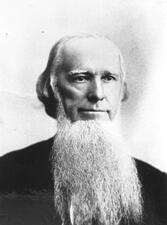

Senator Joseph Emerson Brown

Here you will find contact information for Senator Joseph Emerson Brown, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | Joseph Emerson Brown |

| Position | Senator |

| State | Georgia |

| Party | Democratic |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | January 1, 1880 |

| Term End | March 3, 1891 |

| Terms Served | 2 |

| Born | April 15, 1821 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | B000936 |

About Senator Joseph Emerson Brown

Joseph Emerson Brown (April 15, 1821 – November 30, 1894), often referred to as Joe Brown, was an American attorney, jurist, businessman, and politician who became one of the most influential public figures in nineteenth-century Georgia. A member of the Democratic Party for most of his career, he served as the 42nd Governor of Georgia from 1857 to 1865, the only governor of the state to serve four consecutive terms, and later represented Georgia in the United States Senate from 1879 to 1891. His senatorial service, which in other sources is often dated from 1880 to 1891, encompassed two terms during a significant period in American history, when he participated in the legislative process and represented the interests of his Georgia constituents in the post-Reconstruction era.

Brown was born on April 15, 1821, in Pickens District, South Carolina, into a modest farming family of limited means. As a youth he moved with his family to the Cherokee frontier region of Georgia, settling in what would become Cherokee County. Largely self-educated in his early years, he worked on the family farm and taught school to support himself while pursuing further learning. His early experiences in the upcountry frontier environment, combined with exposure to evangelical Protestantism and Jacksonian-era politics, helped shape his strong belief in states’ rights and local autonomy, views that would later define his political career.

Determined to obtain a formal education, Brown studied at local academies and then attended Yale Law School in New Haven, Connecticut, where he received legal training that distinguished him among many Southern contemporaries. After his return to Georgia, he was admitted to the bar and established a law practice in Canton, Georgia. His legal ability and political acumen quickly brought him to public attention. Initially a member of the Whig Party, he served in the Georgia state senate and as a circuit judge of the superior court. As the Whig Party collapsed in the 1850s, Brown aligned himself with the Democratic Party, positioning himself as a champion of small farmers and the white yeomanry of the hill country, which helped propel his rapid rise in state politics.

In 1857 Brown was elected Governor of Georgia, beginning the first of four consecutive two-year terms that lasted until 1865. A firm believer in slavery and Southern states’ rights, he became a leading secessionist in 1861 and played a central role in taking Georgia out of the Union and into the Confederacy. As governor during the American Civil War, he strongly supported secession but frequently defied the Confederate government’s wartime policies. He resisted the Confederate military draft, insisting that Georgia’s local troops should be used only for the defense of the state, and he denounced Confederate President Jefferson Davis as an incipient tyrant. Brown challenged Confederate impressment of animals and goods to supply the troops, and opposed the impressment of enslaved laborers to work in military encampments and on defensive lines. His stance inspired several other Southern governors to adopt similarly defiant positions. After the loss of Atlanta in 1864, Brown withdrew the state’s militia from Confederate forces so they could harvest crops for Georgia and the army, and when Union troops under General William T. Sherman overran much of Georgia later that year, he called for an end to the war.

Following the Confederacy’s defeat, Brown’s political course shifted markedly. After the American Civil War, he joined the Republican Party for a time and cooperated with federal Reconstruction authorities. In 1865 he was appointed chief justice of the Supreme Court of Georgia, a position he held until 1870. His tenure on the bench coincided with the turbulent early Reconstruction period, during which he participated in efforts to reestablish civil government and legal order in the state. His alignment with the Republicans and acceptance of Reconstruction policies made him a controversial figure among many white Georgians, but it also positioned him as a key intermediary between federal authorities and the state.

By the early 1870s Brown had rejoined the Democratic Party and turned his attention increasingly to business. He became president of the state-owned Western and Atlantic Railroad, a powerful and lucrative position that enabled him to amass substantial wealth; by 1880 he was widely estimated to be a millionaire. Brown invested heavily in coal and iron enterprises in northwestern Georgia, particularly in Dade County, where he benefited from the convict leasing system. He obtained convicts leased from state, county, and local governments to work in his coal mining operations, a practice that later drew significant criticism. His Dade Coal Company gradually absorbed other coal and iron companies, and by 1889 his holdings were consolidated under the name Georgia Mining, Manufacturing and Investment Company. During the 1870s he also played a notable philanthropic role in Southern religious life by rescuing the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary from financial distress; in recognition, the seminary established the Joseph Emerson Brown Chair of Christian Theology in his honor, a chair that was vacated in 2020 because of his support for slavery and his use of convict leasing.

Brown’s return to partisan Democratic politics culminated in his selection for national office. He was twice elected by the Georgia state legislature as a United States Senator, serving from 1879 to 1891, a period sometimes cited as 1880 to 1891 in contemporary accounts. As a Democratic senator from Georgia, he served two terms during a transformative era marked by the end of Reconstruction, the rise of the New South, and the entrenchment of Jim Crow. In the Senate, Brown contributed to the legislative process and advocated for the economic and political interests of his state, including railroad development and industrial expansion, while supporting the broader Democratic program of limited federal government and states’ rights. During this time he was a central figure in the so‑called Bourbon Triumvirate, alongside fellow Georgia leaders John Brown Gordon and Alfred H. Colquitt, a powerful alliance that dominated Georgia politics in the late nineteenth century and promoted conservative fiscal policies, white supremacy, and reconciliation with the North on terms favorable to Southern elites.

In his later years Brown remained a prominent public figure in Georgia, combining his roles as businessman, party leader, and elder statesman. His influence extended into the next generation: his son, Joseph Mackey Brown, would also serve twice as governor of Georgia in the early twentieth century. Brown’s name and legacy became embedded in the state’s landscape and institutions. Joseph E. Brown Hall on the campus of the University of Georgia in Athens, completed in 1932, was named in his honor, as were Joseph Emerson Brown Park in Marietta, Georgia, and the city of Emerson, Georgia, which references his middle name. These commemorations reflected both his long tenure in public office and his role in shaping Georgia’s political and economic development.

Joseph E. Brown died on November 30, 1894, in Atlanta, Georgia. He was honored by lying in state in the Georgia State Capitol, a recognition of his decades of service as governor, jurist, businessman, and United States senator. He was buried in Oakland Cemetery in Atlanta, where his tombstone remains a notable monument. In 1928 a memorial statue of Brown and his wife was installed on the grounds of the State Capitol, further cementing his place in the state’s public memory. His career, marked by ardent defense of slavery and states’ rights, resistance to Confederate centralization, postwar collaboration and then renewed Democratic dominance, and extensive use of convict labor in private enterprise, has continued to be the subject of historical scrutiny and reassessment.