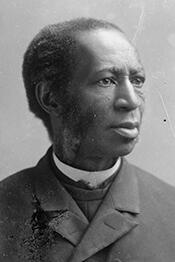

Representative Richard Harvey Cain

Here you will find contact information for Representative Richard Harvey Cain, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | Richard Harvey Cain |

| Position | Representative |

| State | South Carolina |

| District | 2 |

| Party | Republican |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | December 1, 1873 |

| Term End | March 3, 1879 |

| Terms Served | 2 |

| Born | April 12, 1825 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | C000022 |

About Representative Richard Harvey Cain

Richard Harvey Cain (April 12, 1825 – January 18, 1887) was an American minister, bishop, abolitionist, and politician who served as a Republican Representative from South Carolina in the United States Congress from 1873 to 1875 and from 1877 to 1879. His congressional service, encompassing two nonconsecutive terms between 1873 and 1879, occurred during the Reconstruction era, a significant period in American history when newly emancipated African Americans sought political representation and civil rights. In addition to his legislative work, Cain was a prominent leader in the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church and one of the founders of Lincolnville, South Carolina.

Cain was born to a Black father and a Cherokee mother in Greenbrier County, Virginia, an area that is now part of West Virginia. He was raised in Gallipolis, Ohio, a free state where he was permitted to learn to read and write at a time when educational opportunities for people of color were severely restricted in much of the country. As a young man he worked as a barber in Galena, Illinois, and on steamboats along the Ohio River, occupations that exposed him to a wide range of people and ideas in the antebellum Midwest. Licensed to preach in the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1844, he received his first assignment in Hannibal, Missouri, marking the beginning of a long career in the ministry.

Cain pursued higher education at Wilberforce University, one of the first historically Black institutions of higher learning in the United States, and attended divinity school in Hannibal, Missouri. When the American Civil War broke out while he was at Wilberforce, he and 115 fellow students from the largely Black university attempted to enlist in the Union Army but were refused, reflecting the early reluctance of federal authorities to accept Black volunteers. In 1848, frustrated by the segregationist policies of the Methodist Episcopal Church, Cain left that denomination and joined the African Methodist Episcopal Church, an independent Black denomination founded in Philadelphia. By 1859 he had become a deacon in Muscatine, Iowa. In 1861 he was called as pastor of the Bridge Street AME Church in Brooklyn, New York; he was ordained an elder in 1862 and remained at that congregation until 1865.

After the Civil War, Cain moved to Charleston, South Carolina, in 1865 as superintendent of AME missions in the state and presided over Emmanuel Church in Charleston. Under his leadership and that of his colleagues, the AME Church in South Carolina attracted tens of thousands of new members in a short period, becoming a major religious and social institution for newly freed African Americans. His work as a missionary in South Carolina was undertaken at the direction of Bishop Daniel Payne, who appointed him to organize and expand the denomination’s presence in the postwar South. Cain’s religious leadership in Charleston provided a platform for his growing involvement in politics and public life.

Cain became active in Reconstruction-era politics, serving as a delegate to the South Carolina constitutional convention of 1868, which helped reshape the state’s government after the Civil War. That same year he was elected to the South Carolina Senate, representing Charleston County from 1868 to 1872. During this period he also edited the South Carolina Leader newspaper, later renamed the Missionary Record, giving him a voice in public debate and political discourse. As editor, he hired future congressmen Robert B. Elliott and Alonzo Ransier, thereby helping to cultivate a new generation of African American political leadership in the state.

In 1872 Cain was elected as a Republican to the Forty-third United States Congress from a newly created at-large district in South Carolina. He took his seat in March 1873 and served until March 1875. During this first term he was assigned to the Committee on Agriculture, but he devoted much of his energy to civil-rights legislation. He delivered noted speeches in January 1873 in support of what became the Civil Rights Act of 1875, advocating equal access to public accommodations and full citizenship rights for African Americans, although the final law was passed in a diluted form. After redistricting, he chose not to run for re-election in 1874. He returned to electoral politics in 1876, successfully running for the Second Congressional District and serving in the Forty-fifth Congress from March 4, 1877, to March 3, 1879. Throughout his two terms, Cain participated in the legislative process and represented the interests of his South Carolina constituents during a critical phase of Reconstruction and its aftermath.

While serving in Congress, Cain also engaged with broader Black emigration and economic initiatives. In 1877, while advocating for mail service between the United States and West African colonies, he became a member of the Liberian Exodus Joint Stock Steamship Company, which promoted African American migration and commercial links to Liberia and West Africa. Beyond politics, he played a role in community-building in South Carolina as one of the founders of Lincolnville, a town established by African Americans seeking autonomy and landownership in the postwar era.

Cain’s later career was dominated by his leadership in the AME Church. In 1880 he was elected and consecrated a bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal Church and was assigned to an episcopal district that included Louisiana and Texas. In this capacity he helped found Paul Quinn College, an institution of higher learning for African Americans, and served as its president until 1884, furthering educational opportunities for Black students in the South. After his service in the Southwest, he moved to Washington, D.C., where he served as AME bishop over the Mid-Atlantic and New England states, continuing to exercise influence in both religious and civic affairs.

Richard Harvey Cain died in Washington, D.C., on January 18, 1887. He was buried in Graceland Cemetery in the capital, and his remains may have been reinterred at Woodlawn Cemetery about a decade later, when Graceland was closed and many interments were moved. His life and career placed him among the notable African American and Native American members of the United States Congress during Reconstruction, and he is remembered as a clergyman, educator, and legislator who worked to expand civil and political rights in the decades following the Civil War.