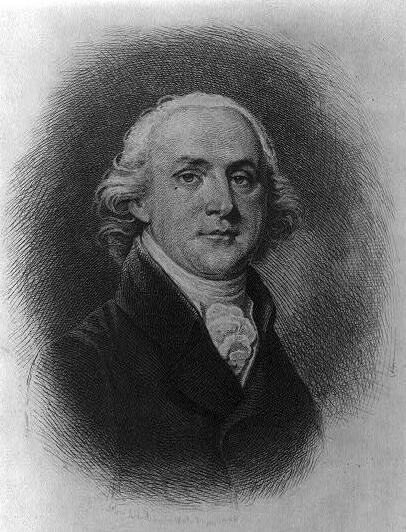

Representative John Francis Mercer

Here you will find contact information for Representative John Francis Mercer, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | John Francis Mercer |

| Position | Representative |

| State | Maryland |

| District | 2 |

| Party | Unknown |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | October 24, 1791 |

| Term End | March 3, 1795 |

| Terms Served | 2 |

| Born | May 17, 1759 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | M000645 |

About Representative John Francis Mercer

John Francis Mercer (May 17, 1759 – August 30, 1821) was a Founding Father of the United States, politician, lawyer, planter, and slave owner from Virginia and Maryland who served as a Representative from Maryland in the United States Congress from 1791 to 1795. An officer during the Revolutionary War, he initially served in the Virginia House of Delegates and later in the Maryland State Assembly. As a member of the Maryland legislature, he was appointed a delegate to the Philadelphia Convention of 1787, where he took part in framing the U.S. Constitution, although he left the convention before signing. Mercer was subsequently elected to the U.S. House of Representatives from two different districts in Maryland, and from 1801 to 1803 he served as the tenth governor of Maryland.

Mercer was born in 1759 at the Marlborough plantation in Stafford County in the Colony of Virginia, into a prominent legal and planter family. He was the son of John Mercer (1704–1768), a noted lawyer, planter, and investor in western lands, and his second wife Ann Roy (1729–1770), daughter of Dr. Mungo Roy of Essex County, Virginia. His father had nineteen children by two wives, though many did not survive to adulthood. From his father’s first marriage to Catherine Mason (1707–1750), daughter of burgess George Mason II, Mercer had several half-siblings who were influential in Virginia public life. His half-brother Captain John Fenton Mercer (1735–1756) was killed and scalped in western Virginia during the French and Indian War. Half-brothers George Mercer (1733–1784) and James Mercer (1736–1793) served in the Virginia House of Burgesses; James Mercer also became a prominent lawyer, a delegate to Virginia’s revolutionary conventions, a member of the Virginia House of Delegates and the Continental Congress (1779–1780), and later a judge on what became the Virginia Supreme Court. Among his sisters and half-sisters who reached adulthood were Sarah Mercer (1738–1806), who married Colonel Samuel Selden of Stafford County; Mary Mercer (1740–1764), who married Daniel McCarty Jr. of Westmoreland County; Grace Mercer (1751–1814), who married Muscoe Garnett of Essex County; Anna Mercer (1760–1787), who married Benjamin Harrison VI; and Maria Mercer (born 1761), who married Richard Brooke of King and Queen County. His younger brother Robert Mercer (1764–1800) married Mildred Carter, daughter of prominent planter Landon Carter, and became a lawyer and editor of the Genius of Liberty. Like his brothers who survived to adulthood, John Francis Mercer attended the College of William and Mary, from which he graduated in 1775, and he read law under Thomas Jefferson.

During the American Revolutionary War, Mercer entered military service as a lieutenant in the 3rd Virginia Regiment of the Continental Army. He was promoted retroactively to captain as of June 1777 and was wounded at the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777. On June 8, 1778, he became aide-de-camp, with the rank of major, to General Charles Lee. When Lee retired from the army in July 1779, Mercer resigned his commission. By October 1779, however, he had recruited a cavalry company for the Virginia militia as British forces and associated raiders threatened plantations along the Chesapeake Bay. In this capacity he held the rank of lieutenant colonel and served briefly under the Marquis de Lafayette, taking part in operations that included the Battle of Guilford, the Battle of Green Spring, the siege of Yorktown, and other engagements in the southern theater.

Following the surrender of General Cornwallis at Yorktown in 1781, Mercer entered public life in Virginia. Stafford County voters elected him as one of their two representatives in the Virginia House of Delegates in 1782, where he served alongside Charles Carter. The legislature selected him as one of Virginia’s delegates to the Continental Congress in 1783 and again in 1784. After the death of Richard Brent, a special election was held to fill Brent’s seat as Stafford County’s delegate to the House of Delegates, and Mercer was chosen to complete the remainder of the session. In 1785 he married Sophia Sprigg (1766–1812), an heiress of Anne Arundel County, Maryland, and soon afterward he moved from Virginia to Maryland, where he began to manage and expand his wife’s estates.

In Maryland, Mercer became a substantial planter and slave owner while continuing his legal and political career. His wife Sophia Sprigg, daughter of Richard Sprigg (1739–1798) and Margaret Marcer, née Caile (1745–1796), had inherited land and enslaved people under her grandparents’ wills, including five enslaved persons from her grandfather in 1782 and nineteen from her grandmother in 1789. Mercer brought twenty-four enslaved people from Virginia to Anne Arundel County in 1798–1799 and another eleven between 1799 and 1801, including at least three inherited from his mother. He operated the “West River Farm” and other properties using enslaved labor. In 1810 he sold his slaves and plantation equipment in Anne Arundel County to his namesake son John, which, together with gaps in surviving records, makes the precise number of enslaved people he held in 1810 and 1820 uncertain. By the time of his death in 1821, Mercer owned seventy-two enslaved people, and his personal property, including enslaved persons, was valued at $19,976.75. While residing in Maryland, he was chosen as one of the state’s delegates to the Philadelphia Convention in 1787. There he participated in the debates over the proposed federal Constitution but, being strongly opposed to what he regarded as excessive centralization of power, he withdrew before the document was completed and did not sign. He also represented fellow anti-ratification leader George Mason as a private attorney in collecting debts owed by Maryland residents. Mercer later served as a delegate to the Maryland State Convention of 1788, which considered the ratification of the Constitution, and he sat in the lower house of the Maryland State Assembly in 1788–1789 and again in 1791–1792.

Mercer’s national legislative career began with his service in the United States House of Representatives. He was an unsuccessful candidate to represent Maryland’s 3rd congressional district in the first federal elections of 1789, but he was later elected to that district in 1792 and then to Maryland’s 2nd district in 1793. He served in the House of Representatives from 1791 to 1795, completing two terms in Congress during a formative period in the federal government’s development. During this time he contributed to the legislative process and represented the interests of his Maryland constituents. Although often associated with Anti-Federalist and later Jeffersonian Republican positions, his party affiliation in early records is sometimes listed as unknown. Notably, despite being a slave owner, Mercer was one of only seven representatives to vote against the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, which strengthened the legal mechanisms for the recapture of escaped enslaved people. He resigned his seat in the House on April 13, 1794, but remained active in Maryland politics and public affairs.

After leaving Congress, Mercer continued to serve in the Maryland House of Delegates in 1800–1801 and was elected the tenth governor of Maryland, holding office for two one-year terms from 1801 to 1803. As governor, he presided over state affairs during the early years of Thomas Jefferson’s presidency and the consolidation of Republican power, though he himself later aligned with Federalists during Jefferson’s administration. Following his governorship, Mercer again served in the Maryland House of Delegates from 1803 to 1806. Illness increasingly affected him in his later years, limiting his public activity but not entirely removing him from political life and plantation management.

Mercer’s marriage to Sophia Sprigg produced at least four children. Their daughter Margaret Mercer became known for her abolitionist views and, in contrast to her father’s lifelong slaveholding, freed all the enslaved people she inherited upon his death. Their son John Mercer (1788–1848) purchased enslaved people and plantation equipment from his father in 1810 and, in 1818, received part of his maternal inheritance when his father released his life interest in 606 acres of the 1,478 acres that Sophia had re-patented in 1804; this John Mercer later married Mary Swann of Alexandria, Virginia, and died in Virginia. Another son, Richard Mercer (by 1789–1821), died without issue. Through his extended family, John Francis Mercer was also connected to later antislavery efforts: his nephew Charles Fenton Mercer served in Congress, opposed slavery, and became president of the American Colonization Society, which advocated the resettlement of freed African Americans in Africa.

In declining health, Mercer traveled to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to seek medical treatment and died there on August 30, 1821. A funeral service was held at St. Peter’s Church in Philadelphia. Contemporary and later accounts differ as to whether his remains were interred in the churchyard at St. Peter’s or returned to his “Cedar Park” estate in Maryland for burial.