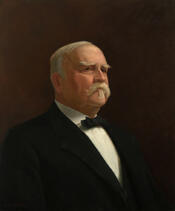

Senator Roger Quarles Mills

Here you will find contact information for Senator Roger Quarles Mills, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | Roger Quarles Mills |

| Position | Senator |

| State | Texas |

| Party | Democratic |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | December 1, 1873 |

| Term End | March 3, 1899 |

| Terms Served | 12 |

| Born | March 30, 1832 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | M000777 |

About Senator Roger Quarles Mills

Roger Quarles Mills (March 30, 1832 – September 2, 1911) was an American lawyer, Confederate Army officer, and Democratic politician who represented Texas in the United States House of Representatives from 1873 to 1892 and in the United States Senate from 1892 to 1899. Over the course of his long congressional career, he became one of his party’s leading authorities on tariff policy and a prominent, if often combative, figure in national Democratic politics. His service in Congress occurred during a significant period in American history, spanning Reconstruction, the rise of industrial America, and the intense national debates over tariffs, silver coinage, and economic policy.

Mills was born in Todd County, Kentucky, on March 30, 1832, and attended the common schools of the area. In 1849 he moved to Texas, which would remain his home for the rest of his life. He pursued the study of law there and, despite his youth, was admitted to the bar at the age of 20 after the Texas legislature made an exception to the usual age requirement. He commenced the practice of law in Corsicana, Texas, where he quickly established himself as a capable attorney. His early legal career in Corsicana laid the foundation for his entry into public life and his later prominence in state and national politics.

Mills’s first elective office was in the Texas House of Representatives, where he served from 1859 to 1860. With the outbreak of the American Civil War, he enlisted in the Confederate States Army. He initially served as a private and took part in the Battle of Wilson’s Creek. Rising through the ranks, he ultimately became a colonel and commanded the 10th Texas Infantry Regiment. Under his command, the regiment saw action at Arkansas Post, Chickamauga—where he led the brigade of General James Deshler during part of the battle—Missionary Ridge, and throughout the Atlanta campaign. His wartime service enhanced his standing among Texas Democrats in the postwar era and helped propel his subsequent political career.

After the Civil War, Mills resumed his law practice in Corsicana and soon entered national politics. A Democrat, he was elected to the United States House of Representatives from Texas and served continuously from 1873 to 1892. During these twelve terms in the House, he represented the interests of his Texas constituents while emerging as one of the ablest, if hottest-tempered, debaters on the Democratic side. Contemporary observers described him as “possessed of the demon of work,” and journalist Frank G. Carpenter portrayed him in 1888 as tall, straight, broad-chested, and physically imposing, a “fighter” who brought a trained mind to legislative warfare and inspired confidence among supporters.

In the 1880s, Mills became particularly prominent as an opponent of high tariffs and as a critic of the growing Prohibition movement in Texas. Amid rising Prohibition sentiment, he refused to make political concessions to temperance advocates. He was reported to have said, “If lightning were to strike all the drunkards, there would not be a live Prohibition party in Texas,” a remark he later insisted had been misquoted to omit his qualifier that “there would not be many [members of the party] left.” He was also quoted as declaring that “a good sluice of pine top whiskey would improve the morals of the Dallas [Prohibition] convention and the average Prohibitionist,” though he denied using the phrase “average Prohibitionist.” These controversies reinforced his reputation as a man of strong views and a sometimes tempestuous style.

Mills made the tariff his special field of study and came to be recognized as one of the leading Democratic authorities on the subject. After the defeat of House Ways and Means Committee Chairman William R. Morrison in the 1886 elections, Mills became chairman of the United States House Committee on Ways and Means when the Fiftieth Congress convened. As the leading Democrat on this influential committee during the first Grover Cleveland and Benjamin Harrison administrations, he advocated trade liberalization and substantial reductions in protective duties. Historian Ida Tarbell later wrote that his selection as chairman was “a red rag to the high protectionists,” as he was regarded as an “out-and-out free trader.”

The high point of Mills’s tariff work came with the so‑called Mills Tariff Bill of 1888. Responding to President Cleveland’s December 6, 1887 annual message, which urged a drastic reduction of tariffs to promote trade and lower the cost of living, Mills had already been drafting a bill since September 1887, using the Walker Tariff of 1846 as a guideline. His proposal sought to reduce duties on sugar, earthenware, glassware, plate glass, woolen goods, and other articles; to substitute ad valorem for specific duties in many cases; and to place items such as certain kinds of lumber, hemp, wool, flax, borax, tin plates, and salt on the free list. Although the measure initially threatened to split the Democratic Party, by the time it passed the House on July 21, 1888, only four Democrats voted against it, and the high-tariff wing of the party in the House had been largely wiped out. Nonetheless, the Republican-controlled Senate heavily amended the bill, and it never became law. Instead, it became the central issue of the 1888 presidential election, with critics warning that American manufacturers could not compete with foreign goods and campaign crowds chanting “No! no! no Free Trade!” Despite the bill’s relatively modest average reduction of about seven percent, it was portrayed as radical, and the tariff controversy helped Republican Benjamin Harrison, a strong protectionist, win the presidency in the Electoral College even while losing the national popular vote. Mills, however, did not succeed in enacting significant tariff reduction legislation and was unable to prevent the subsequent passage of the McKinley Tariff of 1890 after Republicans gained control of the House on a pro-tariff platform.

Mills’s prominence naturally led to ambitions for higher leadership within the House. When Democrats regained control of the chamber in 1891, he sought the speakership following the retirement of John G. Carlisle. In the Democratic caucus he faced Representative Charles F. Crisp of Georgia and, for a time, appeared to be the frontrunner, with as many as 120 votes pledged to him. Mills, however, refused to trade committee assignments or make political deals to secure support. Some two dozen members sought guarantees of specific chairmanships in exchange for their votes, and Representative William Springer of Illinois reportedly offered to withdraw from the race if Mills would promise him the Ways and Means chairmanship. Mills brusquely declined to bargain, and Springer instead withdrew in favor of Crisp, who later made him chairman of Ways and Means. On the thirtieth ballot, Mills received only 105 votes to Crisp’s 119. His refusal to engage in the usual political bargaining, combined with concerns among some Democrats about his volatile temper and his strong association with aggressive tariff reform at a time when many Southern Democrats prioritized free silver, contributed to his defeat. Mills reacted bitterly, issuing a public letter asserting that the party had been harmed more than he by the outcome and warning that a large element that had been voting with the Democrats might abandon them unless those who had opposed him were rebuked.

In 1892, Mills was elected by the Texas legislature to the United States Senate to fill the vacancy created by the resignation of John H. Reagan. He served in the Senate from 1892 until 1899. As a senator, he continued to play a role in the major economic debates of the 1890s. In 1893, when President Cleveland sought repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, Mills gave loyal support to the administration. This stance, however, ran counter to the strong pro-silver sentiment prevalent in Texas and among many Democrats in the South and West. His support for repeal was widely viewed by his constituents as a betrayal of their economic interests and is believed to have contributed significantly to his failure to secure reelection in 1898. Former Representative William L. Wilson of West Virginia, once Mills’s close ally in tariff reform, noted in his diary in 1896 that Mills seemed to have “gone to pieces” since his days as a leading tariff reformer, criticizing what he described as Mills’s “extreme and wild jingo” speech on the Cuban question and his erratic course on financial issues.

After leaving the Senate in 1899, Mills returned to private life in Texas. He resumed his residence in Corsicana, where he had begun his legal career half a century earlier. Though no longer in office, his long record in Congress—twelve terms in the House and one full term in the Senate—left a lasting imprint on Texas politics and on the national Democratic Party’s debates over tariffs and monetary policy. He died in Corsicana on September 2, 1911. In recognition of his service and prominence, Roger Mills County in Oklahoma was named in his honor.