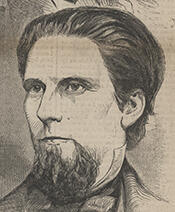

Representative Jabez Lamar Monroe Curry

Here you will find contact information for Representative Jabez Lamar Monroe Curry, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | Jabez Lamar Monroe Curry |

| Position | Representative |

| State | Alabama |

| District | 7 |

| Party | Democratic |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | December 7, 1857 |

| Term End | March 3, 1861 |

| Terms Served | 2 |

| Born | June 5, 1825 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | C001003 |

About Representative Jabez Lamar Monroe Curry

Jabez Lamar Monroe Curry (June 5, 1825 – February 12, 1903) was an American Democratic politician, educator, and diplomat from Alabama who served in the state legislature and the United States Congress, and later as a leading advocate of public education in the post–Civil War South. A member of the Democratic Party, he represented Alabama in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1857 to 1861, during a critical period in the nation’s history preceding the Civil War. He also served as an officer of the Confederate States Army and as a member of the Provisional Congress of the Confederate States. Curry was a slave owner and an outspoken defender of slavery before and during the Civil War, and he later became a prominent, if complex, figure in Southern educational reform.

Curry was born in Lincoln County, Georgia, the son of planter William Curry and Susan Winn Curry. His family moved to Alabama during his youth, and he grew up in a slaveholding household that was part of the plantation society of the antebellum South. Through his father, he was related to Mirabeau Buonaparte Lamar, the second president of the Republic of Texas; Lamar had married Tabitha Burwell Jordan, Curry’s aunt. Curry attended the University of Georgia, where he joined the Phi Kappa Literary Society and graduated in 1843. He subsequently studied law at Harvard Law School. While at Harvard, he was influenced by the educational ideas of reformer Horace Mann, whose lectures helped shape Curry’s early commitment to the principle of free, universal education, even as Curry remained deeply embedded in the slaveholding culture of the South.

After completing his legal studies, Curry became an attorney in Alabama and entered public life. He served in the Mexican–American War in 1848, reflecting the pattern of many young Southern politicians whose early careers combined military and legal experience. He was elected to the Alabama State Legislature, serving terms in 1847, 1853, and 1855. As a legislator, he aligned with the Democratic Party and the pro-slavery, states’ rights positions that dominated Alabama politics in the 1850s. His growing prominence in state affairs led to his election to the United States House of Representatives, where he served two terms from March 4, 1857, to January 21, 1861. In Congress, Curry participated in the legislative debates of the late antebellum era and represented the interests of his Alabama constituents as sectional tensions over slavery and secession intensified.

Curry’s service in Congress coincided with the final years of the Union before the outbreak of the Civil War. A committed Southern Democrat, he supported the secessionist cause. After Alabama seceded from the Union in early 1861, he resigned his seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. He then served in the Provisional Congress of the Confederate States, helping to establish the legislative framework of the new Confederate government. During the Civil War, he was commissioned as a lieutenant colonel in the Confederate Army and served as a staff aide to General Joseph E. Johnston and later to General Joseph Wheeler. His wartime record combined legislative and military service on behalf of the Confederacy, and he remained an advocate of slavery and white supremacy during this period.

Following the Confederacy’s defeat, Curry studied for the ministry and became a preacher, but his most enduring postwar work lay in the field of education. He emerged as a leading Southern advocate of public schooling, traveling widely to promote free education for both whites and Blacks in the South, though within a segregated and racially hierarchical framework. He supported the establishment of state normal schools for teacher training, the development of graded public schools, and the improvement of rural education. From 1865 to 1868 he served as president of Howard College in Alabama, an institution now known as Samford University. He later joined the faculty of Richmond College in Virginia (now the University of Richmond), where he was a professor of history and literature. Despite his advocacy of schooling for African Americans, Curry’s views on race remained deeply paternalistic; he favored a more vocational style of education for Black students than for whites, a position that paralleled the approach of Booker T. Washington at Tuskegee Institute.

Curry became one of the most influential Southern intermediaries between philanthropic education funds and local school systems. From 1881 until his death in 1903, he served as the agent for both the Peabody Education Fund and the John F. Slater Fund, organizations dedicated to aiding schools in the South, particularly in the aftermath of Reconstruction. In this role he was instrumental in the founding of the Southern Education Board and in the establishment of the first state normal school in Virginia, an institution that later became Longwood University. He lectured extensively on the need for improved public education and worked to persuade Southern leaders to invest in school systems. At the same time, his public statements revealed the racial and political limits of his reformism. In 1889, he characterized Reconstruction as an effort to degrade the white man and give supremacy to the “negro,” reflecting his opposition to Black political equality even as he supported expanding educational access.

Curry also played a visible role in the rhetoric of sectional reconciliation between North and South in the late nineteenth century. Historian Paul H. Buck later credited him with a major part in promoting reunification. Addressing the 1896 national convention of the United Confederate Veterans, Curry argued that the organization was not formed “in malice or in mischief, in disaffection, or in rebellion, nor to keep alive sectional hates, nor to awaken revenge for defeat, nor to kindle disloyalty to the Union.” He maintained that honoring Confederate soldiers could be “perfectly consistent with loyalty to the flag and devotion to the Constitution and the resulting Union.” The convention adopted a resolution echoing his view, declaring that the former Confederate had “returned to the Union as an equal, and he remains in the Union as a friend,” a “cheerful, frank citizen of the United States, accepting the present, trusting the future, and proud of the past.”

In addition to his educational work, Curry held important diplomatic posts. President Grover Cleveland appointed him envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary to Spain, a position he held from 1885 to 1888. In that role he represented U.S. interests in Madrid during a period of evolving American engagement with Spain and its remaining colonial possessions. In 1902, President Theodore Roosevelt again called on Curry’s services, appointing him ambassador extraordinary to Spain on the occasion of the coming of age of King Alfonso XIII. His diplomatic service was recognized by foreign and domestic honors, including the Royal Order of Charles III from Spain and several honorary degrees from American institutions.

Curry was a prolific writer on education, government, and history. His works included “Constitutional Government in Spain” (1889), “William Ewart Gladstone” (1891), and “The Southern States of the American Union” (1894), as well as “Difficulties, Complications, and Limitations Connected with the Education of the Negro” (1895), which reflected both his advocacy of schooling for African Americans and his belief in racially differentiated educational aims. He also authored “Civil History of the Government of the Confederate States, with Some Personal Reminiscences” (1901) and “The South in the Olden Time” (1901), contributing to the postwar literature that interpreted the Confederate experience and the antebellum South for later generations.

Jabez Lamar Monroe Curry died on February 12, 1903, and was buried in Richmond, Virginia. His wife was buried in Talladega, Alabama, where the couple had earlier lived. Their residence there, known as the J.L.M. Curry House or Curry-Burt-Smelley House, was later designated a National Historic Landmark and preserved as a site of historical interest. Curry’s memory was honored in multiple ways in the early twentieth century. One of Alabama’s two statues in the National Statuary Hall Collection at the United States Capitol was dedicated to him in 1908; sculpted by Dante Sodini, it remained there until 2009, when Alabama replaced it with a statue of Helen Keller. Curry’s statue was then transferred to Samford University, where it was displayed in the university center until that building closed for renovation in 2018, after which the statue was returned to the Alabama Department of Archives and History.

Educational institutions also bore his name. In 1905, the University of Virginia named its school of education the Curry School of Education, in accordance with a stipulation attached to a donation by John D. Rockefeller Sr. that year. Over time, however, Curry’s legacy came under renewed scrutiny because of his pro-slavery speeches, his service in the Confederate House of Representatives, and his continued defense of white supremacy during and after Reconstruction. In 2020, the University of Virginia’s president endorsed a recommendation to remove Curry’s name from the school as part of a broader institutional effort to confront the history of racism and slavery, and in September of that year the university’s board of visitors voted to do so. Other buildings named for him include Curry Hall dormitory at Longwood University and the Curry Building at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. His life and career, encompassing pro-slavery advocacy, Confederate service, and later leadership in Southern educational reform, have remained subjects of ongoing historical evaluation and debate.