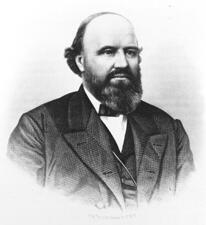

Senator Samuel Clarke Pomeroy

Here you will find contact information for Senator Samuel Clarke Pomeroy, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | Samuel Clarke Pomeroy |

| Position | Senator |

| State | Kansas |

| Party | Republican |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | July 4, 1861 |

| Term End | March 3, 1873 |

| Terms Served | 2 |

| Born | January 3, 1816 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | P000423 |

About Senator Samuel Clarke Pomeroy

Samuel Clarke Pomeroy (January 3, 1816 – August 27, 1891) was a Republican politician who represented Kansas in the United States Senate from 1861 to 1873, serving two terms during the American Civil War and Reconstruction. Over the course of his public life he served in the Massachusetts House of Representatives, was mayor of Atchison, Kansas, and played a leading role in the early development of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad, becoming its second president and the first to oversee its construction and operations. His senatorial career encompassed major national debates over slavery, the conduct of the war, Reconstruction policy, and western development, and later became embroiled in a highly publicized bribery controversy.

Pomeroy was born on January 3, 1816, in Southampton, Hampshire County, Massachusetts. He grew up in New England and pursued higher education at Amherst College in Amherst, Massachusetts. In his early adulthood he became active in state politics and reform causes, and he served in the Massachusetts House of Representatives, gaining legislative experience that would later inform his work in the United States Senate. During these years he developed strong antislavery convictions, aligning himself with the emerging political movements that opposed the expansion of slavery into the western territories.

By the mid-1850s, Pomeroy’s opposition to slavery drew him into the struggle over the future of Kansas Territory. In 1854 he became affiliated with the New England Emigrant Aid Company, an organization formed to encourage and support the migration of antislavery settlers to Kansas following the passage of the Kansas–Nebraska Act. That fall he led a group of settlers westward and helped found the city of Lawrence, Kansas, which became a principal center of Free-State activity. As Kansas developed its civic institutions, Pomeroy continued to rise in prominence. He was elected mayor of Atchison, Kansas, serving from 1858 to 1859, and became involved in early railroad promotion in the region.

Pomeroy’s business interests expanded significantly with the growth of rail transportation. He became associated with the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad, one of the major lines that would eventually link the Midwest to the Southwest. On January 13, 1864, he succeeded Cyrus K. Holliday as the second president of the railroad. In this capacity he was the first president to oversee any of the railroad’s actual construction and operations, guiding the enterprise during its formative years and helping to lay the groundwork for its later expansion across the plains.

With Kansas’s admission to the Union in 1861, Pomeroy moved onto the national stage. On April 4, 1861, the Kansas legislature elected him, along with James H. Lane, as one of the state’s first United States senators. A member of the Republican Party, he took his seat just as the Civil War began and served in the Senate from 1861 to 1873, participating in the legislative process during one of the most consequential periods in American history. In the Senate he represented the interests of his Kansas constituents while supporting the Union war effort and the broader Republican program. In 1862 he backed “Linconia,” a plan to resettle freed African Americans outside the United States, reflecting one strand of contemporary Republican thinking about emancipation and its consequences.

Pomeroy’s senatorial career intersected with leading figures of the era. In 1863, during the Civil War, he escorted abolitionist orator Frederick Douglass to the War Department in Washington, D.C., for a meeting with Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton; afterward, Douglass proceeded to a meeting with President Abraham Lincoln at the White House. Pomeroy also played a controversial role in the presidential politics of 1864. That year he chaired a committee of Republicans who sought to promote Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase as the party’s presidential nominee in place of the incumbent, Lincoln. The group, commonly known as the Pomeroy Committee, issued a confidential circular in February 1864 to influential Republicans criticizing Lincoln’s leadership and urging support for Chase. The circular, once exposed, had the unintended effect of rallying Republicans around Lincoln and severely damaging Chase’s prospects for the nomination.

During his later years in the Senate, Pomeroy turned his attention to western lands and conservation. Influenced by the findings of the Hayden Geological Survey of 1871 and at the urging of geologist Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden, he introduced into the Senate on December 18, 1871, the Act of Dedication bill that ultimately led to the creation of Yellowstone National Park. This legislative initiative contributed to the establishment of the first national park in the United States, marking an early federal commitment to the preservation of natural landscapes.

Pomeroy’s political fortunes declined sharply in 1873 amid allegations of corruption. During the Kansas senatorial election of that year, it was charged that he had paid $7,000 to Alexander M. York, a Kansas state senator, to secure York’s vote for his reelection by the Kansas legislature. York publicly revealed the payment, asserting it was an attempted bribe and part of a scheme to expose Pomeroy. After nineteen ballots, Pomeroy was defeated when legislators turned instead to John J. Ingalls. On February 10, 1873, Pomeroy took to the Senate floor to deny the accusations, characterizing them as a “conspiracy … for the purpose of accomplishing my defeat,” and he called for the creation of a special committee to investigate. The payment itself was not disputed, but witnesses before the Special Committee on the Kansas Senatorial Election testified that the $7,000 was intended as seed money to be passed to a second individual to start a national bank, rather than as a bribe. In its report of March 3, 1873, the committee concluded that there was insufficient evidence to sustain the bribery charge and described the affair as part of a “concerted plot” to defeat Pomeroy. Senator Allen G. Thurman of Ohio dissented from these findings, stating his belief in Pomeroy’s guilt and calling the alternative explanations “so improbable, especially in view of the circumstances attending the senatorial election, that reliance cannot be placed upon them.” Thurman did not press the matter further, as March 3 was Pomeroy’s final day in office. The episode entered popular culture through Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner’s satire “The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today,” in which the character Senator Dillworth is widely understood to be based on Pomeroy.

After leaving the Senate, Pomeroy remained intermittently active in public affairs. On October 11, 1873, he survived an assassination attempt in Washington, D.C., when Martin F. Conway, a former Kansas congressman, fired three shots at him on New York Avenue; one bullet struck Pomeroy in the chest but deflected off his breastbone, and he survived the attack. He later reemerged on the national political scene in the 1880 presidential election as the vice-presidential running mate of John W. Phelps on the ticket of the revived Anti-Masonic Party, a minor party that had largely faded since its prominence in the 1830s. Pomeroy spent his later years away from elective office. He died on August 27, 1891, closing a career that had spanned state and national legislatures, municipal office, railroad leadership, and significant involvement in the central political and moral controversies of the mid-nineteenth century.