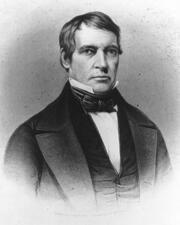

Senator William Rufus de Vane King

Here you will find contact information for Senator William Rufus de Vane King, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | William Rufus de Vane King |

| Position | Senator |

| State | Alabama |

| Party | Democratic |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | November 4, 1811 |

| Term End | December 20, 1852 |

| Terms Served | 10 |

| Born | April 7, 1786 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | K000217 |

About Senator William Rufus de Vane King

William Rufus DeVane King (April 7, 1786 – April 18, 1853) was an American politician and diplomat who served as the 13th vice president of the United States from March 4, 1853, until his death the following month. Over a long public career he served as a U.S. representative from North Carolina, a senator from Alabama, and minister to France under President James K. Polk. A Democrat and a Unionist, he was regarded by contemporaries as a moderate on the issues of sectionalism, slavery, and westward expansion that ultimately contributed to the American Civil War. He helped draft the Compromise of 1850 and is the only United States vice president from Alabama. He is also the only vice president in U.S. history to have taken the oath of office on foreign soil.

King was born on April 7, 1786, in Sampson County, North Carolina, to William King and Margaret DeVane. He was educated in local schools and graduated from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 1803, where he was a member of the Philanthropic Society, one of the university’s historic debating societies. After reading law under Judge William Duffy in Fayetteville, he was admitted to the North Carolina bar in 1805 or 1806 and began practicing law in Clinton, North Carolina. King was also a Freemason, reflecting his early integration into the civic and fraternal networks of his state.

King’s political career began in North Carolina state politics. He was elected to the North Carolina House of Commons, serving from 1807 to 1809, and in 1810 became city solicitor of Wilmington, North Carolina. At the national level, he was elected as a Democratic-Republican to the Twelfth, Thirteenth, and Fourteenth Congresses, representing North Carolina in the U.S. House of Representatives from March 4, 1811, until November 4, 1816. Only 24 years old when first elected, he did not reach the constitutional age of 25 until after his term began, but because the Twelfth Congress did not convene until November 4, 1811, he was not sworn in until that date, by which time he met the age requirement. He resigned from the House in 1816 to accept an appointment as secretary of legation to William Pinkney, then U.S. minister to Russia and to a special diplomatic mission in Naples, gaining early experience in foreign affairs.

Upon his return to the United States in 1818, King joined the westward movement of the cotton economy to the Deep South. He settled in the newly organized Alabama Territory, purchasing land on a bend of the Alabama River between present-day Selma and Cahaba in Dallas County, later known as “King’s Bend.” There he established a large cotton plantation, “Chestnut Hill,” worked by enslaved laborers. King and his relatives became one of Alabama’s largest slaveholding families, collectively owning as many as 500 enslaved people. He was a delegate to the convention that organized Alabama’s state government, and when Alabama was admitted as the twenty-second state in 1819, he was elected by the state legislature as a Democratic-Republican to the United States Senate.

William Rufus de Vane King served as a senator from Alabama in the United States Congress for much of the period from 1819 to 1852, contributing to the legislative process during what amounted to ten terms in office when his nonconsecutive service is considered. A follower of Andrew Jackson, he was reelected to the Senate as a Jacksonian in 1822, 1828, 1834, and 1841, serving continuously from December 14, 1819, until his resignation on April 15, 1844. During this long tenure he held several leadership roles. He was President pro tempore of the Senate during the 24th through 27th Congresses, and chaired the Committee on Public Lands and the Committee on Commerce. In March–April 1824, he received a token vote in the Democratic-Republican congressional caucus for the vice-presidential nomination, an early indication of his national prominence. In 1844 President James K. Polk appointed him minister to France, a post he held from 1844 to 1846. After returning to Alabama, King was again chosen for the Senate, being appointed and then elected to fill the vacancy caused by the resignation of Senator Arthur P. Bagby. He served in this second Senate period from July 1, 1848, until his resignation on December 20, 1852, when ill health and his election as vice president compelled him to step down. During the conflicts leading up to the Compromise of 1850, King supported the Senate’s gag rule against debate on antislavery petitions and opposed efforts to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia. While personally identified as a Unionist and political moderate, he defended slavery as constitutionally protected in both the Southern states and the federal territories, opposing both abolitionist proposals to restrict slavery in the territories and the radical “Fire-Eater” calls for Southern secession. On July 11, 1850, two days after President Zachary Taylor’s death, King was again appointed President pro tempore of the Senate; with Millard Fillmore having ascended to the presidency and the vice presidency vacant, this position placed King first in the line of presidential succession under the law then in effect. He also served as chairman of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations.

King’s national stature culminated in his nomination for the vice presidency in 1852. The Democratic National Convention met at the Maryland Institute for the Promotion of the Mechanic Arts Hall in Baltimore, where Franklin Pierce was nominated for president and King for vice president. The Democratic ticket of Pierce and King defeated the Whig candidates, General Winfield Scott and William Alexander Graham, in the general election. By this time, however, King was gravely ill with tuberculosis. Seeking a milder climate to restore his health, he traveled to Cuba and was unable to be in Washington, D.C., for the March 4, 1853, inauguration. By a special act of Congress approved on March 2, 1853, he was authorized to take the oath of office outside the United States, and on March 24, 1853, he was sworn in near Matanzas, Cuba, by William L. Sharkey, the U.S. consul. This made him the first and, to date, only vice president or president of the United States to take the oath of office on foreign soil. Because of his rapidly declining health, King never effectively carried out the duties of the vice presidency.

King’s personal life has attracted historical interest, particularly his long and close relationship with James Buchanan, later the 15th president of the United States. The two men, both lifelong bachelors, shared a residence in Washington for approximately thirteen years, from 1840 until King’s death in 1853, and were frequently seen together at official and social functions. Buchanan referred to their relationship as a “communion,” and contemporaries remarked on their intimacy. Andrew Jackson derisively called them “Miss Nancy” and “Aunt Fancy,” while Representative Aaron V. Brown referred to King as Buchanan’s “better half.” Some modern scholars, including biographer Jean Baker and writers such as Shelley Ross, James W. Loewen, and Robert P. Watson, have suggested that the relationship may have had a romantic dimension, though the surviving correspondence is guarded and much material was destroyed by family members. Other historians, such as Lewis Saum, caution that 19th-century social customs and language differed significantly from those of later eras and argue that the evidence supports, at minimum, a particularly close friendship rather than permitting definitive conclusions about its nature. After King’s death, Buchanan described him as “among the best, the purest, and most consistent public men I have known.”

In the final weeks of his life, King left Cuba and attempted to return to his Alabama plantation. Shortly after his oath-taking in March 1853, he traveled back to Chestnut Hill. He arrived there in April but was extremely weak, and he died of tuberculosis on April 18, 1853, at the age of 67, only 45 days after his term as vice president began. He thus became the third vice president to die in office, and only John Tyler and Andrew Johnson—both of whom succeeded to the presidency—have had shorter vice-presidential tenures. Following his death, the vice presidency remained vacant until John C. Breckinridge took office with President James Buchanan in March 1857. King was initially interred in a vault on his plantation. In 1882, after debate among family members and local officials, his remains were reinterred under a white marble mausoleum in Old Live Oak Cemetery in Selma, Alabama, a city he had helped found and named “Selma” after the Ossianic poem “The Songs of Selma.”

King’s legacy is reflected in several commemorations. In 1852, the Oregon Territorial Legislature named King County in his honor; that county later became part of Washington Territory and then the State of Washington. In 1985, the King County government redesignated its namesake to honor civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr., a change made legally official in 2005. At the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, his alma mater, the King Residence Quadrangle bears his name, and an 1830 portrait of him hangs in New East Hall in the Philanthropic Chambers of the Dialectic and Philanthropic Societies, the debating society he joined as a student. Through his long Senate service from Alabama, his role in major antebellum compromises, and his brief, historically unique tenure as vice president, William Rufus DeVane King played a notable part in the political life of the United States in the decades preceding the Civil War.