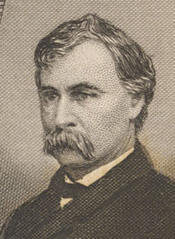

Representative Henry Winter Davis

Here you will find contact information for Representative Henry Winter Davis, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | Henry Winter Davis |

| Position | Representative |

| State | Maryland |

| District | 3 |

| Party | Unconditional Unionist |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | December 3, 1855 |

| Term End | March 3, 1865 |

| Terms Served | 4 |

| Born | August 16, 1817 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | D000104 |

About Representative Henry Winter Davis

Henry Winter Davis (August 16, 1817 – December 30, 1865) was a United States Representative from Maryland’s 4th and 3rd congressional districts, serving in the House of Representatives from 1855 to 1865. Over the course of four terms in Congress, he became one of the most prominent Radical Republicans during the Civil War era and a leading figure among Maryland’s Unconditional Unionists. He was widely regarded as a driving force behind the abolition of slavery in Maryland in 1864, and it was largely because of his efforts that Maryland did not secede from the Union. An influential legislator and orator, he was the author and primary House sponsor of the Wade–Davis Bill of 1864, a Reconstruction measure that President Abraham Lincoln ultimately refused to sign.

Davis was born on August 16, 1817, and by inheritance was himself a slaveholder, yet from an early period he became imbued with strong anti-slavery views. Details of his formal education are less prominent in the historical record than his intellectual and professional pursuits, but he emerged as a well-educated lawyer and writer, active in public debate well before his election to Congress. His early life in a slaveholding society, combined with his growing opposition to the institution of slavery, shaped the distinctive blend of Unionism and radical reform that would later define his political career.

Davis began his political life as a member of the Whig Party, aligning himself with its nationalist economic outlook and opposition to Democratic administrations. After the disintegration of the Whig Party in the early 1850s, he joined the Know Nothing–influenced American Party, reflecting the turbulent realignment of national politics in the decade before the Civil War. Elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1855, he served as a member of the American Party from 1855 to 1861, representing Maryland in the 34th, 35th, and 36th Congresses. During this period he became known for his sharp rhetoric and nativist views, particularly his hostility toward Irish Catholic immigration. In 1856, speaking on the floor of Congress after the election of Democrat James Buchanan, he charged that “foreign allies” and “vast multitudes of foreign-born citizens” ignorant of American interests had decided the result, and he condemned what he saw as the intrusion of religious influence into politics.

Davis’s independence from Maryland’s more conservative political establishment became evident during the contest over the speakership at the opening of the 36th Congress in 1859. He voted with the Republicans in that protracted struggle, a step that provoked a vote of censure from the Maryland legislature, which went so far as to call upon him to resign his seat. In the 1860 presidential election, he was not yet prepared to join the Republican Party and declined consideration for the Republican nomination for Vice President of the United States. Instead, he supported the Constitutional Union ticket of John Bell and Edward Everett, which sought to avert sectional conflict by emphasizing loyalty to the Union and the Constitution. Defeated for reelection to Congress in 1860, Davis spent the critical winter of 1860–1861, between the secession of several Southern states and the firing on Fort Sumter, engaged in various compromise efforts aimed at preserving the Union.

After Abraham Lincoln’s election and the outbreak of the Civil War, Davis decisively aligned himself with the Union cause and emerged as the leader of Maryland’s Unconditional Unionists. He returned to Congress after winning election in 1862, this time as an Unconditional Unionist, and quickly associated himself with the Radical Republicans, who favored a hard war against the Confederacy and a sweeping transformation of Southern society. His service in Congress from 1855 to 1865 thus spanned the collapse of the old party system, the secession crisis, and the Civil War itself, during which he consistently participated in the legislative process and represented the interests of his Maryland constituents in a period of extraordinary national upheaval.

From December 1863 to March 1865, Davis served as chairman of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs. In that capacity he took a strong interest in the international dimensions of the Civil War, particularly the French intervention in Mexico under Emperor Napoleon III. Unwilling to leave such delicate questions entirely in the hands of President Lincoln and Secretary of State William H. Seward, he brought in a report in 1864 that was sharply hostile to France’s actions in Mexico. The House of Representatives adopted his report, though the Senate did not, illustrating both his influence and the limits of congressional assertiveness in foreign policy during wartime.

Davis is best remembered for his role in shaping congressional Reconstruction policy. With other Radical Republicans, he was a bitter opponent of Lincoln’s comparatively lenient plan for restoring the seceded states to the Union. On February 15, 1864, as a leading member of the House, he reported from committee a measure that became known as the Wade–Davis Bill, co-sponsored with Senator Benjamin Wade of Ohio. The bill placed Reconstruction under congressional control and required that, as a condition of readmission, former Confederate states disfranchise important civil and military officers of the Confederacy, abolish slavery, and repudiate all debts incurred by or with the sanction of the Confederate government. In a major speech supporting the measure, Davis argued that until Congress recognized a government established under its auspices, “there was no government in the rebel states save the authority of Congress.” The bill, the first formal expression by Congress on Reconstruction, passed both houses only in the closing hours of the session on July 2, 1864.

President Lincoln declined to sign the Wade–Davis Bill, allowing it to fail by pocket veto, and on July 8, 1864, he issued a proclamation explaining his position and defending his own Reconstruction policy. In response, on August 4, 1864, Davis joined Senator Wade in issuing a public manifesto “To the Supporters of the Government,” which vehemently denounced Lincoln for encroaching on the constitutional prerogatives of Congress and insinuated that the president’s policy would leave slavery effectively unimpaired in the reconstructed states. Davis continued to criticize what he saw as the rise of executive will over the rule of law, later declaring in debate that when he had entered Congress ten years earlier, the United States had been “a government of law,” but that he had lived to see it become “a government of personal will.” Although he was one of the radical leaders who initially preferred John C. Frémont to Lincoln in the 1864 presidential election, he eventually withdrew his opposition and supported Lincoln’s reelection. Lincoln, for his part, remarked on Election Night 1864 that Davis had been “very malicious” against him and had only injured himself by it, noting that he had originally come to Washington as Davis’s friend, partly because Davis was a cousin of Lincoln’s intimate friend, Judge David Davis.

In addition to his work on Reconstruction and foreign affairs, Davis was an early and consistent advocate of using African American manpower in the Union war effort, favoring the enlistment of Black soldiers before this became broadly accepted policy. In July 1865, after the war’s end, he publicly supported extending the right to vote to African Americans, placing himself among the more advanced voices on Black suffrage at that time. He was also a man of letters; among his writings was “The War of Ormuzd and Ahriman in the Nineteenth Century,” published in 1853, which reflected his wide-ranging intellectual interests and rhetorical skill.

Davis did not stand for reelection to Congress in 1864, and his formal congressional service concluded in March 1865. His later months were marked by continued engagement in public debate over Reconstruction and civil rights, but his career was cut short by his death in Baltimore, Maryland, on December 30, 1865. He was interred in Greenmount Cemetery in Baltimore. Henry Winter Davis was closely connected to other notable public figures: he was a cousin of David Davis, who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States and later as a U.S. Senator from Illinois, and he was also a first cousin of Brevet Brigadier General Moses B. Walker, who served as an associate justice of the Texas Supreme Court.