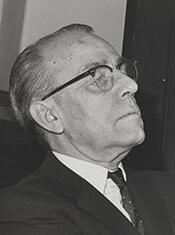

Representative H. R. Gross

Here you will find contact information for Representative H. R. Gross, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | H. R. Gross |

| Position | Representative |

| State | Iowa |

| District | 3 |

| Party | Republican |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | January 3, 1949 |

| Term End | January 3, 1975 |

| Terms Served | 13 |

| Born | June 30, 1899 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | G000495 |

About Representative H. R. Gross

Harold Royce Gross (June 30, 1899 – September 22, 1987) was a Republican United States Representative from Iowa’s 3rd congressional district who served thirteen consecutive terms in the U.S. House of Representatives from January 3, 1949, to January 3, 1975. Over more than a quarter-century in Congress, he became nationally known for his relentless opposition to what he regarded as wasteful federal spending, a role that prompted Time magazine to label him “the useful pest.” A member of the Republican Party, he participated actively in the legislative process during a significant period in American history, representing the interests of his Iowa constituents while cultivating a reputation as one of the chamber’s most vigilant fiscal watchdogs.

Gross was born on his parents’ 240-acre farm near Arispe, in Union County, Iowa. He attended rural schools and later high school in Creston, Iowa. In 1916, after completing his sophomore year of high school, he concealed his youth in order to enlist in military service. He first served with the First Iowa Field Artillery in the Pancho Villa Expedition on the Mexican border. During World War I he served in France with the United States Army from 1917 to 1919. After his discharge, he briefly attended Iowa State College (now Iowa State University) in an electrical engineering program before transferring to the University of Missouri School of Journalism in Columbia, reflecting an early and decisive turn toward a career in reporting and public affairs.

Beginning in 1921, Gross worked as a newspaper reporter and editor for various newspapers, a career that lasted until 1935. Among his positions, he edited the Iowa Union Farmer, the publication of the Iowa Farmers’ Union, from 1929 to 1935, and he wrote and spoke on behalf of the Farmers’ Holiday Association, a farm protest movement of the early 1930s. While covering the Iowa statehouse as a reporter, he met Hazel E. Webster, who was then serving as secretary to the Iowa Attorney General. They married in 1929 and later had two sons, Phillip and Alan. In 1935, Gross moved into radio journalism, becoming a news commentator for WHO (AM) in Des Moines, Iowa, where one of his fellow on-air broadcasters was a young Ronald Reagan. His growing prominence as a radio commentator helped establish the plain-spoken, populist style that would later characterize his political career.

Gross first sought major public office in 1940, when he challenged Iowa’s sitting Republican governor, George A. Wilson, in the Republican primary. Running what newspapers called a “sight-unseen” campaign, he confined his efforts to radio addresses, declined all invitations for personal appearances, and made no platform speeches. Despite this unconventional approach, he lost the primary by only 15,781 votes out of more than 330,000 cast, the closest primary race in Iowa in nearly thirteen years. His campaign was hampered by a statement he had made seven years earlier, while associated with the Farmers’ Holiday Association, that appeared to approve of an episode of mob violence against a judge to stop a foreclosure. After his defeat, Gross left Iowa for a time, joining a radio station in Ohio and later moving to Indiana. Following World War II, he returned to Iowa and resumed his broadcasting career as a radio newscaster at KXEL in Waterloo, further solidifying his public profile in the state.

In 1948, Gross entered congressional politics by challenging incumbent Republican Representative John W. Gwynne for the nomination in Iowa’s 3rd congressional district. Running without the support of the party organization, he wrested the Republican nomination away from Gwynne in the primary. In the general election, held in a year when Democratic President Harry S. Truman unexpectedly carried Iowa and Democrat Guy Gillette defeated Republican George A. Wilson for the U.S. Senate, Gross nonetheless won his first of many landslide victories. He took office on January 3, 1949, and would be re-elected twelve times, serving continuously until January 3, 1975. In his narrowest race, he was the only Republican member of Iowa’s U.S. House delegation to survive the Democratic landslide of 1964. Over the course of his thirteen terms, he contributed consistently to the legislative process and became one of the House’s most recognizable voices on matters of federal expenditure.

During his congressional service, Gross earned what his successor, future Senator Charles Grassley, called “a legendary reputation as watchdog of the Treasury.” He rarely missed a roll call vote and often remained in the House chamber between votes, listening closely to debate and scrutinizing the details of pending bills, especially appropriations and other spending measures. He denounced, among other things, the Marshall Plan, the funeral arrangements for President John F. Kennedy (including the appropriation for fuel for the eternal flame at Arlington), the size of the White House security detail, the Peace Corps, the U.S. space program, and a wide range of foreign aid programs. His independence from party leadership was widely noted; then–House Minority Leader Gerald Ford remarked that “there are three parties in the House: Democrats, Republicans, and H. R. Gross.” Defying pressure from the Eisenhower administration to support a foreign-aid economic-development measure, Gross quipped, “I took my last marching orders in 1916–19,” a reference to his World War I service.

Gross’s voting record reflected a combination of staunch fiscal conservatism and selective support for social and regulatory measures. He opposed many large federal spending initiatives and famously refused to participate in taxpayer-funded congressional “junkets,” or overseas fact-finding trips. When he retired, his colleagues in the House contributed to send him and his wife Hazel, who had managed his congressional office without pay, on a round-the-world trip; accepting the gift, he remarked, “Wherever we go, I am sure I’ll see you all on your taxpayers’ junkets!” He took an early stand in the 1960s against the practice of retired military personnel drawing both a military pension and a federal salary, and he opposed restoring former President Dwight D. Eisenhower to his five-star generalship unless Congress stipulated that Eisenhower would receive only his presidential pension and not a general’s salary as well. Gross later said that he had only one regret about his congressional career: voting “present” rather than “nay” on the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution in 1964, explaining that the Vietnam War ultimately cost too much in lives and treasure. Libertarian theorist Murray Rothbard praised Gross in the Libertarian Forum, asserting that he had the best voting record in Congress from a libertarian standpoint and hailing him as “the Grand Old Man of the Old Right.”

On civil rights and domestic policy, Gross’s record was complex. He voted in favor of the Civil Rights Acts of 1960 and 1968 and supported the 24th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which abolished the poll tax in federal elections. He voted against the Civil Rights Acts of 1957 and 1964 and opposed the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Despite his reputation as a fiscal hawk, he supported amendments to strengthen Social Security, backed the Celler–Kefauver Act targeting anti-competitive business practices, and voted for measures such as public housing legislation, the Railroad Retirement Act, the Equal Rights Amendment of 1971, and the Oil Pollution Act of 1973. He was also one of the few members to oppose the Uniform Monday Holiday Act of 1968, arguing that shifting most federal holidays to Mondays would deprive retail workers of their holidays because stores would remain open.

Gross’s personal lifestyle mirrored his public advocacy of frugality and restraint. He lived modestly in the Washington area, rarely attending the parties or social functions that were common in congressional life, and was remembered as something of an outsider who preferred to spend evenings in his townhouse watching professional wrestling on television. In 1966, at the height of the Vietnam War, he protested an extravagant White House ball that continued until 3 a.m. while American soldiers were dying overseas by reciting Alfred Noyes’s poem “The Victory Ball” on the House floor; the poem condemns the hedonism of a British Armistice ball and includes the line “under the dancing feet are the graves.” Even those whose programs he frequently criticized could speak warmly of him; longtime House Armed Services Committee Chairman Carl Vinson, whose defense spending bills often drew Gross’s fire, remarked that “there is really no good debate unless the gentleman from Iowa is in it.” In recognition of his distinctive presence, House leaders made a special exception to the usual practice of numbering bills consecutively: each session, the number H.R. 144—one gross, in arithmetic terms—was reserved for one of his bills, making its designation a numerical play on his name.

After choosing not to run for re-election in 1974, Gross retired from Congress at the end of his thirteenth term in January 1975. He and Hazel continued to reside in Arlington, Virginia, where they had long made their home during his years in office. Harold Royce Gross died on September 22, 1987, at a Veterans Administration hospital in Washington, D.C., due to complications from Alzheimer’s disease. He was buried with military honors in Arlington National Cemetery, a final resting place that reflected both his World War I service and his long tenure in the House of Representatives.