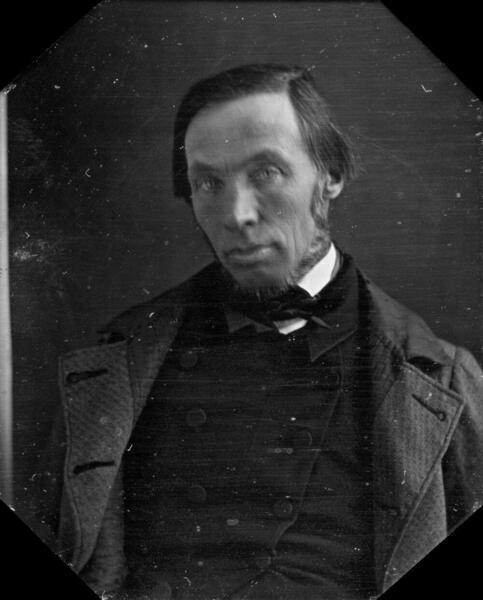

Representative Robert Dale Owen

Here you will find contact information for Representative Robert Dale Owen, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | Robert Dale Owen |

| Position | Representative |

| State | Indiana |

| District | 1 |

| Party | Democratic |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | December 4, 1843 |

| Term End | March 3, 1847 |

| Terms Served | 2 |

| Born | November 7, 1801 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | O000152 |

About Representative Robert Dale Owen

Robert Dale Owen (7 November 1801 – 24 June 1877) was a Scottish-born Welsh-American social reformer, writer, and politician who became a leading figure in Indiana and national public life in the mid-nineteenth century. He was born in Glasgow, Scotland, the eldest son of the noted Welsh-born industrialist and social reformer Robert Owen and his wife, Ann (or Anne) Caroline Dale, the daughter of Scottish textile manufacturer David Dale. Raised in an environment that emphasized rationalism, social improvement, and educational reform, Owen spent part of his youth at New Lanark, Scotland, where his father operated a model industrial community. In 1824–25 he accompanied his father to the United States as part of the elder Owen’s effort to establish a utopian community on the American frontier.

Owen’s early education was informal but rigorous, shaped by tutors and by his father’s progressive educational theories. He was sent for a time to schools in Switzerland and Germany, where he studied modern languages and absorbed continental ideas about social reform and secular education. Returning to Britain, he became increasingly involved in his father’s campaigns for cooperative communities and labor reform. In 1825 he emigrated permanently to the United States, joining his father in Indiana to help found and administer the experimental community of New Harmony on the Wabash River. Although the communal experiment soon failed as a practical enterprise, the experience deeply influenced Owen’s political and social philosophy and provided a base for his later work in education, women’s rights, and abolition.

In the mid-1820s Owen assumed responsibility for the day-to-day operation of New Harmony, Indiana, the socialistic utopian community he helped establish with his father in 1825. He became a knowledgeable exponent of the socialist doctrines of his father and used the community as a platform for educational and social experiments. During this period he joined forces with the Scottish-born reformer Frances Wright. Together they co-edited the New-Harmony Gazette in Indiana in the late 1820s, promoting freethought, secular education, and social equality. After the collapse of the communal experiment, Owen moved to New York City, where in the 1830s he and Wright co-edited the Free Enquirer, a radical newspaper that advocated for workers’ rights, women’s rights, and religious skepticism. He also began publishing a steady stream of pamphlets and tracts, including An Outline of the System of Education at New Lanark (1824), Popular Tracts (1830), and Moral Physiology; or, A Brief and Plain Treatise on the Population Question (1830), which addressed birth control and population issues. In 1833 he engaged in a widely noted public debate on religion, resulting in the volume Discussion on the Existence of God, and The Authenticity of the Bible, co-written with Origen Bacheler.

Owen settled in Indiana and entered public life as a Democrat. He served in the Indiana House of Representatives from 1835 to 1839, where he quickly gained a reputation as a reform-minded legislator. In 1843 he was elected as a Democrat to the U.S. House of Representatives, representing Indiana from 1843 to 1847. During his two terms in Congress he played a decisive role in the creation of the Smithsonian Institution. Owen successfully pushed through the bill that established the Institution, helping to shape its mission as a national center for scientific research and education, and he served on the Smithsonian’s first Board of Regents. He also continued to write and lecture, publishing Labor: Its History and its Prospects, an address delivered at Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1841 and republished in 1851, and Hints on Public Architecture (1849), which reflected his interest in the design of public buildings and monuments.

After leaving Congress, Owen returned to Indiana politics and to constitutional reform. He served again in the Indiana House of Representatives from 1851 to 1853 and was a delegate to the Indiana Constitutional Convention of 1850. At the convention he emerged as a leading advocate of public education and women’s legal rights. Owen secured inclusion of an article in the Indiana Constitution of 1851 that provided tax-supported funding for a uniform system of free public schools and established the office of the Indiana Superintendent of Public Instruction. He was also an early and vocal advocate of married women’s property and divorce rights, pressing for legal recognition of women’s separate property and greater freedom in dissolving abusive or untenable marriages. In 1853 President Franklin Pierce appointed him U.S. chargé d’affaires to the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies at Naples, a diplomatic post he held from 1853 to 1858, during which he represented American commercial and political interests in southern Italy.

Owen’s reform activities broadened further in the years leading up to and during the American Civil War. A committed opponent of slavery, he wrote a series of open letters in 1862 to U.S. government officials, including President Abraham Lincoln and Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase, urging them to adopt a policy of general emancipation. His letter of 23 July 1862 was published in the New York Evening Post on 8 August 1862, and his letter of 12 September 1862 appeared in the same newspaper on 22 September 1862. In another open letter to President Lincoln dated 17 September 1862, Owen argued that slavery should be abolished on moral grounds and contended that emancipation would weaken the Confederacy and strengthen the Union war effort. On 23 September 1862, Lincoln issued a preliminary version of the Emancipation Proclamation, which he had first resolved to do in mid-July. During the Civil War, Owen served on the Ordnance Commission, which was charged with helping to supply the Union Army, and on 16 March 1863 he was appointed to the Freedman’s Inquiry Commission, a body that investigated the condition of formerly enslaved people and that served as a predecessor to the Freedmen’s Bureau. In Emancipation is Peace (1863) and in his report The Wrong of Slavery, the Right of Emancipation, and the Future of the African Race in the United States (1864), he confirmed his view that general emancipation was essential to ending the war and argued that the federal government should provide assistance to freedmen.

In the postwar years Owen continued to press for expanded civil and political rights. Toward the end of his political career he worked to obtain federal voting rights for women. In 1865 he submitted an initial draft for a proposed Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution that would not restrict voting rights to males, seeking to enshrine universal suffrage in the Reconstruction amendments. However, Article XIV, Section 2, in the final version of the Amendment, which became part of the Constitution in 1868, was modified to limit suffrage to male citizens over the age of twenty-one. Despite this setback, Owen remained a prominent voice in national debates over equality, citizenship, and the future of the postwar republic.

Alongside his political and reform work, Owen was a prolific author whose writings ranged from social theory and architecture to religion and spiritualism. A religious skeptic in his youth, he later, like his father, converted to Spiritualism. He became one of its most articulate defenders in the English-speaking world. He published Footfalls on the Boundary of Another World (1859), a widely read collection of purportedly evidential spiritualist narratives, and later The Debatable Land Between this World and the Next (1871–72), in which he elaborated his belief in communication with the dead. His interest in religious history and criticism is reflected in his remark that for a century and a half after Jesus’ death “we have no means whatever of substantiating even the existence of the Gospels, as now bound up in the New Testament,” a “perfect blank of 140 years” that he regarded as a serious historical problem. He also continued to publish on contemporary issues, including The Policy of Emancipation: In Three Letters (1863), Emancipation is Peace (1863), and Beyond the Breakers. A Story of the Present Day. Village Life in the West (1870), a novel first serialized in Lippincott’s Magazine in 1869. Late in life he produced his autobiography, Threading My Way: Twenty-Seven Years of Autobiography (1874), and essays such as “Touching Visitants from a Higher Life,” published in The Atlantic Monthly in January 1875.

In his later years Owen divided his time between Indiana and the East Coast, maintaining his interest in public affairs, literature, and spiritualism. He continued to write articles and correspond with reformers, politicians, and intellectuals, and his papers and correspondence—now preserved in collections such as the Robert Dale Owen collection at the Indiana State Library and the Owen family collection at Indiana University—document his wide-ranging influence on nineteenth-century debates over education, women’s rights, religion, and race. Robert Dale Owen died on 24 June 1877 in Lake George, New York. His career as a legislator, diplomat, writer, and reformer left a lasting imprint on Indiana’s constitutional and educational framework, on the establishment of the Smithsonian Institution, and on national discussions of emancipation, civil rights, and spiritual belief in the United States.