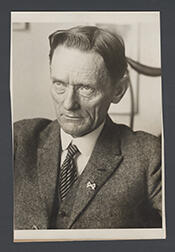

Representative William David Upshaw

Here you will find contact information for Representative William David Upshaw, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | William David Upshaw |

| Position | Representative |

| State | Georgia |

| District | 5 |

| Party | Democratic |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | May 19, 1919 |

| Term End | March 4, 1927 |

| Terms Served | 4 |

| Born | October 15, 1866 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | U000026 |

About Representative William David Upshaw

William David Upshaw (October 15, 1866 – November 21, 1952) was an American politician, temperance advocate, and Baptist lay leader who served as a Democratic Representative from Georgia in the United States Congress from 1919 to 1927. Over four consecutive terms, he represented Georgia’s 5th Congressional District and became nationally known as one of the most uncompromising supporters of Prohibition, earning the sobriquet “the driest of the drys.” His congressional career, closely intertwined with the temperance movement and the politics of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s South, later led him to run for President of the United States on the Prohibition Party ticket in 1932, when he finished in fifth place.

Upshaw was born on October 15, 1866, and spent his formative years in the Reconstruction-era South, an environment that shaped his later views on race, religion, and states’ rights. As a young man, he suffered a debilitating injury that left him partially crippled for much of his life, a circumstance he later described in his 1893 book, “Earnest Willie, Or Echoes From A Recluse,” published by Franklin Printing and Publishing Co. This work, reflecting his experiences of physical suffering and religious conviction, helped establish his reputation as a moral reformer and public speaker in Southern Protestant circles before he entered national politics.

By the early twentieth century, Upshaw had become deeply involved in the temperance movement and in Southern Baptist life. His oratorical skills and fervent advocacy of Prohibition earned him the nickname “the Billy Sunday of Congress” once he reached the national stage, a reference to the famous evangelist Billy Sunday. He was closely associated with leading figures in Southern Protestantism, including evangelist Bob Jones Sr., who later founded Bob Jones College (which evolved into Bob Jones University). Upshaw would go on to serve on the Board of Trustees of Bob Jones College from its founding in Lynn Haven, Florida, in 1927 until 1932, when he was dropped from the board for failing to attend annual meetings or file his voting proxies.

Upshaw entered electoral politics at the federal level in 1918, when incumbent Democrat William S. Howard retired from Georgia’s 5th District seat in the U.S. House of Representatives to run for the United States Senate. Running as a Democrat, Upshaw secured the nomination and faced no opposition in the general election. He took office in 1919 and served four terms, remaining in Congress until 1927. During his tenure, he was a prominent supporter of Prohibition legislation and worked closely with organizations such as the Anti-Saloon League, from which he received payments that later became a point of political controversy. He also advocated for the creation of a United States Department of Education and focused on what he regarded as the protection of American schools from “alien doctrines,” including Bolshevism, reflecting his broader anti-radical and socially conservative outlook.

A defining and highly controversial aspect of Upshaw’s congressional career was his relationship with the Ku Klux Klan. The Klan had been reorganized in his congressional district, and Upshaw emerged as one of its most vocal defenders in Congress, though he consistently denied being a formal member. Internal Klan newsletters claimed he was a member, and the Georgia Historical Society later concluded that, although never definitively proven, there was “little doubt” that he belonged to the organization. Upshaw was in frequent contact with Klan leaders in Georgia and became an important political ally of the group. During a congressional investigation into Klan activities, he publicly defended the organization, declaring that he felt a “wounded pride” at the criticisms directed at the Klan, which he noted had been organized in his district, and praising its imperial wizard as one of the “knightliest, most patriotic men” he had ever known. He suggested that Congress investigate all secret societies, such as the Masons, a move that may have contributed to the early conclusion of the Klan probe.

Upshaw’s alignment with the Klan and his broader racial and states’ rights positions were further underscored in 1922, when he strongly opposed a federal anti-lynching bill. He delivered several speeches against the legislation, employing racially charged language and arguing that such matters should remain under state jurisdiction. He emerged as a key political leader resisting federal efforts to curb Klan violence and racial terror. These positions, once politically advantageous in parts of the South, became liabilities as national scandals engulfed the Klan in the mid-1920s. In the 1926 Democratic primary, his opponent, Leslie Jasper Steele, effectively tied Upshaw to the Klan’s misconduct and highlighted revelations that Upshaw had received financial support from the Anti-Saloon League, suggesting that his Prohibition advocacy was driven by monetary motives. Upshaw lost the primary, failed to secure the Democratic nomination for a fifth term, and left Congress in 1927.

After his congressional career ended, Upshaw remained active in religious and political life. In 1927 he was elected a vice president of the Southern Baptist Convention, serving two terms in that capacity and using his position to continue promoting temperance and conservative social causes. He made repeated attempts to revive his political career, the most notable being his 1932 candidacy for President of the United States on the Prohibition Party ticket, with Frank S. Regan of Illinois as his running mate. Running in a year when public sentiment was turning decisively against national Prohibition, Upshaw’s ticket finished fifth in the general election, far behind Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt, who favored repeal of Prohibition, Republican incumbent Herbert Hoover, Socialist candidate Norman Thomas, and Communist candidate William Z. Foster. A decade later, in 1942, Upshaw sought the Democratic nomination for the U.S. Senate from Georgia but again failed to secure his party’s endorsement.

In his later years, Upshaw moved to California, where he devoted himself to lecturing, writing, and ministering as a Christian evangelist. In 1938, at the age of 72, he was ordained a Baptist minister and became vice president and a teacher at Linda Vista Baptist Bible College and Seminary in San Diego. His religious and charitable activities in California included collaboration with Roy Davis, a leading Klan figure, in an effort to establish an orphanage in San Bernardino County. The project ended in scandal when it was revealed that Davis had defrauded donors, further tarnishing the reputations of those associated with the venture. Upshaw continued to cultivate a public image as a man of faith and perseverance, even as his earlier political alliances and controversies remained part of his legacy.

In 1952, at age 85 and only months before his death, Upshaw attracted national attention by claiming he had been miraculously healed at a revival meeting conducted by evangelist William Branham. Long known for his physical disability and reliance on crutches, Upshaw asserted that he had regained the ability to walk unaided. He sent a letter describing this claimed healing to every member of Congress, and the story was widely reported in the press, including the Los Angeles Times. In interviews, he acknowledged that he had been able to walk short distances without crutches before the Branham meeting but insisted that his strength had markedly improved and that he could now walk much farther without assistance. William David Upshaw died on November 21, 1952, in Glendale, California, at the age of 86, and was buried at Forest Lawn Memorial-Park, closing a life that spanned Reconstruction, the Prohibition era, and the early Cold War, and that left a complex and controversial imprint on American religious and political history.