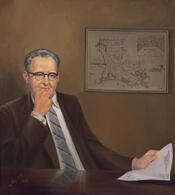

Representative Overton Brooks

Here you will find contact information for Representative Overton Brooks, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | Overton Brooks |

| Position | Representative |

| State | Louisiana |

| District | 4 |

| Party | Democratic |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | January 5, 1937 |

| Term End | January 3, 1963 |

| Terms Served | 13 |

| Born | December 21, 1897 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | B000884 |

About Representative Overton Brooks

Thomas Overton Brooks (December 21, 1897 – September 16, 1961) was a Democratic U.S. Representative from Louisiana who served thirteen consecutive terms in the United States House of Representatives from January 3, 1937, until his death in 1961. Representing the Shreveport-based Fourth Congressional District in northwestern Louisiana, he held office during a quarter century marked by the Great Depression, World War II, the early Cold War, and the dawn of the space age. At the time of his death, he was chairman of the House Committee on Science and Astronautics, having become the first chairman of the newly formed House Space Committee, later known as the House Science and Astronautics Committee.

Brooks was born in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, to Claude M. Brooks and the former Penelope Overton. He came from a prominent political family: he was a nephew of U.S. Senator John Holmes Overton and a great-grandson of Walter Hampden Overton, both influential figures in Louisiana’s political history. He attended and graduated from the public schools and, as a young man, served overseas during World War I as an enlisted man in the Sixth Field Artillery, First Division, Regular Army, from 1918 to 1919. Following his military service, he returned to Louisiana and pursued legal studies, obtaining a law degree in 1923 from what is now the Louisiana State University Law Center in Baton Rouge. He was admitted to the bar the same year and began the practice of law in Shreveport, in Caddo Parish, in the northwestern corner of the state.

On June 1, 1932, Brooks married Mary Fontaine “Mollie” Meriwether, daughter of Minor Meriwether, a planter and banker originally from Hernando, Mississippi, and the former Anne Finley McNutt, both of whom later died in Shreveport. Overton and Mollie Brooks had one child, Laura Anne Brooks (1936–1994), who, like her mother, died in Houston, Texas. As he established his legal and family life in Shreveport, Brooks also became active in civic and veterans’ organizations. Over the years he was a member of the Masonic Lodge, the Shriners, the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks, the American Legion, the Veterans of Foreign Wars, and Kiwanis International. He was an Episcopalian.

Brooks entered electoral politics in the mid-1930s. In his initial campaign for Congress, he faced a hard-fought Democratic primary in the one-party political environment that then dominated Louisiana. He confronted Henry Andrew O’Neal, a Shreveport insurance agent originally from Linden in Cass County, Texas, in a contest that also initially included state Representative Wellborn Jack of Caddo Parish and J. Frank Colbert, the former mayor of Minden. Jack and Colbert were eliminated in the first round of the primary. In the second round of balloting, Brooks prevailed with 19,375 votes (55.6 percent) to O’Neal’s 15,450 (44.4 percent), securing the Democratic nomination and effectively the seat. He took office on January 3, 1937, as a member of the Democratic Party and went on to contribute to the legislative process during thirteen terms in Congress, representing the interests of his northwestern Louisiana constituents.

During his long congressional career, Brooks was repeatedly returned to office and was reelected twelve times. In 1947–1948, he served on the Herter Committee, a special House committee that studied U.S. foreign aid and helped lay groundwork for postwar foreign policy and the Marshall Plan. In the 1948 Democratic primary, he defeated two intra-party challengers: Harvey Locke Carey of Minden, a former short-term U.S. attorney for the United States District Court for the Western District of Louisiana, and former State Senator Lloyd Hendrick, a Natchitoches Parish native residing in Shreveport. Throughout his tenure, Brooks advocated strengthening national defense, expanding the production of natural gas, promoting rural electrification, and securing what he termed “fair prices” for farm, dairy, and ranch products. At the same time, he reflected the segregationist views dominant among many white southern politicians of his era. In 1956, he signed the Southern Manifesto, a congressional statement opposing the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education and attempting, unsuccessfully, to block the desegregation of public schools.

Brooks’s committee assignments and leadership roles grew with his seniority. From 1947 to 1958, he served on the House Committee on Armed Services, where he participated in oversight of military policy during the early Cold War. Despite his length of service, he reportedly was not advanced to the most powerful positions on Armed Services because some colleagues doubted his capacity to handle the highest-responsibility posts. Instead, when the House created a separate committee to oversee the nation’s emerging space and science policy, he was chosen as the first chairman of the newly formed House Space Committee, later the Committee on Science and Astronautics. He was reappointed to this chairmanship in 1961. Brooks played a notable role in shaping the structure of the American space program, advocating that it be organized as a civilian rather than a military enterprise. On May 4, 1961, his committee sent a memorandum to Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson urging a civilian-led space program. A few weeks later, President John F. Kennedy delivered his historic address committing the United States to landing a man on the Moon, a decision that underpinned the Apollo program. Among those who worked on Brooks’s staff were two conservative legislative assistants, Ned Touchstone and Billy McCormack, who later pursued careers in advocacy journalism and the Christian ministry, respectively.

Brooks’s political environment in Louisiana evolved during the 1950s and 1960s as the Republican Party began to challenge Democratic dominance. In his final reelection campaign in 1960, he faced Republican Fred Charles McClanahan Jr. (1918–2007), a Shreveport contractor who had been reared in Homer in Claiborne Parish. McClanahan, a decorated World War II veteran who flew sixty-eight combat missions and received the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Air Medal, and the Purple Heart, ran on a platform calling for the development of a genuine two-party system in Louisiana. He argued that such competition would bring “new recognition and respect in national affairs and stabilize state government with a constant watchdog,” and he endorsed the Nixon–Lodge presidential ticket. McClanahan urged the United States to lead the free world in resisting the spread of communism and in winning the Cold War, insisting that foreign aid be reevaluated in light of national aims. Like Brooks, however, McClanahan affirmed his support for states’ rights and segregation, declaring there was “no right of the United States government to force integration in public schools.” Despite the growing Republican presence and the fact that the Kennedy–Johnson ticket did not carry the Fourth Congressional District, Brooks defeated McClanahan by a wide margin, 74 to 26 percent. During this period, Brooks also drew criticism from some opponents who accused him of tacitly supporting what they termed a “Marxist” foreign policy, and he himself publicly decried inflated home prices and high federal withholding rates from paychecks that, he argued, left many families able to “barely buy groceries.”

The racial tensions of the era occasionally reached Brooks personally. In 1960, during a Ku Klux Klan rally led by Roy Davis, a cross was burned in the front yard of Brooks’s home in Shreveport. The incident prompted a police investigation and the arrest of Davis, underscoring the volatile climate surrounding civil rights and segregation in Louisiana and the broader South. Despite such tensions, Brooks continued to focus much of his legislative attention on defense, energy, and space policy, as well as on economic issues affecting his largely rural and small-city constituency. Overton Brooks’s service in Congress thus coincided with, and was shaped by, a significant period in American history, including the New Deal legacy, World War II, the onset of the Cold War, and the early competition of the space race.

A few months after the roll call vote on enlargement of the House Rules Committee, Brooks suffered a fatal heart attack and died in office at Bethesda Naval Hospital in Bethesda, Maryland, on September 16, 1961. His death placed him among the members of the United States Congress who died in office between 1950 and 1999. Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn, with whom Brooks had served in the Democratic leadership era of the mid-twentieth century, died exactly two months after Brooks. Following his death, Brooks was interred at Forest Park Cemetery East in Shreveport, a burial place for many of the city’s political figures. In recognition of his long service, particularly to veterans and his district, the Veterans Administration Hospital in Shreveport was renamed in his honor in 1988 as the Overton Brooks Veterans Administration Medical Center, located at 510 East Stoner Street south of Interstate 20 and visible from the Clyde Fant Parkway.