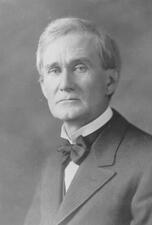

Senator Lawrence Yates Sherman

Here you will find contact information for Senator Lawrence Yates Sherman, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | Lawrence Yates Sherman |

| Position | Senator |

| State | Illinois |

| Party | Republican |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | April 7, 1913 |

| Term End | March 3, 1921 |

| Terms Served | 2 |

| Born | November 8, 1858 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | S000348 |

About Senator Lawrence Yates Sherman

Lawrence Yates Sherman (November 8, 1858 – September 15, 1939) was a Republican politician from Illinois who served as a United States Senator, the 28th Lieutenant Governor of Illinois, and Speaker of the Illinois House of Representatives. He is best known nationally for his leading role in preventing the ratification of the Treaty of Versailles, thereby helping to keep the United States out of the League of Nations. His service in the United States Senate, from 1913 to 1921, spanned a significant period in American history that included World War I and the postwar peace negotiations.

Sherman was born on November 8, 1858, near Piqua in Miami County, Ohio, the son of Nelson Sherman and Maria (Yates) Sherman. In 1859, when he was about a year old, he moved with his parents to McDonough County, Illinois, and about eight years later the family relocated to Grove Township in Jasper County, Illinois. He attended the common schools and later studied at Lee’s Academy in Coles County. Pursuing a legal education, he enrolled at McKendree University in Lebanon, Illinois, where he earned an LL.B. degree in 1882. Sherman studied law under Judge Henry Horner and Professor Samuel H. Deneen, and in 1882 he was admitted to the bar in Illinois, beginning a legal and political career that would keep him prominent in state and national affairs for decades.

After his admission to the bar, Sherman quickly became involved in Illinois local government and politics. He served as city attorney for Macomb, Illinois, from 1885 to 1887, and simultaneously held judicial office as a McDonough County judge from 1886 to 1890. In 1890, he entered private practice in Macomb, building a reputation as a capable lawyer and public servant. Sherman’s personal life during these years included two brief marriages: in 1891 he married Ella M. Crews, who died in 1893, and on March 4, 1908, he married Estelle Spitler, who died in 1910.

Sherman’s state legislative career began with his election to the Illinois House of Representatives, where he served four terms from 1897 to 1905. During his second term, in 1899, he was chosen as the 40th Speaker of the Illinois House, and in 1901 he became the second Republican, and the fifth person overall, to serve two terms as Speaker. In that capacity he played an important role in the creation of Western Illinois State Normal School (now Western Illinois University) and was instrumental in securing Macomb as its location. In recognition of his efforts, the main administrative building at Western Illinois University was renamed Sherman Hall in 1957. In 1904, Sherman sought higher office with an unsuccessful bid for Governor of Illinois, but he was nominated that year for Lieutenant Governor and was elected, becoming the 28th Lieutenant Governor of Illinois and serving from 1905 to 1909. As lieutenant governor, he was ex officio president of the Illinois Senate, further solidifying his influence in state government.

After his term as lieutenant governor, Sherman remained active in public affairs. In 1909 he ran for mayor of Springfield, Illinois, but lost by approximately 300 votes. That same year he was appointed president of the Illinois state board of administration for public charities, a position he held from 1909 to 1913, overseeing aspects of the state’s charitable and institutional systems before returning to the practice of law in Springfield. On the national stage, he was a delegate to the 1912 Republican National Convention, where he supported Theodore Roosevelt but then worked to prevent the party split that ultimately produced the Progressive “Bull Moose” Party. After the split occurred, he supported the Republican nominee, President William Howard Taft, in the general election.

Sherman’s entry into the United States Senate came through the complex politics of Illinois in 1912. That year he entered the Republican “advisory” primary for the U.S. Senate, challenging five-term incumbent Senator Shelby M. Cullom, who had been weakened politically by his support for Senator William Lorimer, then embroiled in a bribery scandal over his 1909 Senate election. In the April 9, 1912 primary, Sherman defeated Cullom by about 60,000 votes, prompting Cullom to withdraw his name from consideration by the Illinois General Assembly, which at that time still elected senators. Three months later, the United States Senate invalidated Lorimer’s election and declared his seat vacant. Illinois Attorney General William H. Stead ruled that because the General Assembly had failed to properly elect Lorimer in 1909, the governor could not appoint a replacement, leaving the legislature with two Senate seats to fill. In the November 1912 elections, Republicans lost control of the state due to the Republican–Progressive split, and although Democrats held a plurality in the General Assembly, they lacked a majority. After prolonged deadlock, a compromise arranged by Governor Edward F. Dunne led, on March 26, 1913, to the election of Democrat J. Hamilton Lewis to fill the Cullom seat and of Sherman to fill the remaining two years of Lorimer’s term. In 1914, following ratification of the Seventeenth Amendment, which he had supported even before entering the Senate, Sherman was elected by popular vote to a full term, serving in the Senate from 1913 to 1921. During the Sixty-sixth Congress he was chairman of the Senate Committee on the District of Columbia. In 1916, facing deteriorating hearing that made it difficult for him to follow debate on the Senate floor, he decided not to seek reelection in 1920, effectively retiring from electoral politics at the close of his term.

Sherman’s Senate career coincided with World War I and the contentious debate over the postwar settlement, and he emerged as one of the leading “irreconcilables” or “bitter-enders” who opposed the Treaty of Versailles and American participation in the League of Nations. Historian Aaron Chandler and others have credited Sherman with playing a key role in the treaty’s defeat. He described the treaty as “humanitarian in purpose, but impracticable in operation,” and argued that the proposed League would be weak and would compromise American sovereignty. A nationalist but not an isolationist, Sherman favored close relations with Britain and France and was willing to accept limited obligations to America’s wartime allies, but he opposed any international arrangement that, in his view, allowed small or weaker nations to combine and dictate foreign policy to the United States, Great Britain, France, and Italy. He criticized provisions such as Article 7, which would have given the British Empire, counting its dominions and colonies, six votes in the League Assembly while the United States would have only one, warning that British diplomatic influence could easily secure a majority against American interests. He also expressed concern that the large number of predominantly Catholic nations in the League were influenced by the Vatican, which he believed could leave the United States beholden to the Pope in foreign affairs. Sherman further argued that League membership would make the United States a “perpetual taxpayer for the benefit of Europe,” contending that reconstruction costs would be apportioned by ability to pay and would fall heavily on American taxpayers.

Sherman objected not only to the League of Nations covenant but also to specific territorial and political provisions of the Treaty of Versailles. He sharply criticized the Shantung settlement, under which German concessions in China’s Shantung province were transferred to Japan rather than returned to China, declaring that “40,000,000 Chinese in Shantung were denied the right of self-determination and delivered to Japan under treaty.” He also regarded the territorial concessions to the newly reconstituted Poland as insufficient. In March 1919, he was one of thirty-nine senators who signed the “round-robin” resolution insisting that the peace treaty with Germany be separated from any proposal for a League of Nations and pledging to vote against the treaty in its existing form. During Senate consideration of amendments, after President Woodrow Wilson announced that he would not accept any changes, Sherman declared that he would vote for any pertinent amendment, remarking that “there could not be confusion worse confounded if every amendment offered here were voted into the treaty,” and concluding that after all amendments were adopted he would still vote to reject the entire treaty and League. When the treaty finally came to a vote with reservations attached, Sherman voted against it, as did Wilson’s supporters at the president’s urging. After its defeat, Sherman delivered an address he described as “a funeral oration over the defunct remains” of the treaty, noting that it was one of the rare occasions on which he found himself in agreement with Wilson.

Following the end of his Senate service in 1921, Sherman returned to the practice of law in Springfield, Illinois. In 1924 he moved to Daytona Beach, Florida, where he continued to practice law and entered the investment business. He helped organize the First National Bank of Daytona Beach and served as its president in 1925, subsequently becoming chairman of its board of directors from 1925 to 1927. After the bank merged with the Atlantic National Bank of Jacksonville in 1930, Sherman served as a director of the merged institution until his retirement. He withdrew from all active business pursuits in 1933. Lawrence Yates Sherman died in Daytona Beach on September 15, 1939, and was interred in Faunce Cemetery in Montrose, Illinois.