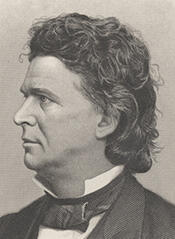

Representative James Mitchell Ashley

Here you will find contact information for Representative James Mitchell Ashley, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | James Mitchell Ashley |

| Position | Representative |

| State | Ohio |

| District | 10 |

| Party | Republican |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | December 5, 1859 |

| Term End | March 3, 1869 |

| Terms Served | 5 |

| Born | November 14, 1824 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | A000314 |

About Representative James Mitchell Ashley

James Mitchell Ashley (November 14, 1824 – September 16, 1896) was an American politician, abolitionist, and railroad executive who served as a Representative from Ohio in the United States Congress from 1859 to 1869. A member of the Republican Party, he represented Ohio’s 5th congressional district for two terms (1859–1863) and the 10th congressional district for three terms (1863–1869), contributing to the legislative process during five terms in office. His service in Congress occurred during a significant period in American history, encompassing the Civil War and the early years of Reconstruction, and he became a prominent leader of the Radical Republicans, noted especially for his role in the abolition of slavery and the impeachment proceedings against President Andrew Johnson.

Ashley was born in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, on November 14, 1824, to John Ashley, a bookbinder and Campbellite preacher who evangelized in Kentucky and what is now West Virginia, and Mary A. (Kilpatrick) Ashley of Kentucky. Raised in the Ohio River valley, he witnessed coffles of chained enslaved people being marched to the Deep South, boys his own age being sold, and white men refusing to let their cattle drink from streams where his father had baptized enslaved persons. These experiences shaped his moral and political outlook, leading him to detest slavery—“the peculiar institution”—which he regarded as a violation of Christian principles and the work of an entrenched oligarchy. Although his father hoped he would follow family tradition and become a Baptist minister, Ashley resisted that path, setting the stage for a life of political and social dissent.

Largely self-taught in elementary subjects, Ashley rejected formal theological education. At about age 14 he ran away from home to work as a cabin boy on boats on the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, later becoming a clerk on those vessels. By 1839, while still a teenager, he had begun assisting enslaved people to escape, and he later recalled with pride the families he helped as a 17‑year‑old. He recounted that when he left home his father’s parting words were, “You’re on the straight road to Hell, boy!” Two decades later, upon taking his seat in the U.S. House of Representatives, Ashley’s first act in his Washington, D.C., office was to write his father on official congressional stationery: “Dear Father, I have just arrived!” In 1848 he settled in Portsmouth, Ohio, where he entered journalism, working first for the Portsmouth Dispatch and then as editor of the Portsmouth Democrat. Admitted to the Ohio bar in 1849, he chose not to practice law. Instead, his growing abolitionist activity led him and his wife to flee prosecution under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, and by 1851 they had moved to Toledo, Ohio, where he opened a drug store that was soon burned down, likely in reaction to his antislavery stance.

In Toledo, Ashley became deeply involved in the emerging Republican Party, campaigning for presidential candidate John C. Frémont and Congressman Richard Mott. He married Emma Jane Smith in 1851, and the couple had four children; among their descendants is his great‑grandson, U.S. Representative Thomas W. L. Ashley, and a later namesake, James Ashley IV, a portraitist in Chicago. By 1858 Ashley had risen to lead the Ohio Republican Party. A committed abolitionist, he traveled with Mary Brown, the wife of John Brown, to Brown’s execution in December 1859 and reported the event for the Toledo Blade. A Freemason, he belonged to Toledo Lodge No. 144. As the year 1858 ended, Ashley was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives for the 36th Congress, taking office on March 4, 1859, and thereby beginning a decade of influential congressional service during the nation’s gravest constitutional crisis.

Ashley served in the United States House of Representatives from March 4, 1859, through March 3, 1869, participating actively in the democratic process and representing the interests of his Ohio constituents during the 36th through 40th Congresses. During the American Civil War he strongly supported the Union cause, helping recruit troops for the Union Army and emerging as a leader among the Radical Republicans. As chairman of the powerful Committee on Territories, he played a central role in shaping the map of the American West, being instrumental in the creation, naming, and boundary definition of the Territories of Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, and Washington, and authoring the Arizona Organic Act. At the same time, he opposed the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and especially the practice of polygamy, and he worked to limit Utah’s territorial boundaries in an effort to curb Mormon political influence.

Ashley’s most enduring national legacy lies in his antislavery legislative work. In 1862 he authored a bill to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia. The following year, in 1863, he introduced a measure to amend the Constitution to end slavery throughout the United States. As House majority floor manager for the proposal that became the Thirteenth Amendment, he guided the measure through intense debate to final passage in the House of Representatives on January 31, 1865, when it secured the required two‑thirds majority by a margin of just two votes. The amendment was later ratified by the states as the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, formally abolishing slavery in the United States. Ashley also became a central figure in the movement to impeach President Andrew Johnson. Deeply suspicious of Johnson’s conduct and motives, he even suspected the president of complicity in Abraham Lincoln’s assassination and denounced him as a “loathing incubus which has blotted our country’s history.” Outraged by Johnson’s vetoes of legislation extending the Freedmen’s Bureau, the Civil Rights Act, and the Reconstruction Acts, and by what he saw as Johnson’s alliance with southern oligarchs, Ashley authored the resolution of January 7, 1867, that launched the first impeachment inquiry against Johnson. Although the House initially voted down impeachment on December 7, 1867, it reversed course in February 1868 and voted to impeach; Johnson was ultimately acquitted in the Senate trial.

Ashley’s radical views on race and Reconstruction, including his support for educational qualifications for voting and his uncompromising stance on equal rights, alienated some voters in his district. In the 1868 election he was narrowly defeated by Democrat Truman Hoag by fewer than 1,000 votes, a loss that nearly bankrupted him and ended his decade in Congress on March 3, 1869. Nonetheless, his party recognized his service: President Ulysses S. Grant appointed him Governor of the Montana Territory in 1869. Ashley’s tenure there, lasting about fifteen months until his removal in 1870, was marked by efforts to promote public education, including for Chinese immigrants, and by controversial political appointments. These policies proved unpopular in the largely Democratic territory, contributing to his dismissal. After leaving Montana, Ashley returned to Toledo and turned his energies to railroad development, working to link Toledo with northern Michigan and the Ann Arbor–Detroit region. He helped build the Ann Arbor Railroad and served as its president from 1877, when he moved to Ann Arbor, Michigan, while two of his sons attended the University of Michigan Law School, until 1890, when his sons assumed control. Although the railroad later went bankrupt during the financial crisis of 1893, it continued to operate in various forms thereafter. Ashley made unsuccessful bids to return to Congress from Ohio in 1890 and 1892.

Ashley suffered from diabetes from at least 1863 and endured chronic health problems in his later years. On September 16, 1896, after a fishing trip near Alma, Michigan, he died of heart failure and was interred in Woodlawn Cemetery in Toledo, Ohio. His contemporaries and later observers offered sharply divergent assessments of his character and abilities. Civil rights leader Frederick Douglass regarded him as one of the few white men determined to secure equal justice for all, grouping him with Benjamin Wade, Thaddeus Stevens, and Charles Sumner, while Mary C. Ames described him as the most genial and kind man in Congress. A eulogy at the Unitarian Church in Ann Arbor praised his large stature “intellectually, physically and morally,” noting that “there was nothing petty, small or mean about him.” Some historians and contemporaries, however, were critical: C. Vann Woodward called him “a nut with an idée fixe,” Eric McKitrick described him as possessing “an occult mixture of superstition and lunacy,” and journalist Benjamin Perley Poore dismissed him as a man “of the lightest mental calibre and most insufficient capacity.” Yet Ashley’s contributions to emancipation and Reconstruction have drawn renewed scholarly attention, including works such as Rebecca E. Zietlow’s The Forgotten Emancipator (2018) and Robert F. Horowitz’s Great Impeacher (1979). His efforts on behalf of racial equality were formally recognized three years before his death by the Afro‑American League of Tennessee, and he donated the proceeds of a volume of his speeches to support the construction of schools. His legacy endures in public memory: a street leading to the railroad depot in downtown Ann Arbor, Michigan, bears his name; his descendant James Ashley IV completed a portrait of him now installed in the LaValley Law Library at the University of Toledo College of Law; and in early 2010 the Ohio Historical Society proposed him as a finalist in a statewide vote for inclusion in the National Statuary Hall Collection at the United States Capitol. In popular culture, he was portrayed by actor David Costabile in Steven Spielberg’s 2012 film Lincoln, reflecting his central role in the struggle to secure the Thirteenth Amendment.