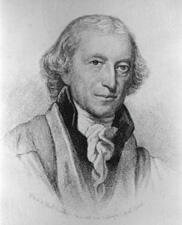

Senator William Samuel Johnson

Here you will find contact information for Senator William Samuel Johnson, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | William Samuel Johnson |

| Position | Senator |

| State | Connecticut |

| Party | Pro-Administration |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | March 4, 1789 |

| Term End | December 31, 1791 |

| Terms Served | 1 |

| Born | October 7, 1727 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | J000182 |

About Senator William Samuel Johnson

William Samuel Johnson (October 7, 1727 – November 14, 1819) was an American Founding Father, jurist, educator, and statesman who played a prominent role in the political and constitutional development of the United States. A leading figure in both colonial and early national politics, he attended all four of the major “founding” American congresses: the Stamp Act Congress in 1765, the Congress of the Confederation from 1785 to 1787, the United States Constitutional Convention in 1787—where he chaired the Committee of Style that drafted the final version of the United States Constitution—and the first United States Congress, in which he served as a United States Senator from Connecticut from 1789 to 1791 as a member of the Pro-Administration Party. He also served as the third president of Columbia College (now Columbia University), and was widely regarded by contemporaries as a moderating, learned, and influential public figure.

Johnson was born in Stratford, Connecticut, on October 7, 1727, the son of the Reverend Samuel Johnson, a distinguished Anglican clergyman, philosopher, educator, and later president of King’s College in New York (the predecessor of Columbia University), and his first wife, Charity Floyd Nicoll. He received his early education under his father’s supervision at a small academy in Stratford that boarded students and offered a classical curriculum. He entered Yale College and graduated in 1744, earning the George Berkeley Scholarship, and quickly established himself as a promising scholar. He received a master’s degree from Yale in 1747 and, in the same year, an honorary degree from Harvard College, reflecting his early reputation in the colonies’ intellectual circles. His academic honors continued throughout his life: he received an honorary master’s degree from King’s College in 1761, a Doctor of Laws degree from the University of Oxford in 1766, and, after becoming president of Columbia College on May 21, 1787, he was awarded a Doctor of Laws degree there in 1788.

Although his father strongly encouraged him to enter the Anglican clergy, Johnson chose instead to pursue a legal career. Largely self-taught in the law, he rapidly developed a substantial practice in Connecticut and acquired clients and business connections that extended beyond the colony’s borders. He became a sought-after authority on intercolonial legal questions and built a reputation for careful reasoning and moderation. At the same time, he served in the Connecticut colonial militia for more than twenty years, rising from the rank of ensign to colonel. His public career in the colony’s government began with service as a deputy in the lower house of the Connecticut Legislature in 1761 and again in 1765, and he later served as a Governor’s Assistant (a member of the upper house, or colonial senate) from 1766 to 1775. These roles gave him extensive experience in legislative procedure and colonial administration.

In the 1760s Johnson was initially drawn to the Patriot cause by what he and many of his colleagues regarded as Parliament’s unwarranted interference in colonial self-government. In this period he could be counted among the more outspoken critics of British policy, writing of “chains and shackles,” “stamps and slavery,” and “late fatal acts” that would, in his view, reduce America to the status of “Roman provinces in the time of the Caesar.” He associated with the Connecticut Sons of Liberty and worked against the re-election of the Loyalist governor, Thomas Fitch. In 1765 he was elected one of three Connecticut delegates to the Stamp Act Congress in New York, where he served on the committee charged with defining the rights of British colonists and arguing for the colonies’ right to determine their own tax policies. According to his biographer E. Edwards Beardsley, Johnson “was a guiding and controlling spirit in the Assembly.” He authored the influential “Report of Committee at Congress on Colonial Rights,” which evolved into the Stamp Act Declaration of Rights and Grievances; the final version of this document is in his hand. He also served on the committee that drafted the Petition to the King. The combination of these colonial declarations, petitions, and economic pressure from British merchants contributed to Parliament’s repeal of the Stamp Act in 1766.

That same year, however, Connecticut confronted a longstanding legal dispute over Mohegan Indian lands, a case the British government appeared ready to use as a pretext to revoke the colony’s Royal Charter of 1662. Johnson agreed to serve as a special colonial agent to defend Connecticut’s charter and interests in London. Leaving his family, his political career, and his legal practice, he traveled to Britain in 1767 and remained there until 1771, while formally retaining his position as Assistant in the colony’s upper house. As colonial agent he sharply criticized British policy toward America, but his years in London convinced him that imperial policy was driven more by ignorance of American conditions than by deliberate malice. A scholar of international renown, he developed close friendships among British intellectuals and officials, including the English writer Samuel Johnson, who remarked that “of all those whom the various accidents of life have brought within my notice, there is scarce anyone whose acquaintance I have more desired to cultivate than yours.” Johnson’s religious ties to the Anglican Church and his academic connections, particularly with Oxford, which had honored him in 1766, further deepened his personal bonds with Britain. The Mohegan case, expected to last only a few months, dragged on for five years, during which he was separated from his family, lost much of his law practice, received little compensation or thanks, and endured criticism at home for his association with British authorities. He returned to Connecticut late in 1771, in time to spend three months with his father before the elder Johnson’s death, and was appointed a member of the colony’s Supreme Court, serving from 1772 to 1774.

As tensions between Britain and the colonies escalated, Johnson’s moderate stance placed him in a difficult position. In 1774 he was elected a delegate to the Continental Congress, but he declined the appointment in favor of his protégé, Roger Sherman. After the Battles of Lexington and Concord in 1775, the Connecticut Assembly, over Johnson’s strong personal objections, sent him through both Patriot and British lines to Boston to confer with General Thomas Gage in an effort to negotiate an end to hostilities and explore the possibility of a separate peace. He succeeded in securing terms, but upon his return to Connecticut he found that the Assembly had reversed course, voted for war, and adjourned without giving him further instructions. Even after the Declaration of Independence, Johnson believed that the American Revolution was unnecessary and that independence would be harmful to both Britain and the colonies. Disillusioned, he withdrew from the Assembly and from active legal practice. In July 1779, after British forces under General William Tryon burned the Connecticut coastal towns of Fairfield and Norwalk, panicked residents of Stratford implored Johnson to intercede with Tryon to spare their town. Initially he refused to undertake another dangerous mission he opposed, but a town meeting passed resolutions insisting that he go, and a committee was appointed to accompany him. A subscription paper implying his support for a peace effort was circulated without his consent; his political opponents seized upon this document, leading to his arrest on charges of communicating with the enemy. The charges were soon dropped, but the episode underscored the risks faced by moderates during the Revolution.

Once American independence was secured, Johnson felt free to participate fully in the new nation’s political life. He resumed his law practice and, sometime after the formal peace, was restored to his former position in the upper house of the Connecticut General Assembly. In that capacity he also served as legal counsel for Connecticut in its dispute with Pennsylvania over western lands in 1779–1780. His legal and political skills led to his appointment as a delegate to the Congress of the Confederation, where he served from 1785 to 1787. His influence in that body was widely recognized; the Connecticut financier Jeremiah Wadsworth wrote that “Dr. Johnson has, I believe, much more influence than either you or myself. The Southern Delegates are vastly fond of him.” In 1785 the Vermont Republic, grateful for his efforts in representing Vermont’s interests before the Confederation Congress, granted him a town in the former King’s College Tract. The town of Johnson, Vermont, the former Johnson State College, and Johnson Street in Madison, Wisconsin, all bear his name in recognition of his services.

In 1787 Johnson was chosen as one of Connecticut’s delegates to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, where he emerged as a key figure in the debates over representation and federal authority. He favored a strong national government that would protect small states like Connecticut from domination by larger neighbors and supported the New Jersey Plan, which called for equal representation of the states in the national legislature. He gave influential speeches on representation and strongly backed what became known as the Connecticut Compromise, a plan that anticipated the final Great Compromise by proposing a bicameral legislature with a Senate providing equal representation for all states and a House of Representatives apportioned by population. Johnson generally supported an expansive federal authority. He argued that the federal judicial power “ought to extend to equity as well as law,” a position reflected in the adoption of the phrase “in law and equity” at his motion. He contended that treason could not be committed against an individual state because sovereignty resided “in the Union,” and he opposed a blanket prohibition on ex post facto laws on the grounds that such a restriction implied an improper suspicion of the national legislature. In the final stages of the Convention, he served on and chaired the five-member Committee of Style, which was responsible for organizing and polishing the final text of the Constitution. His calm demeanor and scholarly reputation made him an ideal presiding figure over his fellow committee members Alexander Hamilton, Gouverneur Morris, James Madison, and Rufus King; historian Catherine Drinker Bowen later described him as “the perfect man to preside over these four masters of argument and political strategy,” noting that his “quiet manner disarmed” those around him.

Johnson’s national service continued under the new Constitution. When Columbia College (the former King’s College) in New York sought to revive its fortunes after the disruptions of the Revolution, he was elected its third president on May 21, 1787, a position he held concurrently with his political duties. Under his leadership, Columbia rebuilt its faculty, curriculum, and reputation, and he remained at its head until 1800, guiding the institution through its transition from a colonial Anglican college to a leading American university. Meanwhile, after the Constitution was ratified, the Connecticut legislature elected him to the United States Senate. He served as a Senator from Connecticut in the first United States Congress from March 4, 1789, to March 3, 1791, completing one term in office as a member of the Pro-Administration Party, which generally supported the policies of President George Washington and Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton. During this formative period of the federal government, Johnson contributed to the legislative process, participated in the establishment of the new government’s institutional framework, and represented the interests of his Connecticut constituents in debates over the organization of the federal judiciary, fiscal policy, and the implementation of the Constitution he had helped frame.

In his later years Johnson gradually withdrew from public life, devoting himself to scholarly pursuits, local affairs, and family in Stratford. He remained a respected elder statesman and a symbol of the generation that had guided the colonies from imperial crisis through revolution and constitutional founding to stable national government. William Samuel Johnson died in Stratford, Connecticut, on November 14, 1819, at the age of ninety-two. His long life spanned the transformation of British North America into the United States, and his contributions as lawyer, colonial agent, legislator, constitutional framer, senator, and college president left a lasting imprint on both the political institutions and educational foundations of the new nation.