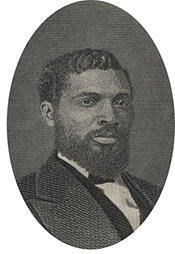

Representative James Thomas Rapier

Here you will find contact information for Representative James Thomas Rapier, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | James Thomas Rapier |

| Position | Representative |

| State | Alabama |

| District | 2 |

| Party | Republican |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | December 1, 1873 |

| Term End | March 3, 1875 |

| Terms Served | 1 |

| Born | November 13, 1837 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | R000064 |

About Representative James Thomas Rapier

James Thomas Rapier (November 13, 1837 – May 31, 1883) was an American lawyer, planter, and Republican politician from Alabama during the Reconstruction Era. He served as a United States Representative from Alabama for one term, from March 4, 1873, to March 3, 1875, representing the state’s 2nd congressional district. A nationally prominent figure in the Republican Party and one of seven African American members of the Forty-third Congress, he played a notable role in debates over civil rights and federal support for education and land for freedpeople.

Rapier was born free in 1837 in Florence, Alabama, to John H. Rapier, a prosperous local barber, and his wife, both members of an established community of free people of color. His father had been emancipated in 1829, and his mother came from a free Black family in Baltimore, Maryland. Rapier had three older brothers. His mother died in 1841 when he was four years old. In 1842, he and his brother John Jr. were sent to Nashville, Tennessee, to live with their paternal grandmother, Sally Thomas. There they attended a school for African American children, where they learned to read and write at a time when educational opportunities for Black southerners were severely restricted.

In 1856 Rapier traveled to Canada with his uncle Henry Thomas, his father’s half-brother, who settled in Buxton, Ontario, an all-Black community largely composed of formerly enslaved African Americans who had escaped to Canada via the Underground Railroad. The settlement, developed with the aid of Rev. William King, a Scots-American Presbyterian missionary, offered a relatively secure environment for Black education and landownership. Rapier attended the Buxton Mission School, which was highly regarded for its classical curriculum. That same year he earned a teaching degree at a normal school in Toronto. Seeking further education, he then traveled to Scotland to study at the University of Glasgow. Returning to North America, he completed legal studies at Montreal College, earned a law degree, and was later admitted to the bar in Tennessee.

After completing his education, Rapier taught for a time at the Buxton Mission School before returning to the United States. In 1864 he moved to Nashville, Tennessee, where he worked as a reporter for a northern newspaper. He purchased 200 acres in Maury County, Tennessee, and became a cotton planter, entering the post–Civil War southern economy as a Black landowner. Rapier emerged as an advocate for African American political rights, making a keynote speech at the Tennessee Negro Suffrage Convention and pressing for Black voting rights. He was dismayed by the rapid return of former Confederates to positions of power in state government, which he believed threatened the gains of emancipation and Reconstruction.

With his father in need of assistance, Rapier returned to Alabama in 1866 and settled again in his native state. He purchased 550 acres of land and resumed cotton cultivation, becoming part of a small but significant class of Black planters in the Reconstruction South. Rapier quickly became active in Republican politics. In 1867 he served as a delegate to the Alabama state constitutional convention, a key gathering that helped reshape the state’s legal and political framework after the Civil War. In 1870 he ran unsuccessfully for the office of Alabama Secretary of State. During these years he also became involved in efforts to organize Black labor and to secure better conditions and political representation for African American workers.

In 1872 Rapier was elected as a Republican to the Forty-third Congress from Alabama’s 2nd congressional district, one of three African American congressmen elected from Alabama during Reconstruction. He served in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1873 to 1875. As a member of Congress, Rapier represented his constituents during a critical period in American history, participating in the legislative process as the nation struggled over the meaning of freedom and citizenship in the postwar South. He proposed the creation of a federal land bureau to allocate Western lands to freedmen, reflecting his belief that landownership was essential to genuine freedom. He also urged Congress to appropriate $5 million for public education in Southern schools, arguing that federal support for education was necessary to uplift both Black and white citizens in the former Confederate states.

Rapier’s congressional service coincided with the final phase of federal Reconstruction policy, and he became a leading advocate for national civil rights legislation. In 1874 he worked for passage of what became the Civil Rights Act of 1875, which guaranteed equal access to public accommodations such as inns, theaters, and public conveyances. Along with the other six Black members of the Forty-third Congress, he testified in support of the measure. Rapier recounted his own experiences of racial discrimination, including being denied service at every inn along the route between Montgomery, Alabama, and Washington, D.C., despite his status as a United States Congressman. In his arguments he drew comparisons between racial distinctions in the United States and class and religious hierarchies abroad, observing that in Europe “they have princes, dukes, and lords,” in India “brahmans or priests, who rank above the sudras or laborers,” while in America “our distinction is color.” He described himself as “half slave and half free,” possessing political rights but lacking full civil rights. The Civil Rights Act of 1875, which he had strongly supported, was later declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1883. It was the last federal civil rights statute enacted until the Civil Rights Act of 1957; key elements of its guarantees were not restored until the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Civil Rights Act of 1968.

After losing his bid for reelection in 1874, Rapier remained active in public service and Republican politics. He was appointed by the Republican presidential administration as a collector for the Internal Revenue Service in Alabama, a federal position he held until his death. From this post he continued to campaign against the conservative Democratic Redeemer government that was consolidating power in Alabama. Despite the efforts of Rapier and other Reconstruction leaders, Democrats regained control of the state legislature in 1874 and, over the ensuing decades, enacted increasingly restrictive laws that laid the foundation for Jim Crow segregation. These measures culminated in the Alabama constitution of 1901, which imposed poll taxes, literacy tests, and other devices that effectively disenfranchised most Black citizens and many poor whites, excluding them from the political system well into the twentieth century.

James Thomas Rapier died in Montgomery, Alabama, on May 31, 1883, of pulmonary tuberculosis. He was buried in Calvary Cemetery in St. Louis, Missouri. His papers and family correspondence, preserved as the Rapier Family Papers, are held by Howard University and have served as important sources for historians studying Reconstruction, Black political leadership, and civil rights advocacy in the nineteenth century. Later scholarship, notably by historian John Hope Franklin, has challenged earlier portrayals of Rapier—such as those by Walter L. Fleming of the Dunning School—that mischaracterized him as a “carpetbagger” from Canada. Franklin and others have emphasized Rapier’s Alabama origins, his extensive education in Canada and Scotland, and his deep engagement with Southern politics as evidence of his rootedness in the region and his significance as a Black leader in Reconstruction-era Alabama.