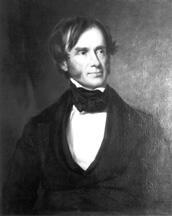

Senator William Segar Archer

Here you will find contact information for Senator William Segar Archer, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | William Segar Archer |

| Position | Senator |

| State | Virginia |

| Party | Whig |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | December 6, 1819 |

| Term End | March 3, 1847 |

| Terms Served | 9 |

| Born | March 5, 1789 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | A000275 |

About Senator William Segar Archer

William Segar Archer (March 5, 1789 – March 28, 1855) was a Virginia politician, planter, and lawyer who served several times in the Virginia House of Delegates, in the United States House of Representatives from 1820 to 1835, and in the United States Senate from 1841 to 1847. A member of the Whig Party in his later national career, Archer represented Virginia in Congress during a significant period in American history and contributed to the legislative process over nine terms in office.

Archer was born at “The Lodge” (also known as “Red Lodge”) in Amelia County, Virginia, to John Archer (1746–1812) and the former Elizabeth Eggleston (d. 1826). He received a private education appropriate to his social and economic standing and graduated from the College of William & Mary in 1806. His family was closely connected to the Revolutionary generation: his uncle Joseph Eggleston (1754–1811), a former Revolutionary War soldier from Middlesex County, moved to Amelia County, where he became a planter, politician, and local justice of the peace, and another uncle, Lt. Richard Tanner Archer, also a Revolutionary War veteran, settled in Amelia County. Archer’s father and a younger brother both died in 1812, around the time Archer was completing his legal training. He read law, possibly under the guidance of his uncle Joseph Eggleston, and prepared for a career that combined legal practice, politics, and plantation management.

Admitted to the bar in 1810, Archer established a private legal practice in Amelia and neighboring Powhatan Counties. At the same time, he developed and operated a plantation in Amelia County that relied on enslaved labor. Census records document the growth of his slaveholding over time: in the 1820 federal census, John R. Archer (possibly his father, although he had died in 1812) was recorded as owning 51 enslaved people, while William S. Archer owned 32. By the 1830 census Archer owned 25 enslaved people, a number that rose to 50 by 1840 and to 68 by the 1850 federal census. By the time of his death, he held 88 enslaved individuals and owned land both in Amelia County and in Mississippi. Archer married and had one daughter, who predeceased him; at his death he was survived by several sisters and by an illegitimate son.

Archer entered public life in the Virginia House of Delegates, where he represented Amelia County as one of its two part-time delegates. Between 1812 and 1819 he was elected to the House of Delegates on four occasions, although he also failed to win reelection once during that period. His speeches and positions led at least one historian to characterize his political stance as conservative and undemocratic, and Amelia County voters declined to elect him as a delegate to either the Virginia constitutional convention of 1829–1830 or that of 1850. Despite these setbacks at the state level, Archer’s legal and political reputation continued to grow, and he became involved in educational affairs as a trustee of Hampden–Sydney College, serving in that capacity from 1820 through 1839.

Archer advanced to national office when he won election to the United States House of Representatives to fill the vacancy caused by the resignation of James Pleasants, who had been chosen by the Virginia General Assembly for the United States Senate. Taking his seat in 1820, Archer quickly aligned himself with a conservative, states’ rights interpretation of the Constitution. He introduced a resolution denying that Congress possessed constitutional authority to charter the Bank of the United States, reflecting his skepticism of centralized financial power. He was reelected to the House in 1820, 1824, 1826, 1828, 1830, and 1832, serving continuously from 1820 to 1835. In several of these contests—1823, 1825, 1827, 1829, 1831, and 1833—he was reelected without opposition, underscoring his strong standing among his constituents. During his House service he rose to prominence as chairman of the Committee on Foreign Affairs from 1829 to 1835. In presidential politics, Archer supported William H. Crawford in 1824 and backed Andrew Jackson in the subsequent election, but he broke with the Jacksonian Democrats after President Jackson ordered the removal of federal deposits from the Bank of the United States. This dispute over executive power and financial policy led Archer to join the emerging Whig Party, though he did not share Whig leader Henry Clay’s enthusiasm for federally funded internal improvements. In 1834 he was defeated for reelection by Democrat John Winston Jones, ending his fifteen-year tenure in the House.

With the rise of Whig influence in the Virginia General Assembly by 1840, Archer returned to national office. On the second ballot, the legislature elected him to the United States Senate over the incumbent, William H. Roane. Archer served a full term in the Senate from 1841 to 1847. During his Senate service he chaired the Committee on Foreign Relations from 1841 to 1845 and the Committee on Naval Affairs from 1841 to 1843. His tenure coincided with intense national debates over territorial expansion and slavery. Archer supported President James K. Polk’s efforts to resolve the Oregon boundary dispute in favor of the United States and to end British claims to the Oregon Territory, but he opposed the annexation of Texas, fearing it would provoke war with Mexico, as it ultimately did. He was also identified as a key member of the committee that drafted the Missouri Compromise, reflecting his involvement in earlier efforts to manage sectional conflict over slavery’s expansion. Although he remained an influential Whig senator, Archer lacked sufficient support in the Virginia General Assembly to secure a second Senate term. In 1846 legislators chose Robert M. T. Hunter over Archer and then-Governor (and future Confederate general) William “Extra Billy” Smith.

After leaving the Senate in 1847, Archer resumed his legal practice and devoted increased attention to the management of his plantations and extensive landholdings in Virginia and Mississippi. He continued to live at “The Lodge” in Amelia County, where he had been born, and remained a figure of local prominence, though he held no further major public office. His later years were spent overseeing his agricultural operations, his enslaved workforce, and his substantial personal library and estate.

William Segar Archer died at “The Lodge” in Amelia County on March 28, 1855. He was interred in the family cemetery on the property. At his death he left a large estate, including approximately 2,000 acres of land, a library of about 2,500 books, numerous enslaved people, and other property. He bequeathed this estate to his three surviving sisters, who chose to divide it into four parts in order to provide for Archer’s illegitimate son, William Segar Archer Work, thus extending the family’s holdings and influence into the next generation.