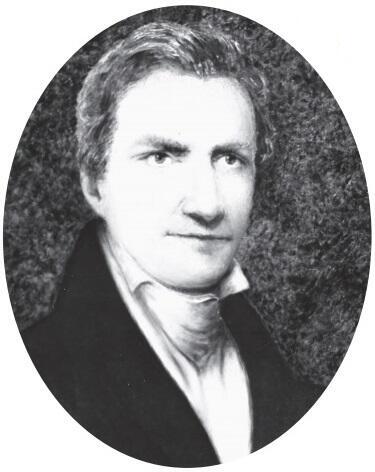

Representative Matthew Lyon

Here you will find contact information for Representative Matthew Lyon, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | Matthew Lyon |

| Position | Representative |

| State | Kentucky |

| District | 1 |

| Party | Republican |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | May 15, 1797 |

| Term End | March 3, 1811 |

| Terms Served | 6 |

| Born | July 14, 1749 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | L000545 |

About Representative Matthew Lyon

Matthew Lyon (July 14, 1749 – August 1, 1822) was an Irish-born American printer, farmer, soldier, and politician who served as a United States Representative from both Vermont and Kentucky. A combative and highly partisan Democratic-Republican, he represented Vermont in the Fifth and Sixth Congresses from 1797 to 1801, and Kentucky in the Eighth through Eleventh Congresses from 1803 to 1811. His tumultuous congressional career included a notorious physical altercation with a fellow representative and his imprisonment under the Alien and Sedition Acts, during which he was re-elected to Congress from his jail cell. His trial, conviction, and incarceration made him a celebrated free-speech martyr among the fledgling Democratic-Republican Party.

Lyon was born in County Wicklow, Ireland, on July 14, 1749, and attended school in nearby Dublin. Some accounts indicate that his father was executed for treason against the British government in Ireland, leaving Lyon to work from a young age to help support his widowed mother. In 1763 he began to learn the trades of printer and bookbinder, but the following year he emigrated to the American colonies as a redemptioner, arriving in Connecticut in 1764. To pay off the cost of his passage, he worked for Jabez Bacon, a farmer and merchant in Woodbury. His indenture was later purchased by Hugh Hannah (or Hanna), a merchant and farmer in Litchfield. While working for Hannah, Lyon continued his education through self-study whenever he could, and by working for wages when permitted he eventually saved enough to purchase the remainder of his indenture. He became a free man in 1768.

While living in Connecticut, Lyon became acquainted with several individuals who would later be among the first white settlers of what became Vermont. In 1774 he moved to Wallingford, in the New Hampshire Grants (later Vermont), where he farmed and organized a company of militia. During the early stages of the American Revolutionary War he served under General Horatio Gates in upstate New York and Vermont. Political opponents later circulated a story that he had been cashiered for cowardice and forced to carry a wooden sword as a mark of shame. Lyon’s own account held that he and his men had been assigned to guard wheat fields near Jericho, Vermont; dissatisfied at being kept from active service, he requested to leave Gates’s command and join the regiment of Seth Warner. His conduct was later vindicated by officers including Arthur St. Clair and James Wilkinson. In 1775 he served as adjutant in Colonel Seth Warner’s regiment in Canada, and in July 1776 he was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Green Mountain Boys. He moved to Arlington, Vermont, in 1777. Lyon subsequently joined Warner’s regiment as paymaster with the rank of captain and saw action at the Battle of Bennington and other engagements. After leaving Warner’s regiment following the Battle of Saratoga, he continued to play an active role in Vermont’s revolutionary government, serving as a member of the Vermont Council of Safety, as a captain and later colonel in the militia, as paymaster general of the Vermont Militia, as deputy secretary to Governor Thomas Chittenden, and as an assistant to Vermont’s treasurer.

Lyon’s civil and political career in Vermont developed alongside his military and administrative service. He represented Arlington in the Vermont House of Representatives from 1779 to 1783. In 1783 he founded the town of Fair Haven, Vermont, and later returned to the state House as Fair Haven’s member from 1787 to 1796. He also served as clerk of the Vermont Court of Confiscation, which handled property seized from Loyalists. In October 1785 he was impeached by the Vermont Council of Censors for failing to provide the state with the court’s records. After an impeachment trial before the council and the governor, he was reprimanded and ordered to pay the expenses of the prosecution, with an additional fine of 500 pounds to be imposed if he did not deliver the documents. Lyon requested and received a new trial, but the council again found against him; there is no record that he ever paid the fines. Despite this controversy, he remained influential in local affairs. He was elected assistant judge of Rutland County in 1786 and again served in the Vermont House the following year.

In Fair Haven, Lyon became a significant local entrepreneur. He built and operated a gristmill, sawmill, and paper mill, as well as an iron foundry. In 1793 he established a printing office and began publishing a newspaper, the Farmers’ Library, nominally owned by his son James but largely managed and written by Lyon himself. The paper was later renamed the Fair Haven Gazette. In 1794 he sold the Gazette’s press and equipment to Reverend Samuel Williams and Judge Samuel Williams of Rutland, who used them to found the Rutland Herald. Lyon was an unsuccessful candidate for election to the Second and Third Congresses and unsuccessfully contested the election of Israel Smith to the Fourth Congress. He finally secured a seat as a Democratic-Republican in the Fifth and Sixth Congresses, serving from March 4, 1797, to March 3, 1801. He did not seek renomination in 1800.

Lyon’s service in the U.S. House of Representatives from Vermont was marked by intense partisan conflict. He became one of the first two members ever investigated for a supposed violation of House rules when he was accused of “gross indecency” for spitting in the face of Representative Roger Griswold of Connecticut; Griswold in turn was investigated for physically attacking Lyon in retaliation. On January 30, 1798, during debate over whether to expel Senator William Blount of Tennessee, Griswold attempted to engage Lyon in discussion, but Lyon, a Democratic-Republican, deliberately ignored the Federalist Griswold. After Griswold called him a “scoundrel,” then regarded as profane insult, Lyon declared his willingness to fight for the interests of the common man. Griswold mockingly asked whether he would use his “wooden sword,” alluding to the story of Lyon’s alleged disgrace under Gates. Enraged, Lyon spat tobacco juice in Griswold’s face, an incident that earned him the nickname “The Spitting Lyon.” Lyon later apologized to the House, claiming he had not realized it was in session when he confronted Griswold and that he intended no disrespect, and he submitted a written apology. On February 15, 1798, however, Griswold retaliated by attacking Lyon with a wooden cane on the House floor, beating him about the head and shoulders. Lyon retreated to a fireplace and defended himself with the tongs until other members intervened, some pulling Griswold away by his legs. A committee recommended censure of both men, but the House rejected the motion after both Lyon and Griswold pledged to keep the peace.

Lyon also became the first person tried under the Alien and Sedition Acts and the only person elected to Congress while in jail. During the Quasi-War with France, he sharply criticized Federalist President John Adams. When the Rutland Herald refused to publish his writings, Lyon launched his own paper, The Scourge of Aristocracy and Repository of Important Political Truth. On October 1, 1798, he printed an editorial charging that Adams possessed an “unbounded thirst for ridiculous pomp, foolish adulation, and selfish avarice,” and accusing him of corrupting Christianity to further his war aims. Before passage of the Alien and Sedition Acts, Lyon had written a letter to Alden Spooner, publisher of the Vermont Journal, in which he called the president “bullying” and described the Senate’s responses as “stupid.” After the Acts became law, Federalists pressed Spooner to print Lyon’s letter, which he did, thereby providing additional grounds for prosecution. Lyon was also charged for publishing letters by poet Joel Barlow that he had read at political rallies, even though these, too, predated the Acts. Lyon sought to defend himself by challenging the constitutionality of the Sedition Act and invoking the Constitution’s prohibition on ex post facto laws, but the court refused to allow this line of defense. On October 10, 1798, he was convicted of violating the Sedition Act. He was sentenced to four months’ imprisonment in a small 16-by-12-foot jail cell in Vergennes, Vermont, used for felons, counterfeiters, thieves, and runaway slaves, and ordered to pay a $1,000 fine and court costs, a sum equivalent to many thousands of dollars in modern terms. Judge William Paterson lamented that he could not impose a harsher penalty. Supporters, including members of the Green Mountain Boys, organized a resistance movement and even threatened to destroy the jail, but Lyon urged peaceful resistance. While incarcerated, he stood for re-election and won a seat in the Sixth Congress by a wide margin, receiving 4,576 votes to his nearest opponent’s 2,444. Upon his release he addressed a cheering crowd with the declaration, “I am on my way to Philadelphia!” Decades later, after persistent efforts by his heirs, Congress in 1840 authorized repayment of the fine and related expenses, with interest.

Lyon also played a notable role in the contingent presidential election of 1800. Because Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr, the Democratic-Republican candidates for president and vice president, received an equal number of electoral votes, the choice was thrown to the House of Representatives, where each state delegation cast a single vote and a majority of nine states was required for election. Many Federalists preferred Burr to Jefferson. On the first 35 ballots Jefferson carried eight states and Burr six, while two states, including Vermont, produced no result because their delegations were evenly divided. In Vermont, Federalist Lewis Morris supported Burr, while Lyon, the lone Democratic-Republican, voted for Jefferson, leaving the state’s vote deadlocked. On the 36th ballot several Federalists broke the impasse by casting blank ballots or absenting themselves, thereby allowing Jefferson to win. Morris was among those who absented themselves, and with his absence Lyon’s vote carried Vermont for Jefferson. Vermont was one of two states that shifted from “no result” to Jefferson on the final ballot, and Jefferson ultimately carried ten states. Lyon thus played an important part in securing Jefferson’s election to the presidency.

By 1801 Lyon had moved west to Kentucky, settling at Eddyville on the Cumberland River in Livingston County, an area later included in Caldwell County and now part of Lyon County, which was ultimately named in his honor. There he established a paper mill powered by oxen, a distillery, and later engaged in boat building. The 1810 census recorded him as the owner of ten enslaved persons, reflecting his participation in the slaveholding economy of the early Kentucky frontier. He entered Kentucky politics as a member of the Kentucky House of Representatives in 1802. The following year he returned to national office, winning election as a Democratic-Republican to the Eighth Congress and to the three succeeding Congresses, serving from March 4, 1803, to March 3, 1811, as a representative from Kentucky. He sought reelection to the Twelfth Congress in 1810 but was unsuccessful.

During the War of 1812, Lyon’s business and public service intersected when the Department of War employed him to build gunboats. He invested heavily in wood and other supplies at wartime prices, but after the war the federal government failed to honor its contract obligations fully, leaving him bankrupt. Lyon worked diligently over the ensuing years to satisfy his creditors, and by 1818 he had repaid his debts and restored himself to comfortable circumstances, though he never succeeded in obtaining full payment for his wartime claims. Seeking a stable federal salary in his later years, he turned again to public service. In 1820 President James Monroe, a political ally and friend, appointed him United States factor to the Cherokee Nation in the Arkansas Territory, a federal post responsible for managing trade and relations with the tribe.

While residing in the Arkansas Territory, Lyon once more attempted to return to Congress. He ran for the territory’s nonvoting delegate seat in the Seventeenth Congress against incumbent James Woodson Bates. In a close contest, Lyon lost by a vote of 1,081 to 1,020 and then formally contested the result. In communications to the House of Representatives he complained that the territorial governor and other officials had refused to allow him to inspect the ballots and returns or to hold a hearing at which he could call witnesses, making it impossible for him to substantiate his claims. Unable to gather the necessary evidence, he withdrew his contest, and Bates retained the seat. Lyon died in office as United States factor at Spadra Bluff in Crawford County, Arkansas (an area now within Clarksville, Johnson County) on August 1, 1822. He was initially buried in Spadra Bluff Cemetery. In 1833 his remains were reinterred in Eddyville Cemetery in Kentucky, returning him to the community where he had spent many of his later years.