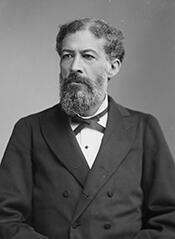

Representative John Mercer Langston

Here you will find contact information for Representative John Mercer Langston, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | John Mercer Langston |

| Position | Representative |

| State | Virginia |

| District | 4 |

| Party | Republican |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | December 2, 1889 |

| Term End | March 3, 1891 |

| Terms Served | 1 |

| Born | December 14, 1829 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | L000074 |

About Representative John Mercer Langston

John Mercer Langston (December 14, 1829 – November 15, 1897) was an African-American abolitionist, attorney, educator, activist, diplomat, and politician who became one of the most prominent Black leaders of the nineteenth century. Born free in Louisa County, Virginia, he was the son of a freedwoman of mixed African and Native American ancestry and a white English immigrant planter. Orphaned at a young age, he was taken to Ohio, where he was raised and educated in a free state. Together with his older brothers Gideon and Charles Henry Langston, he became active early in the abolitionist movement, helping refugee slaves escape to the North along the Ohio segment of the Underground Railroad. The Langston brothers were closely connected to later African-American cultural history: they were, respectively, the grandfather and great-uncle of the renowned poet James Mercer Langston Hughes, better known as Langston Hughes.

Langston received his early education in Ohio and attended Oberlin College, one of the few institutions of higher learning at the time that admitted Black students. He earned a bachelor’s degree from Oberlin in 1849 and a master’s degree in theology in 1852. Denied admission to law schools because of his race, he read law under established attorneys in Ohio and was admitted to the bar in 1854, becoming one of the first African-American lawyers in the state. In 1855 he was elected town clerk of Brownhelm Township, Ohio, making him one of the first African Americans in the United States elected to public office. By the late 1850s he had emerged as a leading antislavery figure in the region, serving with his brother Charles in the Ohio Anti-Slavery Society—John as president, traveling widely to organize local units, and Charles as executive secretary in Cleveland. He played a key role in the Oberlin–Wellington Rescue of 1858, an episode in which abolitionists forcibly freed a captured fugitive slave, an event that drew national attention to the antislavery cause.

During the Civil War era, Langston expanded his leadership on behalf of African-American rights. In 1863, after the federal government authorized the creation of the United States Colored Troops, he was appointed to recruit Black soldiers for the Union Army. He enlisted hundreds of men for the Massachusetts 54th and 55th regiments, as well as approximately 800 men for Ohio’s first Black regiment. Even before the war ended, he advocated forcefully for Black suffrage, arguing that African Americans’ military service had earned them the right to vote and that the franchise was essential to achieving equality. In 1864 he chaired the committee that drafted the agenda for the black National Convention, which called for the abolition of slavery, racial unity and self-help, and equality before the law. To advance these aims, the convention founded the National Equal Rights League and elected Langston as its first president; he served in that role until 1868, traveling extensively to build state and local auxiliaries across the country.

After the Civil War, Langston entered federal service during Reconstruction. He was appointed inspector general for the Freedmen’s Bureau, the federal agency charged with assisting formerly enslaved people and overseeing labor contracts in the former Confederate states. In this capacity he inspected conditions in the South, supported the establishment of schools for freedmen and their children, and worked to protect the civil and economic rights of newly freed African Americans. In 1868 he moved to Washington, D.C., where he became the founding dean of the law department at Howard University, creating what was effectively the first Black law school in the United States. He helped design the curriculum, recruited faculty and students, and worked to establish rigorous academic standards while fostering an open intellectual environment reminiscent of Oberlin. He later served as acting president of Howard University in 1872 and as vice president of the institution, although he was ultimately passed over for the permanent presidency, a decision the selection committee declined to explain.

Langston also played a role in national civil rights legislation and public health administration during the Reconstruction period. In 1870 he assisted Republican Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts in drafting the civil rights bill that became the Civil Rights Act of 1875, which was passed by the 43rd Congress in February 1875 and signed into law by President Ulysses S. Grant on March 1, 1875. President Grant also appointed Langston to the Board of Health of the District of Columbia, where he participated in efforts to improve public health and sanitation in the rapidly growing capital. His national stature as a Republican leader and advocate for African-American rights continued to grow, and in 1877 President Rutherford B. Hayes appointed him United States Minister Resident and Consul General to Haiti; he also served concurrently as chargé d’affaires to the Dominican Republic. During his diplomatic tenure he confronted frequent political unrest in Haiti, refusing to aid defeated factions in order to reduce tensions, and worked to strengthen ties between Haitians and African Americans.

In 1885 Langston returned to the United States and to his native Virginia, where he was appointed by the state legislature as the first president of Virginia Normal and Collegiate Institute at Petersburg, a historically Black land-grant college that later became Virginia State University. In this role he organized the new institution, recruited faculty, and helped shape its mission of higher education for African Americans in the post-Reconstruction South. At the same time, he began building a political base in Virginia. A member of the Republican Party, he ran for Congress in the hotly contested election of 1888 from Virginia’s Fourth Congressional District. After an extended dispute over election returns and charges of fraud, he was ultimately declared the winner and took his seat in the U.S. House of Representatives on September 23, 1890. Langston served as a Representative from Virginia in the United States Congress from 1889 to 1891, completing one term in office. He was the first Representative of color from Virginia and one of only five African Americans elected to Congress from the South during the late nineteenth-century Jim Crow era, before Southern states adopted new constitutions and electoral rules between 1890 and 1908 that effectively disenfranchised Black voters. During his service in the House of Representatives, he participated in the legislative process and represented the interests of his constituents at a time of mounting racial retrenchment.

Langston’s congressional tenure occurred during a significant period in American history, as Reconstruction had ended and Southern states were moving rapidly to curtail African-American political participation. His presence in Congress underscored both the achievements and the fragility of Black political power in the postwar South. After his term ended in March 1891, no African Americans would be elected to Congress from the South until 1973, following the enactment and enforcement of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which restored federal protection for Black voting rights. In addition to his public service, Langston contributed to African-American intellectual and political thought through his writings and speeches. He authored From the Virginia Plantation to the National Capitol; Or, the First and Only Negro Representative in Congress From the Old Dominion, published in 1894 by the American Publishing Company, an autobiographical work that traced his life from slavery-era Virginia to national office. A collection of his orations, Freedom and Citizenship: Selected Lectures of Hon. John Mercer Langston, originally delivered in the 1880s, was later republished in 2007.

In his later years, Langston remained an influential lecturer and advocate for civil rights, education, and Black political participation. He continued to speak across the country on issues of freedom, citizenship, and equality before the law. He died on November 15, 1897, in Washington, D.C. His legacy has been widely commemorated. The John Mercer Langston House in Oberlin, Ohio, where he lived during his early career, has been designated a National Historic Landmark. The town of Langston, Oklahoma, founded in 1890 as an all-Black town, was named in his honor, and its historically Black college, established in 1897 as the Oklahoma Colored Agricultural and Normal University, was renamed Langston University in 1941. Numerous schools have borne his name, including Langston High School in Johnson City, Tennessee (established in 1893), John M. Langston High School in Danville, Virginia, and Langston High School in Hot Springs, Arkansas, whose alumni included professional football player Ike Thomas, civil rights activist Mamie Phipps Clark, and physician Edith Mae Irby Jones. John Mercer Langston Elementary School at 33 P Street NW in Washington, D.C., opened in 1902 as a school for Black students and operated until 1993; the building later briefly served as a homeless shelter. Langston Golf Course in Washington, D.C., also commemorates his name. On July 17, 2021, the Arlington County, Virginia, County Board voted to rename its portion of U.S. Route 29, previously known as Lee Highway, after John M. Langston, joining an elementary school and community center on that route that already honored him.