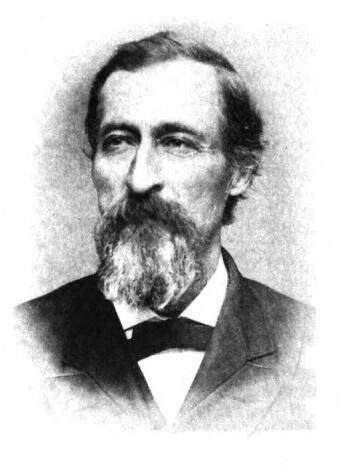

Representative Luman Hamlin Weller

Here you will find contact information for Representative Luman Hamlin Weller, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | Luman Hamlin Weller |

| Position | Representative |

| State | Iowa |

| District | 4 |

| Party | National Greenbacker |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | December 3, 1883 |

| Term End | March 3, 1885 |

| Terms Served | 1 |

| Born | August 24, 1833 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | W000275 |

About Representative Luman Hamlin Weller

Luman Hamlin Weller (August 24, 1833 – March 2, 1914) was a United States Greenback Party member who served a single term in the United States House of Representatives as the representative of Iowa’s 4th congressional district in the early 1880s. Born in Bridgewater, Connecticut, he attended public schools in New Britain, Connecticut, and pursued further studies at the Suffield Literary Institute in Suffield, Connecticut. He later moved west, where he worked variously as a farmer, justice of the peace, and private practice lawyer, occupations that grounded him in the concerns of rural communities and small producers that would shape his political outlook.

Weller’s early professional life combined agriculture, local public service, and the law. As a farmer, he experienced firsthand the economic pressures of high input costs and low commodity prices, conditions that would later inform his advocacy for monetary and tariff reform. His service as a justice of the peace and his work as a lawyer in private practice gave him familiarity with local governance and the legal system, and helped establish his reputation as a spokesman for agrarian and debtor interests. These experiences prepared him for political activity within the Greenback movement, which sought currency expansion and relief for farmers and laborers in the post–Civil War economy.

In 1882, Weller emerged as a significant figure in Iowa politics when he ran for Congress as a candidate of the National Greenback Party in Iowa’s 4th congressional district, a largely rural area in northeastern Iowa. In a notable upset, he defeated the sitting Republican congressman, Thomas Updegraff. His victory was aided by several unusual circumstances: redistricting in 1881 had forced Updegraff to run in a substantially altered district that included only four counties from his former constituency; the Democratic candidate withdrew from the race and threw his support to Weller; and a nationwide wave of anti-Republican sentiment in the 1882 elections cost the Republican Party control of the U.S. House of Representatives and roughly one-fifth of its seats. No other Greenback candidate won a seat in the Forty-eighth Congress, and Weller’s election depended heavily on Democratic support in his district, whose leaders endorsed his candidacy.

Weller served in Congress from March 4, 1883, to March 3, 1885, representing Iowa’s 4th congressional district. As a member of the National Greenback Party, he participated in the legislative process during a significant period in American political and economic history, representing the interests of his agrarian and reform-minded constituents. In recognition of the Democratic backing that had helped secure his election, he entered the Democratic caucus in the House and supported its candidate for Speaker. In return, he was assigned to the Committee on War Claims and the Committee on Agriculture. These assignments did not match his preference—he had hoped for a seat on the Committee on Banking and Currency, from which he intended to attack what he termed “the infamous national banking system”—but they nonetheless provided him a platform to advocate for farmers and rural interests.

During his congressional service, Weller became nationally known by the nickname “Calamity” Weller. Enemies and critics ascribed the name variously to his supposed reference to the Civil War as “the great calamity” or to his long series of earlier failures in seeking public office. The moniker, widely repeated by partisan editors, helped portray him as a pessimist or Luddite in an era of economic expansion, and as a doomsayer amid general prosperity. Yet his policy positions often aligned with mainstream Democratic revenue reformers. As a farmer who paid high prices for manufactured goods and received low world-market prices for his crops, he had particular reason to oppose protective tariffs. He introduced a bill to remove the duty on barbed wire, a vital input for farmers, and supported measures aimed at easing the burdens on agricultural producers.

Contrary to his public image as an enemy of all banks and corporations, Weller did not oppose banking institutions per se, nor even the national banking system in its entirety. His principal objection was to the power of national banks to issue their own currency, a stance shared by many Democrats and supported by prominent economists such as William Graham Sumner of Yale University. He also favored legislation that would allow the trade dollar to be redeemed at the Treasury as bullion and recoined into the standard silver dollar—“the dollar of the daddies”—although critics noted that trade dollars could already be melted into bullion and converted into silver dollars under the Bland–Allison Act. Weller’s rhetoric and reform proposals made him a frequent target of Republican newspapers, which depicted him as a blatherskite and attributed to him statements taken out of context or never uttered. When he charged that a cattle inspection bill had been written “in the interest of the cattle ring,” opponents accused him of seeking to reshape the law to serve that very interest. In reality, he had attempted to amend the bill to favor farmers and small shippers, and ultimately voted for it in the hope that the Senate would further improve it.

Weller sought re-election in 1884 with continued, loyal support from Democrats in his district, but he was narrowly defeated by Republican nominee William E. Fuller, losing by a margin of barely two hundred votes. His close loss underscored the strength of his personal following; no mainstream Democratic contender in the district would match his performance over the next six years. After his defeat, he did not return to Congress, and his single term remained his only federal office. Nonetheless, his service in the Forty-eighth Congress marked him as one of the most visible Greenbackers of his time and a prominent advocate for agrarian and monetary reform.

After leaving Congress, Weller remained active in public life and in the evolving agrarian reform movement. He became proprietor and editor of the Farmers’ Advocate, a weekly newspaper published in Independence, Iowa, through which he continued to champion the interests of farmers and rural communities. As the Greenback movement gave way to the broader Populist, or People’s Party, movement, Weller emerged as one of the leading Populists in Iowa. From 1890 to 1914 he served as a delegate to the People’s Party national committee and held the presidency of the Chosen Farmers of America, further cementing his role as a spokesman for agrarian reform.

Within the Populist Party, Weller aligned with the “middle of the road” faction that opposed fusion or close cooperation with the Democratic Party. He strongly resisted any coalition with Democrats and was an outspoken critic of the party’s endorsement of William Jennings Bryan for president in 1896. In a state where Populism never achieved broad electoral success, he led an increasingly forlorn effort to maintain a distinct Populist identity. He was twice an unsuccessful candidate for justice of the Iowa Supreme Court and ran unsuccessfully as the People’s Party candidate for governor of Iowa in 1901. Despite these defeats, he remained a persistent and recognizable figure in third-party politics, advocating for the causes that had defined his public life.

Luman Hamlin Weller died on March 2, 1914, in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He was buried in Greenwood Cemetery near Nashua, in Chickasaw County, Iowa. His career, spanning local legal practice, a single but eventful term in Congress, and decades of leadership in Greenback and Populist circles, reflected the broader struggles of agrarian reformers and third-party movements in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.