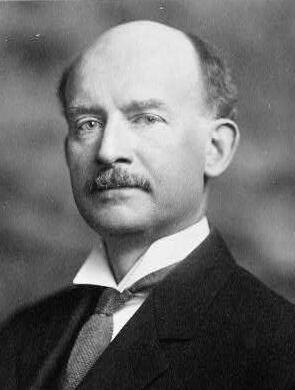

Representative Henry George

Here you will find contact information for Representative Henry George, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | Henry George |

| Position | Representative |

| State | New York |

| District | 21 |

| Party | Democratic |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | April 4, 1911 |

| Term End | March 3, 1915 |

| Terms Served | 2 |

| Born | November 3, 1862 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | G000126 |

About Representative Henry George

Henry George Jr. (November 3, 1862 – November 14, 1916) was an American journalist, author, and Democratic politician who served as a Representative from New York in the United States Congress from 1911 to 1915. He was born in San Francisco, California, the eldest child of the political economist and social philosopher Henry George (September 2, 1839 – October 29, 1897) and Annie Corsina Fox George, an Irish Catholic from Sydney, Australia. His father, a former foremast boy and typesetter who had risen to prominence as a journalist and reformer, and his mother, who had eloped with Henry George Sr. in San Francisco on December 3, 1861, raised their family in conditions that ranged from near-starvation poverty to modest security as the elder George’s reputation grew. The younger Henry George thus came of age in a household deeply marked by economic hardship, intellectual ferment, and intense political debate.

Henry George Jr.’s early education was informal and heavily influenced by his father’s deistic humanitarianism and reformist outlook. While his grandfather, Richard S. H. George, had been a devout Episcopalian publisher of religious texts in Philadelphia and had sent Henry George Sr. to the Episcopal Academy there, the elder George had broken with strict religious orthodoxy and embraced a broad, humanistic deism. In New York and California, the younger George grew up amid his father’s circle of journalists, labor leaders, and reformers, absorbing at close range the arguments that would shape the economic philosophy known as Georgism—the belief that individuals should own the full value of what they themselves produce, while the economic value of land and natural resources should belong equally to all. Though Annie George remained Catholic, Henry George Jr. later wrote that he and his siblings were influenced more by their father’s deism and humanism than by formal church doctrine, and his intellectual formation reflected the same combination of wide reading, public lectures, and practical political experience that had characterized his father’s self-education.

Before entering national politics, Henry George Jr. followed his father into journalism and public affairs. He witnessed the elder George’s rise from San Francisco printer and editor—who had worked for the San Francisco Times, founded the San Francisco Daily Evening Post, and edited the Democratic anti-monopoly paper the Reporter—to international prominence as the author of Progress and Poverty (1879), a treatise that sold millions of copies worldwide and examined the paradox of growing poverty amid technological and economic progress. The younger George saw at first hand how his father’s criticism of railroad and mining interests, land speculation, and monopoly power, and his advocacy of a single tax on land values, free trade, the secret ballot, Pigouvian taxation, and public ownership of natural monopolies, could mobilize mass movements. He also observed the political costs of such positions: the elder George’s failed bid for the California State Assembly in 1871, his struggles to keep his newspaper afloat, and his eventual appointment as State Inspector of Gas Meters in Sacramento from 1876 to 1880, during which he completed Progress and Poverty with the help of advisers such as John Swett, Andrew Smith Hallidie, James McClatchy, James G. Maguire, and Edward Robeson Taylor.

The political environment in which Henry George Jr. matured was further shaped by his father’s campaigns and controversies in the 1870s and 1880s. Henry George Sr. had first articulated his land and monopoly critique in the 1868 article “What the Railroad Will Bring Us,” and he later gained national attention with writings such as the 1869 essay “The Chinese in California” and his involvement with the anti-Chinese Workingmen’s Party, even as he quarreled with its leader Denis Kearney. He was nominated, but not elected, as a delegate to California’s Second Constitutional Convention in 1878 and received only two votes in the California State Senate’s 1881 balloting for United States Senator, despite being praised by State Senator Warren Chase as the peer of John Stuart Mill, David Ricardo, and Adam Smith. In 1880 the elder George moved the family to New York City, where he allied himself with Irish nationalists and twice ran for mayor—first in 1886 as the United Labor Party nominee, finishing with 31 percent of the vote and ahead of Theodore Roosevelt, and again in 1897 as the Jefferson Democracy nominee, when he died in New York City on October 29, 1897, during the campaign. These experiences provided Henry George Jr. with a living tutorial in urban politics, labor issues, and electoral strategy in New York.

Against this backdrop, Henry George Jr. developed his own career as a writer and public figure in New York, carrying forward many of his father’s themes while adapting them to the political and economic conditions of the early twentieth century. A committed Democrat, he engaged with questions of land policy, taxation, monopoly, and labor rights that had animated Georgist reformers since the late nineteenth century. His work as a journalist and lecturer helped sustain and popularize Georgist ideas in the United States and other Anglophone countries after his father’s death, at a time when Progressive Era reform movements were grappling with industrial concentration, urban poverty, and political corruption. The younger George’s proximity to these debates, and to the organizations and political leaders who championed Georgism, positioned him as both an heir to and an interpreter of his father’s economic philosophy.

Henry George Jr. entered national office when he was elected as a Democrat to the United States House of Representatives from New York, serving two consecutive terms from March 4, 1911, to March 3, 1915. As a member of the House of Representatives during a significant period in American history marked by Progressive Era reforms and the presidency of Woodrow Wilson, he participated in the legislative process and represented the interests of his New York constituents. In Congress he contributed to debates over economic and social policy that echoed many of the concerns first articulated by his father, including the relationship between wealth and poverty, the regulation of monopoly power, and the proper basis of taxation in an industrial democracy. His service in Congress thus linked the late nineteenth-century Georgist critique of land and monopoly with the broader reform currents of the early twentieth century, and ensured that the Georgist perspective had a voice in federal deliberations.

After leaving Congress in 1915, Henry George Jr. remained associated with the causes and ideas that had defined his public life and family legacy. He continued to be identified with Georgist reformers who, in the decades after Henry George Sr.’s death, worked to advance land value taxation and related policies as remedies for inequality and economic instability. By the time of his own death on November 14, 1916, he had helped to carry the Georgist tradition from its origins in the California and New York politics of the 1870s and 1880s into the institutional framework of the United States Congress. In doing so, he bridged the worlds of journalism, social philosophy, and electoral politics, and ensured that the ideas first set out in Progress and Poverty and other writings remained part of the American political conversation well into the twentieth century.