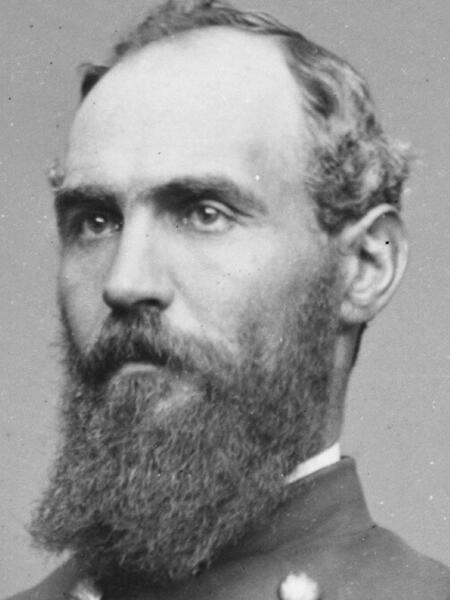

Representative Nelson Taylor

Here you will find contact information for Representative Nelson Taylor, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | Nelson Taylor |

| Position | Representative |

| State | New York |

| District | 5 |

| Party | Democratic |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | December 4, 1865 |

| Term End | March 3, 1867 |

| Terms Served | 1 |

| Born | June 8, 1821 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | T000096 |

About Representative Nelson Taylor

Nelson Taylor (June 8, 1821 – January 16, 1894) was an American lawyer, soldier, and politician who served as a U.S. Representative from New York, a brigadier general in the Union Army during the American Civil War, and a captain in the U.S. Army during the Mexican–American War. He was born in South Norwalk, Connecticut, where he attended the common schools, an early precursor to the modern public education system. Little is recorded about his early family life, but his subsequent military and political career suggests an early exposure to civic affairs and public service in his native Connecticut.

Taylor first came to national attention during the Mexican–American War. On August 1, 1846, he enlisted as a captain in the 1st New York Infantry Regiment. He was sent to California in 1846 just before the outbreak of hostilities and served there through the duration of the conflict. He was honorably mustered out on September 18, 1848. Choosing to remain in California after his discharge, Taylor settled in Stockton and engaged in business, becoming part of the emerging political and commercial life of the new American territory.

In California, Taylor quickly entered public service. He was elected to the first inaugural California Senate from San Joaquin County and served from December 15, 1849, to February 13, 1850, winning his seat with 16.6 percent of the vote in a multi-candidate field. During this brief legislative tenure, he voted for the expansion of the California state government and advocated early for a transcontinental railroad to connect California with the East Coast. On February 13, 1850, he was expelled from the California Senate due to excessive absence while attending to business concerns in New York City, an action taken “without any reflection upon his character.” Upon returning to California, he remained active in public affairs, serving as president of the board of trustees for the State Insane Asylum from 1850 to 1856. He was elected sheriff of San Joaquin County in 1855. In 1856 he resigned his positions, having established extensive political connections in California, and moved back to New York City.

After resettling in New York City in 1856, Taylor pursued formal legal training. He attended Harvard University and graduated from Harvard Law School in 1860. That same year he was admitted to the bar and began practicing law in New York City. Also in 1860 he entered electoral politics in his new home state as the Democratic candidate for the 37th Congress, but he was unsuccessful, losing the election to Republican William Wall. His legal practice and political activity in New York, however, positioned him for a prominent role when civil war broke out the following year.

With the onset of the Civil War, Taylor returned to military service. On July 23, 1861, he was commissioned colonel of the 72nd New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment, part of the Excelsior Brigade. In March 1862 he replaced Daniel Sickles as commander of the division when Sickles was absent; Sickles, a favorite of President Abraham Lincoln and General Joseph Hooker but controversial in Congress, had organized the Excelsior Brigade. As brigade commander, Taylor saw action at the Battle of Williamsburg and the Second Battle of Bull Run. He fought with the Army of the Potomac until September 1862, when, at the recommendation of General George B. McClellan, he was promoted to brigadier general of volunteers. He was then transferred to the I Corps to replace Brigadier General George Hartsuff, who had been wounded at the Battle of Antietam.

Taylor commanded the Third Brigade of the I Corps during the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862, where contemporary accounts noted that he “distinguished himself for his bravery and coolness during action.” At the outset of the battle, he assisted in capturing the bridge at Rappahannock Station, a critical crossing point for Union forces. Because of his reputation for “iron discipline,” he was given command of the front-line troops of General John Gibbon’s division during the initial assault on the Confederate lines. His advance against the brigade of General James Henry Lane, holding the left of Stonewall Jackson’s line, was repulsed, but Taylor rallied his men long enough for supporting forces to arrive. When Gibbon was wounded during the fighting, Taylor assumed command of the division and promptly advanced reserves to reinforce the collapsing center of the Union line. When his troops, short of ammunition, begged him to retreat, he is reported to have replied, “Use the bayonet.” Although his reinforced position held for a time, a strong Confederate line emerged from nearby woods, forcing him to retreat and surrender control of the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad, a vital supply route for both sides. The collapse of the Union center contributed to the failure to take Fredericksburg, and Taylor’s brigade suffered heavy losses, in part due to inferior firepower and an exposed position. Despite the defeat, his conduct drew high praise from both his soldiers and superior officers. Taylor resigned his commission on January 19, 1863, a decision often linked to his disillusionment following the ill-fated “Mud March” under General Ambrose Burnside. He returned to New York City and reopened his law practice.

Taylor reentered national politics near the close of the war. A Democrat identified as a War Democrat because of his support for the Union war effort, he was elected to the 39th Congress and served from March 4, 1865, to March 3, 1867, representing a New York district during a pivotal period in Reconstruction. He defeated Republican William B. McCay with 51 percent of the vote, succeeding former Tammany Hall leader Fernando Wood, a prominent Copperhead Democrat. In the House of Representatives, Taylor served on the Select Committee on Freedmen and participated actively in debates over Reconstruction policy. He was a staunch opponent of continuing and expanding the Freedmen’s Bureau, voting in 1866 against its extension. Taylor argued that the bureau risked “overleap[ing] the mark… and before we are aware of it, not have the freedmen equal before the law, but superior,” and he contended that reports from General Ulysses S. Grant did not call for increased powers for the agency. Although he often voted to protect the civil rights of African Americans, he opposed direct financial assistance to the South in any form and resisted broad federal social programs.

In Reconstruction policy more broadly, Taylor supported President Andrew Johnson’s comparatively lenient plan for reincorporating the former Confederate states into the Union. He voted in favor of allowing elected members from designated districts in Arkansas to take their seats in the House of Representatives, provided they had not participated in the Confederate government. At the same time, he was a strong advocate of expanding federal infrastructure into the West and supported federal aid to Native Americans who had been displaced by westward expansion. Reflecting his long-standing concern for soldiers, he frequently voted to raise the pay of regular army personnel and supported back pay for militia and irregular soldiers who had served in the earlier phases of the Civil War. After one term in office, he was an unsuccessful candidate for reelection in 1866 to the Fortieth Congress, losing to John Morrissey, a famous bare-knuckle boxer whose campaign enjoyed the financial and organizational backing of Tammany Hall, against which Taylor could not effectively compete.

After leaving Congress, Taylor moved back to his birthplace of South Norwalk, Connecticut, in 1869, where he continued to practice law and remained engaged in local affairs. He served several times as city attorney of South Norwalk, contributing his legal expertise to municipal governance. In 1888 he helped to found the Lockwood Manufacturing Hardware Company with Henry S. Lockwood. Taylor served as president of the company, which specialized in builder’s hardware, from its founding until his death in 1894, adding industrial leadership to his record of public and military service. He was also the father of Nelson Taylor Jr., who became mayor of South Norwalk in 1885 and later served as a member of the Connecticut State Senate until 1888, extending the family’s involvement in public life into a second generation.

Nelson Taylor died in South Norwalk, Connecticut, on January 16, 1894. He was interred in Riverside Cemetery. His career, spanning frontier California politics, two major American wars, and the contentious Reconstruction era in Congress, reflected the turbulent national transformations of the mid-nineteenth century and left a record of service in both military and civil spheres.