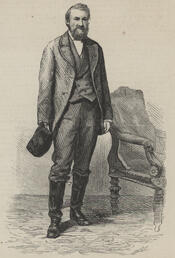

Representative William Crutchfield

Here you will find contact information for Representative William Crutchfield, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | William Crutchfield |

| Position | Representative |

| State | Tennessee |

| District | 3 |

| Party | Republican |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | December 1, 1873 |

| Term End | March 3, 1875 |

| Terms Served | 1 |

| Born | November 16, 1824 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | C000961 |

About Representative William Crutchfield

William Crutchfield (November 16, 1824 – January 24, 1890) was an American politician, businessman, and Southern Unionist who represented Tennessee’s 3rd congressional district in the United States House of Representatives for one term from 1873 to 1875. A member of the Republican Party, he contributed to the legislative process during a significant period in American history, participating in the democratic process and representing the interests of his constituents during the Forty-third Congress. Known for his eccentric personality, plain manner, and staunch loyalty to the Union, he was a prominent civic figure in Chattanooga and an influential, if unconventional, participant in Reconstruction-era politics.

Crutchfield was born in Greeneville, Tennessee, on November 16, 1824, the son of Thomas Crutchfield Sr., a brick contractor, and Sarah (Cleage) Crutchfield. He attended common schools in his youth. In 1840 he moved to McMinn County, Tennessee, where he remained for four years before relocating in 1844 to Jacksonville, Alabama. There he established a large farm specializing in grain production and became known for employing innovative farming techniques. During this period he was elected a captain in the local militia and, inspired by Kentucky statesman Henry Clay, aligned himself with the Whig Party and supported local Whig candidates.

In 1850 Crutchfield moved to Chattanooga, Tennessee, where his father had acquired substantial landholdings and established a successful hotel, the Crutchfield House. After the elder Crutchfield’s death in 1850, William’s brother, Thomas Crutchfield Jr., assumed management of the hotel, while William entered local public life. He was elected an alderman of Chattanooga in December 1851 and was reelected in 1854. In the late 1850s he played a key role in the organization of the city’s fire and police departments, helping to lay the foundations of Chattanooga’s municipal services as the town grew into a regional center.

During the secession crisis that followed Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860, Crutchfield remained firmly committed to the Union. On January 22, 1861, Jefferson Davis, who had just resigned from the United States Senate and would soon become president of the Confederate States, stopped at the Crutchfield House while traveling home to Mississippi. In the hotel dining room that evening, Davis delivered a speech praising secession and urging Tennessee to join the Southern cause. Crutchfield, listening nearby, leaped onto a counter and delivered a scathing reply, denouncing Davis as a “renegade and a traitor” and declaring that Tennessee would not be “hood winked, bamboozled and dragged into your Southern, codfish, aristocratic, tory blooded, South Carolina mobocracy.” Reports of the confrontation suggested that some of Davis’s supporters had drawn pistols and that Davis briefly considered challenging Crutchfield to a duel, but Thomas Crutchfield intervened and escorted Davis from the room, preventing further violence. The episode brought Crutchfield regional notoriety as a vocal Southern Unionist. He attended the first session of the pro-Union East Tennessee Convention in Knoxville in late May 1861 and campaigned actively against secession in the Chattanooga area. Remaining in Chattanooga for most of the Civil War, he was arrested by Confederate authorities amid the crackdown following the East Tennessee bridge burnings in November 1861, but he managed to escape. During the war his family sold the Crutchfield House for $65,000 in Confederate currency and used the proceeds to purchase land and tobacco; Crutchfield later sold the tobacco at a profit to Union soldiers.

Although he never formally enlisted in the Union Army, Crutchfield became an important civilian ally of Union forces. He frequently provided intelligence on Confederate troop movements in and around Chattanooga. During the Union bombardment of Chattanooga in August 1863, he was again pursued by Confederate authorities and escaped by swimming across the Tennessee River to reach Union lines. He then supplied commanders of the Army of the Cumberland with detailed information on Confederate positions and served as an honorary captain and local guide throughout the Chickamauga Campaign. He assisted Union officers William B. Hazen and John B. Turchin at the Battle of Brown’s Ferry in October 1863, and Ulysses S. Grant and George H. Thomas at the Battle of Missionary Ridge in November 1863. After Union forces secured Chattanooga, he continued to aid General James B. Steedman and other post commanders until the end of the war. In his memoirs, General Philip H. Sheridan praised Crutchfield, writing that his “devotion to the Union cause knew no bounds” and describing the information he provided as critical to Union success in the Chickamauga Campaign. In April 1864 Crutchfield served as part of the Hamilton County delegation, alongside Alfred Cate and Daniel C. Trewhitt, to the revived East Tennessee Convention in Knoxville, though that meeting, divided over emancipation, accomplished little. In October 1865 he was elected alderman in Chattanooga’s provisional civil government, charged with restoring order in the postwar city, and he was reelected to a full term in December 1865.

In 1872 Crutchfield announced his candidacy for the United States House of Representatives from Tennessee’s 3rd congressional district as a Republican. At the local Republican convention in September 1872 he secured the nomination on the first ballot, defeating two rivals. His Democratic opponent in the general election was David M. Key, a former Confederate and old acquaintance who had witnessed Crutchfield’s confrontation with Jefferson Davis in 1861 and who had written to Crutchfield in 1865 seeking assurances that former Confederates could safely return to Chattanooga. Although Democrats generally dominated the 3rd district in this era, Republicans benefited from a statewide surge in 1872, and Crutchfield narrowly defeated Key, receiving 10,041 votes to Key’s 8,960. He thus entered the Forty-third Congress as a Representative from Tennessee, serving from March 4, 1873, to March 3, 1875. During his single term in office, he participated in the legislative process at a time of intense national debate over Reconstruction and civil rights, representing the interests of his East Tennessee constituents as a member of the Republican Party.

Crutchfield’s tenure in Congress drew attention as much for his personal style as for his legislative work. A Washington Star correspondent observed in 1873 that, since the days of Davy Crockett, Tennessee’s congressional delegations had typically included at least one “mountaineer character,” and that Crutchfield filled this role in the Forty-third Congress. The correspondent described him as a “sunburnt, wiry little man, with foxy hair and whiskers,” who, despite having “considerable means,” dressed in cheap, frayed homespun clothing and wore heavy, well-greased cowhide brogans that reportedly dismayed Pullman car bootblacks. His speeches were often rendered in eye dialect in the press to convey his thick Southern accent. Substantively, his most notable achievement in Congress was securing $600,000 in federal appropriations for improvements to the Tennessee River, along with smaller appropriations for the Little Tennessee and Hiwassee rivers—projects of considerable economic importance to his district and region. During heated House debates over civil rights legislation in early 1873, however, he introduced a facetious amendment that would have made it a crime for a white woman to refuse a marriage proposal from a Black man on the basis of “race, color, and previous condition of servitude.” Intended as a joke, the proposal angered fellow Republicans who were earnestly advocating for civil rights and provoked outrage among both white and Black residents of the 3rd district. Crutchfield did not seek reelection in 1874 and concluded his congressional service at the end of his term in 1875.

In his later years Crutchfield largely withdrew from national politics and devoted himself to agricultural pursuits. He spent much of his time on a 500-acre orchard south of Chattanooga, where he produced fruit and engaged in other farming activities, continuing the agricultural interests he had first developed in Alabama decades earlier. He remained a well-known figure in the region and maintained friendships with prominent contemporaries, including the humorist and author George Washington Harris. After the Civil War, Crutchfield had assisted Harris in becoming president of the Wills Valley Railroad, and Harris, in the “Dedicatory” to his 1867 book Sut Lovingood: Yarns Spun by a Nat’ral Born Durn’d Fool, playfully proposed dedicating the work to Crutchfield. The eventual dedication praised him as “my friend in storm and sunshine, brave enough to be true, and true enough to be singular; one who says what he thinks, and very often thinks what he says,” a characterization that reflected both his reputation for blunt speech and his steadfast Unionism. William Crutchfield died in Chattanooga on January 24, 1890, at the age of 65, and was interred in the family lot at Citizens Cemetery in Chattanooga, Tennessee.