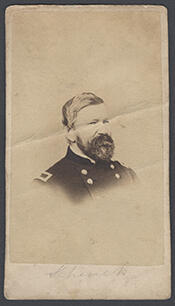

Representative Robert Cumming Schenck

Here you will find contact information for Representative Robert Cumming Schenck, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | Robert Cumming Schenck |

| Position | Representative |

| State | Ohio |

| District | 3 |

| Party | Republican |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | December 4, 1843 |

| Term End | March 3, 1871 |

| Terms Served | 8 |

| Born | October 4, 1809 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | S000118 |

About Representative Robert Cumming Schenck

Robert Cumming Schenck (October 4, 1809 – March 23, 1890) was an American lawyer, legislator, Union Army general in the American Civil War, and diplomat who served as United States Minister to Brazil and to the United Kingdom. He represented Ohio in the United States House of Representatives in two separate multi-term periods between 1843 and 1871, and from 1871 to 1876 served as U.S. Minister to Britain under President Ulysses S. Grant. Over the course of eight terms in Congress, he was an influential Whig and later Republican lawmaker who participated actively in the legislative process during a transformative era in American political and military history.

Schenck was born on October 4, 1809, in Franklin, Warren County, Ohio, to William Cortenus Schenck (1773–1821) and Elizabeth Rogers (1776–1853). His father, descended from a prominent Dutch family and born in Monmouth County, New Jersey, was a land speculator and one of the important early settlers of Ohio. William C. Schenck had served in the War of 1812 and, like his son later, rose to the rank of general. He died when Robert was twelve years old, after which the boy was placed under the guardianship of General James Findlay, a leading figure in early Ohio and Cincinnati civic life. Schenck’s eldest brother, James Findlay Schenck, later had a distinguished naval career and became a rear admiral in the United States Navy, underscoring the family’s long association with public service.

In 1824, at the age of fifteen, Schenck entered Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, as a sophomore and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree with honors in 1827. He remained in Oxford after graduation, devoting himself to extensive reading and serving as a tutor in French and Latin until 1830, when he received the degree of Master of Arts. He then began the study of law under the guidance of Thomas Corwin, a prominent Ohio lawyer and future governor and U.S. senator. Admitted to the bar in 1831, Schenck moved to Dayton, Ohio, where he quickly rose to a commanding position in his profession. For many years he practiced in partnership with Joseph Halsey Crane in the firm of Crane and Schenck, building a substantial reputation as an able advocate. On August 21, 1834, he married Renelsche W. Smith (1811–1849) at Nissequogue, Long Island, New York. The couple had six daughters, three of whom died in infancy; three daughters survived him. His wife died of tuberculosis in 1849 in Dayton.

Schenck’s first significant involvement in politics came in 1838, when he ran unsuccessfully for the Ohio state legislature; he succeeded in winning a term in 1841. During the presidential campaign of 1840 he gained recognition as one of the ablest Whig orators in support of William Henry Harrison. In 1843 he was elected to the United States House of Representatives from an Ohio district and was re-elected in 1845, 1847, and 1849. During this first congressional service he served as chairman of the Committee on Roads and Canals in the Thirtieth Congress and became known for his opposition to the Mexican–American War, which he denounced as a war of aggression intended to extend slavery. One of his early conspicuous achievements in the House was his role in efforts to repeal the “gag rule” that had long been used to prevent antislavery petitions from being read or considered on the House floor. He declined to run for re-election in 1851.

In March 1851 President Millard Fillmore appointed Schenck as United States Minister to Brazil, and he was also accredited to Uruguay, the Argentine Confederation, and Paraguay. Acting under instructions from Washington, he visited Buenos Aires, Montevideo, and Asunción to negotiate treaties with the republics along the Río de la Plata and its tributaries. Several treaties were concluded that granted the United States commercial advantages not accorded to any European power, although a treaty of commerce with Uruguay failed of ratification in the U.S. Senate after the Democratic victory in 1852. Schenck returned to Ohio in 1854. Although he generally sympathized with the emerging Republican Party, his strong personal antipathy to John C. Frémont led him to take no active part in the 1856 presidential election. He resumed and expanded a lucrative law practice, became president of the Fort Wayne Western Railroad Company, and remained active in public affairs. By the late 1850s he was firmly aligned with the Republican Party. In September 1859 he delivered a notable speech in Dayton on the rising sectional animosity in the country, in which he recommended that the Republican Party nominate Abraham Lincoln for the presidency—an endorsement that has been cited as among the earliest public calls for Lincoln’s nomination. Schenck supported Lincoln vigorously at the Chicago Convention in 1860 and throughout the ensuing campaign.

When the Civil War began with the attack on Fort Sumter in April 1861, Schenck promptly tendered his services to President Lincoln. He later recalled that Lincoln asked, “Schenck what can you do to help me?” and, upon hearing his willingness to do anything required, responded, “Well, I want to make a general out of you.” Schenck, who had studied military science but had no prior active military service, was commissioned a brigadier general of volunteers. On June 17, 1861, he commanded the 1st Ohio Volunteer Infantry Regiment (a 90‑day unit) in operations along the Alexandria, Loudon and Hampshire Railroad in Fairfax County, Virginia, an expedition that culminated in the minor Union defeat at the Battle of Vienna, Virginia. His force, riding in open rail cars, was ambushed by Confederate troops under Colonel Maxcy Gregg; the Union suffered several casualties and lost equipment and cars, and Schenck and his officers were criticized for failing to send skirmishers ahead and for disregarding a local Union sympathizer’s warning. Schenck next commanded a brigade in Brigadier General Daniel Tyler’s division at the First Battle of Bull Run on July 21, 1861. Although the Union army was routed, elements of his brigade, together with regulars under Major George Sykes, the brigade of Colonel Louis Blenker, the brigade of Colonel Erasmus Keyes, and the 1st and 2nd Rhode Island Infantry, withdrew from the field in comparatively good order.

Subsequently, Schenck served under Major General William Rosecrans in western Virginia and under Major General John C. Frémont in the Luray Valley. He took part in Stonewall Jackson’s 1862 Valley Campaign, including the Battle of Cross Keys, and for a time commanded the I Corps in Major General Franz Sigel’s absence. Ordered to join Major General John Pope’s Army of Virginia, he arrived just before the Second Battle of Bull Run in August 1862 and was heavily engaged on both days of fighting. He was severely wounded on the second day, suffering a permanent injury to his right arm. He was promoted to major general of volunteers on September 18, 1862, to rank from August 30, 1862. Unfit for field duty for several months, he was assigned to command the VIII Corps, which included the strategically sensitive and politically divided state of Maryland. In this role he was charged with repressing disloyalty and acts of complicity with treason, a policy that made him unpopular among Confederate sympathizers and other disaffected residents. He remained in this command until December 1863, when he resigned his commission to take his seat in Congress.

Schenck’s second period of congressional service began with his election as a Republican from Ohio’s Third Congressional District (Dayton) during the Civil War. He defeated Democrat Clement L. Vallandigham, a prominent Copperhead and critic of the Lincoln administration who was running in absentia after being arrested and deported by federal authorities for a speech delivered in Mount Vernon, Ohio. Schenck served continuously in the House from 1863 to 1871, encompassing the Thirty‑Eighth, Thirty‑Ninth, Fortieth, and Forty‑First Congresses, and in total he served as a Representative from Ohio from 1843 to 1871. During this second stint he quickly assumed a leadership role and was made chairman of the Committee on Military Affairs. In military legislation he was regarded as a firm friend of volunteer soldiers in opposition to what he considered the undue pretensions of the regular army; he was a relentless foe of deserters, a vigorous advocate of the draft, and the author of provisions disfranchising those who evaded conscription. He also became a leading figure in fiscal and economic policy, serving as chairman of the powerful Committee on Ways and Means, where he played a significant role in shaping postwar revenue and monetary legislation. Historian Alexander Del Mar later suggested that Schenck was instrumental in passage of a measure denominating U.S. currency in gold alone, rather than in both gold and silver, a change that has been linked to the financial strains culminating in the Panic of 1873. A member of the Republican Party during this era, he contributed to the legislative process as a prominent House leader during the Civil War and Reconstruction.

After narrowly failing re-election by just fifty-three votes in 1870, Schenck was appointed by President Ulysses S. Grant as United States Minister to the United Kingdom. He sailed for England in July 1871 and soon became involved in the resolution of the Alabama Claims, serving as a member of the commission that settled American demands for damages arising from the depredations of the Confederate commerce raider CSS Alabama and other British-built vessels commanded by Raphael Semmes and others. His social presence in London society also had an unexpected cultural impact. At a royal gathering in Somerset attended by Queen Victoria, Schenck was persuaded by a duchess to write down his rules for the American card game of draw poker. She privately printed these rules for use at court, producing what is regarded as the first booklet devoted solely to draw poker published on either side of the Atlantic. The game rapidly gained popularity in Britain, where it became widely known as “Schenck’s poker.”

Schenck’s diplomatic career in London was marred by the Emma Silver Mine scandal. In October 1871 he allowed his name to be used, for compensation, in the promotion and sale of stock in the Emma Silver Mine, near Alta, Utah, on the London market, and he became a director of the company. The presence of the American minister’s name on the board encouraged heavy British investment. The mine paid substantial dividends for a brief period while insiders sold their holdings, but share prices collapsed when it became evident that the ore body was largely exhausted. British investors blamed Schenck, and the U.S. government, concerned about the appearance of impropriety, ordered him home for investigation. He resigned his diplomatic post in the spring of 1875. A congressional investigation in March 1876 concluded that he was not guilty of criminal wrongdoing, but it censured his judgment in permitting his official position and name to be used in connection with a speculative private enterprise.

Returning to the United States in 1875, Schenck resumed the practice of law in Washington, D.C. He continued to write and lecture and remained an active figure in legal and political circles. In 1880 he privately published a small volume on card play, Draw. Rules for Playing Poker (Brooklyn, 17 pages), further codifying the rules of the game he had helped popularize in Britain. Schenck was widely regarded as an accomplished scholar, well informed on international and constitutional law, deeply versed in political history, and familiar with modern literature in English, French, and Spanish. He died in Washington, D.C., on March 23, 1890, at the age of eighty, and was interred in Woodland Cemetery and Arboretum in Dayton, Ohio. Three of his daughters survived him, and his long public career left a record of service as legislator, soldier, and diplomat during some of the most consequential decades in nineteenth-century American history.