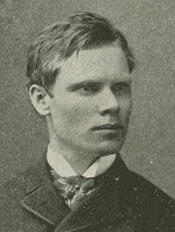

Representative William Sulzer

Here you will find contact information for Representative William Sulzer, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | William Sulzer |

| Position | Representative |

| State | New York |

| District | 10 |

| Party | Democratic |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | December 2, 1895 |

| Term End | March 3, 1913 |

| Terms Served | 9 |

| Born | March 18, 1863 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | S001065 |

About Representative William Sulzer

William Sulzer (March 18, 1863 – November 6, 1941), nicknamed “Plain Bill,” was an American lawyer and Democratic politician who served nine consecutive terms as a United States Representative from New York between 1895 and 1913 and was the 39th governor of New York in 1913. He became a prominent figure in Progressive Era politics and foreign affairs debates in Congress and later gained lasting historical note as the first, and to date only, New York governor to be impeached and the only governor of the state to be convicted on articles of impeachment.

Sulzer was born on March 18, 1863, and grew up in modest circumstances, an experience that helped shape his identification with popular causes and his later reputation as “Plain Bill.” He studied law, was admitted to the bar, and established himself as an attorney in New York City. Entering public life through the city’s vigorous and often contentious Democratic politics, he became associated with Tammany Hall, the powerful Democratic organization that dominated New York City and state politics in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. His early political rise was closely tied to this machine, even as his reformist inclinations would eventually bring him into conflict with it.

Sulzer was elected to the 54th United States Congress in 1894 and took his seat in the House of Representatives on March 4, 1895, representing New York’s 10th Congressional District. He remained in the House through the eight succeeding Congresses, serving continuously from March 4, 1895, to December 31, 1912. Over these nine terms, he contributed to the legislative process during a significant period in American history, participating in debates over imperialism, labor, and democratic reform, and representing the interests of his New York constituents. Known for his oratorical skill, he styled himself a “friend to all humanity and a champion of liberty,” and his speeches frequently reflected a strong sympathy for nationalist and democratic movements abroad.

During his congressional service, Sulzer emerged as an influential voice on foreign affairs and Progressive Era reforms. He supported the Cuban rebels during their War of Independence against Spain and, during the Second Boer War, introduced a resolution supporting the Boer republics and seeking to ban the sale of military supplies and munitions to the United Kingdom. He repeatedly called for resolutions condemning Czarist Russia for anti-Jewish pogroms and, in the Sixty-second Congress, chaired the House Committee on Foreign Affairs. From that position he proposed a resolution praising the Chinese Revolution of 1911, opposed United States intervention in the Mexican Revolution, and sponsored a unanimously supported bill to annul the Treaty of 1832 with Russia after that government refused to recognize the passports of Jewish Americans. Domestically, Sulzer supported key Progressive Era goals, including the creation of a United States Department of Labor, the direct election of U.S. senators—on which he introduced a supporting resolution—and the eight-hour workday. In the presidential election of 1896 he backed and campaigned for Democratic nominee William Jennings Bryan, aligning himself with the party’s populist and reform wing.

Sulzer’s ambition for higher office led him repeatedly to seek the governorship of New York. He first announced his candidacy for governor in 1896, but Tammany Hall and the broader Democratic Party rejected his bid. In 1898, Tammany leader Richard Croker openly opposed his attempt to secure the Democratic nomination, and over the next several election cycles Sulzer was continually passed over in favor of Tammany-backed candidates, including William Randolph Hearst and John Alden Dix. Despite these setbacks, he maintained a statewide profile as a reform-oriented Democrat. In 1912, a split between Republicans and Progressives made a Democratic victory in the gubernatorial race likely, and dissatisfaction among reformers with Governor Dix’s ties to Tammany created an opening. Reform Democrats, including State Senator Franklin D. Roosevelt, helped organize the Empire State Democracy Party to challenge Dix or any clear Tammany candidate. In this intra-party crisis, Sulzer emerged as a compromise nominee acceptable both to reformers and to Tammany. With the party united, and with the support of national figures such as William Jennings Bryan, William Randolph Hearst, and Woodrow Wilson, he was elected governor in November 1912, defeating Republican Job E. Hedges and Progressive candidate Oscar S. Straus. He resigned his seat in Congress effective December 31, 1912, to assume the governorship for the term beginning January 1, 1913.

Sulzer’s tenure as governor of New York in 1913 was brief but consequential. Almost immediately upon taking office, a rift developed between him and Charles F. “Silent Charlie” Murphy, Croker’s successor as Tammany Hall leader, when Sulzer asserted his own control over the state Democratic Party rather than deferring to Tammany’s authority. As governor, he pursued a reform agenda that included efforts to curb machine influence, but his break with his Tammany sponsors provoked a fierce backlash. Tammany leaders produced evidence that Sulzer had falsified his sworn statement of campaign expenditures, and the State Assembly moved against him. On August 13, 1913, the New York Assembly voted 79 to 45 to impeach Governor Sulzer. He was served with a summons to appear before the New York Court for the Trial of Impeachments, and Lieutenant Governor Martin H. Glynn was empowered to act in his place pending the outcome. Sulzer insisted the proceedings were unconstitutional and refused to acknowledge Glynn’s authority, but beginning August 21, Glynn began signing documents as “Acting Governor” despite Sulzer’s refusal to relinquish power.

Sulzer’s impeachment trial opened before the Impeachment Court in Albany on September 18, 1913. He retained prominent attorney Louis Marshall to lead his defense, though Marshall privately expressed doubts about the outcome. The proceedings did not go well for Sulzer; he did not testify in his own defense, and the evidence regarding his campaign finance reporting proved damaging. On October 16, 1913, the court convicted him on three articles of impeachment: filing a false report with the Secretary of State concerning his campaign contributions, committing perjury, and advising another person to commit perjury before an Assembly committee. The following day, October 17, 1913, by a vote of 43–12, the court ordered his removal from office, and Lieutenant Governor Glynn succeeded him as governor. Sulzer’s departure from Albany was marked by a large demonstration of supporters—contemporary accounts describe a crowd of about 10,000 outside the Executive Mansion—during which he denounced “criminal conspirators” and “looters and grafters” and expressed confidence that “the court of public opinion” and posterity would vindicate him. Some contemporaries argued that he had been impeached unfairly for acts committed before taking office, and in later years several bills were introduced in the New York State Assembly and Senate seeking to repair his political record, though none have been successful.

Despite his removal from the governorship, Sulzer managed a limited political comeback. Only weeks after his impeachment, he was elected to the New York State Assembly on the Progressive ticket and served in the 137th New York State Legislature in 1914, representing New York County’s 6th District. In the 1914 state election, he organized the American Party as a spoiler vehicle aimed at defeating Governor Glynn, his former lieutenant governor and successor, who was seeking re-election. Sulzer also sought the Progressive Party’s nomination for governor but lost in the primary, in part because former President Theodore Roosevelt publicly opposed him, writing to party members that “the trouble with Sulzer is that he does not tell the truth.” Sulzer then accepted the Prohibition Party’s nomination for governor in 1914, after delivering a speech denouncing alcohol, and finished third in the general election behind Republican Charles S. Whitman, who was elected governor, and Democrat Martin H. Glynn, who was defeated. Sulzer nonetheless claimed a moral victory, arguing that the Democrats who had impeached him had been swept from power. In the 1916 presidential election he was the presidential nominee of the American Party, further underscoring his continuing, if diminished, role on the political fringe.

In his later years, Sulzer gradually withdrew from electoral politics and returned to the practice of law in New York City. He continued to write and speak on public questions and developed an interest in religious and philosophical movements. After meeting ʻAbdu’l‑Bahá during his visit to the United States in 1912, Sulzer became a sympathetic commentator on the Baháʼí Faith and occasionally spoke and wrote in its support from the 1920s onward. William Sulzer died in New York on November 6, 1941, at the age of 78. He was buried at Evergreen Cemetery in Hillside, New Jersey, closing a career that had spanned the height of the Progressive Era, the tumult of New York machine politics, and one of the most notable impeachment episodes in American state political history.