveys, he played a role in the later stages of the Teapot Dome investigations and in legislation leading to the formation of Grand Teton National Park. He was also instrumental in passing measures to protect public access to the nation’s seacoasts. Initially, Nye supported President Franklin D. Roosevelt and many aspects of the New Deal, particularly those that aligned with his long-standing advocacy of agricultural price supports and progressive economic reforms associated with Robert M. La Follette. Over time, however, his relationship with the Roosevelt administration deteriorated, and he emerged as a critic of certain New Deal policies and appointments; notably, he was one of only four senators to vote against the 1939 Supreme Court nomination of William O. Douglas.

Nye’s most famous work in Congress came as chair of the Special Committee on Investigation of the Munitions Industry, established in 1934. The committee investigated the influence of banking and armaments interests—whom Nye labeled “merchants of death”—on U.S. entry into World War I. Through widely publicized hearings, the committee examined wartime profits, the activities of the War Industries Board, and the relationships among arms manufacturers, financiers, and policymakers. Although the final report, supported by most committee members, concluded that the evidence did not substantiate the broad “merchants of death” conspiracy theory, Nye’s investigations did reveal extensive conflicts of interest and questionable practices in war contracting and procurement. The hearings intensified public skepticism about foreign entanglements and contributed to the growth of neutrality, non-interventionism, and disarmament sentiment in the 1930s. President Harry S. Truman later criticized the inquiry as “pure demagoguery in the guise of a Congressional Investigating Committee,” and Nye’s proposal to nationalize the arms industry failed. Nonetheless, the political uproar surrounding the committee helped generate support for a series of Neutrality Acts, passed between 1935 and 1937, which restricted private loans and arms sales to belligerent nations. These laws, later widely regarded as having unintentionally aided the rise of Nazi Germany, were largely repealed in 1941.

A leading isolationist, Nye became a central figure in the America First movement and helped establish the America First Committee to mobilize antiwar sentiment against U.S. involvement in World War II. He argued that American participation in what he called the “war for democracy” was being promoted by a nexus of arms manufacturers, international bankers, and sympathetic politicians. His isolationism and harsh rhetoric drew national attention and criticism, including satirical treatment in political cartoons by Dr. Seuss, who depicted him in caricatures attacking “defeatism” and riding a dying creature labeled “isolationism.” Nye’s views extended to the Spanish Civil War, where, despite his general opposition to foreign involvement, he supported the Republican faction and sought repeal of the embargo on arms sales to either side, contending that the embargo in practice favored the Nationalists. He publicly criticized individuals such as Marcelino Garcia Rubiera and Manuel Diaz Riestra for illegally shipping supplies to the Nationalists. Even as tensions with Germany escalated, Nye sometimes discounted reports of German aggression; after the German submarine U-69 sank the SS Robin Moor in May 1941, he stated that he would be “very much surprised if a German submarine had done it because it would be to their disadvantage” to torpedo the ship.

Nye’s isolationism was frequently intertwined with controversial and often antisemitic rhetoric. Like many conservative isolationists of the era, he subscribed to conspiracy theories about Jewish influence in finance and the motion picture industry. In 1941, during Senate subcommittee hearings on alleged “war-mongering” in Hollywood films, he charged that those responsible for such motion pictures were “born abroad” and accused the film industry—particularly Warner Brothers—of attempting to “drug the reason of the American people” and “rouse war fever.” The Jewish Telegraphic Agency reported in September 1941 that Nye had made “anti-Jewish insinuations” and “anti-Jewish accusations,” and the New York Post accused him of delivering a “crudely anti-Semitic radio broadcast.” He was criticized by Jewish employees of the New York Daily News and by former Republican presidential nominee Wendell Willkie, who condemned Nye and fellow isolationist Senator Burton Wheeler for their attacks on Jews in the American film industry. Nye claimed to have “Jewish friends,” and the State Historical Society of North Dakota later credited him with helping Herman Stern, a German Jewish immigrant businessman in North Dakota, and Stern’s wife Adeline bring more than 140 Jewish refugees to the United States in the 1930s and 1940s. Nonetheless, his public statements included warnings that Americans seeking a scapegoat for war might direct their “wrath” toward “foreign-born Jews,” and he asserted that the American movie industry was run by “foreign-born Jews,” ignoring the decisive role of non-Jewish American banks and financial institutions such as Chase National Bank, Atlas Corporation, and the Rockefellers in financing Hollywood.

On December 7, 1941, the day of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Nye was in Pittsburgh to address an America First meeting. A reporter from the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette informed him of the attack before his speech, but Nye, skeptical of the initial report, did not relay the news to the audience. During his remarks, the reporter passed him a note stating that Japan had declared war; Nye read it but continued speaking, announcing the attack only at the end of his hour-long address and describing it as “the worst news that I have encountered in the last 20 years.” Despite his long-standing opposition to intervention, he joined the rest of the Senate the following day in voting unanimously to declare war on Japan. His isolationist reputation persisted, however, and in April 1943 a confidential report on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee prepared by Isaiah Berlin for the British Foreign Office described him as a “notorious fire-eating Anglophobe Isolationist,” noted that much popular anti-British feeling in the United States stemmed from publicity surrounding his munitions investigation, and alleged that he had “Fascist connexions” and worked closely with like-minded senators inside and outside the chamber. In the 1944 election, amid changing public attitudes during wartime, Nye lost his bid for a fifth term to Governor John Moses.

After leaving the Senate in January 1945, Nye chose to remain in the Washington, D.C., area. He and his second wife had earlier purchased three acres of pasture land in Chevy Chase, Maryland, part of a farm on a hill above Rock Creek Park, where they raised their younger children. In March 1940 he had divorced his first wife, Anna, and on December 14, 1940, he married A. Marguerite Johnson, an Iowa schoolteacher who had also used the surname Johnson; they had three children, all born in Washington, D.C.: Gerald Jr. (born 1943), Richard (born 1944), and Marguerite (born 1950). Nye entered private business as organizer and president of Records Engineering, Inc., a Washington firm that, in the pre-computer era, specialized in creating, organizing, and managing records for industrial and government clients. In 1960 he returned to federal service when he was appointed to the Federal Housing Administration as assistant to the commissioner with responsibility for housing for the elderly. Three years later, in 1963, he joined the professional staff of the U.S. Senate Special Committee on Aging, continuing his involvement in public policy related to older Americans. In 1966 colleagues and former associates honored him with a retirement celebration at the U.S. Capitol, hosted by Senate Minority Leader Everett Dirksen and attended by Senators Robert F. Kennedy and Edward M. Kennedy. Dirksen presented Nye with a typewriter and desk lamp, urging him to begin work on his memoirs. In subsequent years, Nye served as a consultant to churches and private organizations seeking federal funds to construct retirement housing. A Freemason, he was also an active member of Grace Lutheran Church in Washington, D.C.

Nye’s later years were marked by serious health problems related in part to a lifetime of heavy smoking. He developed arterial disease so advanced that the arteries in his legs were surgically replaced with plastic vessels, then a state-of-the-art procedure. Near the end of his life he suffered a blood clot that traveled to his lung. While he was still weak and recovering from that episode, a physician mistakenly prescribed a drug containing penicillin, despite Nye’s known allergy to it. He died as a result of that error on July 17, 1971, at the age of seventy-eight.