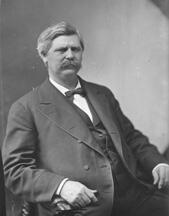

Senator Zebulon Baird Vance

Here you will find contact information for Senator Zebulon Baird Vance, including email address, phone number, and mailing address.

| Name | Zebulon Baird Vance |

| Position | Senator |

| State | North Carolina |

| Party | Democratic |

| Status | Former Representative |

| Term Start | December 7, 1857 |

| Term End | March 3, 1895 |

| Terms Served | 5 |

| Born | May 13, 1830 |

| Gender | Male |

| Bioguide ID | V000021 |

About Senator Zebulon Baird Vance

Zebulon Baird Vance (May 13, 1830 – April 14, 1894) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 37th and 43rd governor of North Carolina, a U.S. senator from North Carolina, and a Confederate officer during the American Civil War. A prolific writer and noted public speaker, he became one of the most influential Southern leaders of the Civil War and Reconstruction eras. As a leader associated with the “New South,” Vance favored the rapid modernization of the Southern economy, railroad expansion, school construction, and reconciliation with the North. A member of the Democratic Party in his mature political career, he contributed to the legislative process during multiple terms in office and was widely regarded as a dominant figure in North Carolina politics. A Philosemite, he frequently spoke out against antisemitism and defended Jewish citizens in public addresses. Considered progressive by many during his lifetime, Vance was also a slave owner and an outspoken defender of slavery before and during the Civil War, and he is now regarded as a racist by some modern historians and biographers.

Vance was born in a log cabin in the settlement of Reems Creek in Buncombe County, North Carolina, near present-day Weaverville, and was baptized at the Presbyterian church on Reems Creek. He was the third of eight children of Mira Margaret Baird and David Vance Jr., a farmer and innkeeper. His paternal grandfather, David Vance, served as a colonel in the American Revolutionary War under George Washington at Valley Forge and was a member of the North Carolina House of Commons, while his maternal grandfather, Zebulon Baird, was a state senator from Buncombe County. His uncle was Congressman Robert Brank Vance, namesake of Zebulon’s elder brother, Congressman Robert B. Vance. The family moved around 1833 to Lapland, now Marshall, North Carolina, where his father operated a stand supplying drovers along the Buncombe Turnpike. Although often short of cash, the family enslaved as many as eighteen people, and Vance himself was reared in part by Venus, a house slave. The household possessed an unusually large library for its time and place, inherited from an uncle, which helped shape Vance’s intellectual development.

Vance’s early education began at about age six in schools operated by M. Woodson, Esq., first at Flat Creek and later on the French Broad River, both far enough from home that he boarded with others. He also attended a school in Lapland run by Jane Hughey. As a youth he suffered a serious injury when he fell from a tree and broke his thigh; the leg was treated by confining him in a box, a common medical practice of the era. The result was a shortened right leg that required a higher heel on his right shoe and produced what contemporaries described as a “peculiar and slightly ambling gait.” In the fall of 1843, at age thirteen, he enrolled at Washington College in Tennessee, but his father died in January 1844 in a construction accident, forcing Vance to withdraw before the end of the school year. His mother sold much of the family’s property to pay debts and support her seven surviving children, moving them to nearby Asheville along with enslaved women and children as household workers. Lacking funds to return to Tennessee, Vance and his brother Robert attended Newton Academy in Asheville.

To help support his family, Vance worked as a hotel clerk for John H. Patton in Warm Springs (now Hot Springs), North Carolina. He then read law in Asheville under attorney John W. Woodfin. At age twenty-one he wrote to family friend David L. Swain, former governor of North Carolina and then president of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, seeking assistance to pursue formal legal study. Swain arranged a $300 loan from the university, enabling Vance to enroll at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in July 1851. He had what contemporaries described as a “brilliant academic year.” Classmates recalled his rustic appearance on arrival—homemade clothes and shoes with several inches of bare ankle showing—but also his “large and active” mind, tenacious memory, and wide-ranging knowledge. At Chapel Hill he joined the Dialectic Society, which honed his oratorical and extemporaneous speaking skills, and became a member of the Phi Gamma Delta fraternity. He received a law degree (LL.D.) in 1852 and repaid the university loan with interest. Afterward he went to Raleigh to continue his legal training with Judge William Horn Battle of the North Carolina Supreme Court and with Samuel F. Phillips, later Solicitor General of the United States.

On January 1, 1852, Vance was admitted to the North Carolina bar and received his county court license in Raleigh. He returned to Asheville to practice law, traveling to court on horseback with a change of shirts and a copy of the North Carolina Form Book in his saddlebags. The Buncombe County magistrates soon elected him solicitor of the Court of Pleas, and he was admitted to practice in the state’s superior courts in 1853. In 1858 he formed a partnership with attorney William Caleb Brown. Though he did not always prepare his cases with thoroughness, Vance was known for his keen ability to read juries and recall testimony in detail; his courtroom success rested largely on his wit, humor, forceful and sometimes boisterous eloquence, and quick retorts rather than on technical mastery of the law. His legal work, combined with his growing reputation as a speaker, helped launch his political career.

Vance entered politics as a Whig, canvassing for Whig presidential candidate Winfield Scott in 1852. In 1853 he represented Buncombe County at a railroad convention in Cumberland Gap, Tennessee, which sought to persuade the Charleston and Cincinnati Railroad to route a line through the mountains of western North Carolina. He was elected as a Whig to the North Carolina Senate for a term beginning in December 1854. Identifying himself with the Whig tradition of Henry Clay, he later wrote that he had been “raised in the Whig faith” and taught to revere Clay and Daniel Webster. In the state legislature he concentrated on transportation issues important to western North Carolina, introducing a bill for a public road in Yancey County, supporting subscriptions to fund the French Broad and Greenville Railroad, and advocating extension of the Western North Carolina Railroad into the mountain counties along a route from Asheville to Knoxville, Tennessee. After the national Whig Party collapsed over slavery in the mid-1850s, Vance refused to join either the predominantly Southern Democratic Party or the antislavery Republicans, instead aligning with the nativist American (Know-Nothing) Party. He lost his 1856 bid for reelection to the state senate to David Coleman.

Alongside his legal and legislative work, Vance briefly pursued journalism. In March 1855 John D. Hyman of the Asheville Spectator persuaded him to join the weekly Whig newspaper as an editorial assistant, predicting a “brilliant career in the editorial line.” Within a year Vance left his role as joint editor but became half-owner of the paper. The Spectator’s strong support for Vance, often in sharp exchanges with the rival Asheville News, significantly aided his political fortunes. Among his notable pieces was a detailed account of the 1857 search for Dr. Elisha Mitchell, his former geology professor at the University of North Carolina, who fell to his death while attempting to determine the highest peak in North Carolina. Vance volunteered for the search party, and his published narrative in the Spectator became the most complete contemporary record of the episode.

In 1858 Vance sought national office, running for the U.S. House of Representatives in a special election to fill the vacancy created by the resignation of Thomas Lanier Clingman. Conducting a vigorous fifteen-county speaking tour that “set the mountains on fire,” he won the seat and took office in December 1858. At age twenty-eight he was the youngest member of Congress at the time. He was reelected in 1859, defeating his former opponent David Coleman. During his House service he was outspoken on fiscal matters, opposing a proposal to grant each representative a $10,000, or 25 percent, increase in fringe benefits with a colorful comparison to hotel bills padded with “sundries.” He criticized chronic Treasury deficits in similarly vivid terms, insisting that the nation must either increase tariff revenues, reduce expenditures, or face insolvency. During this period he was firmly pro-slavery, arguing in March 1860 that enslaved people should remain in “servitude” and describing bondage as their “normal condition,” while urging humane treatment within the institution.

Despite his defense of slavery, Vance initially opposed secession and urged North Carolina to remain in the Union while preserving slavery. Writing to a friend, he warned that hasty secession might forfeit an irreplaceable “heritage” and argued that the state had “everything to gain and nothing on earth to lose by delay.” He nevertheless supported the call for a secession convention so that North Carolinians could decide the issue themselves. In March 1861 he traveled across the state campaigning against immediate secession. His stance changed abruptly in April 1861 when news arrived, as he addressed a large crowd, of the firing on Fort Sumter and President Abraham Lincoln’s call for 75,000 volunteers. Vance later recalled that he then became a secessionist, preferring, as he put it, to “shed northern rather than southern blood.” He resigned from Congress after the outbreak of hostilities and returned to Buncombe County to take up arms for the Confederacy.

On May 4, 1861, two weeks before North Carolina formally seceded, Vance raised a local company known as the Rough and Ready Guards and was elected its captain. The unit became Company F of the 14th North Carolina Infantry and encamped near Morganton, North Carolina, before being sent by June 1861 to Suffolk, Virginia, to assist in the defense of Norfolk. In August 1861 Vance was elected colonel of the 26th North Carolina Infantry Regiment, stationed at Fort Macon in Carteret County. He led the 26th at the Battle of New Bern in March 1862, where, though outnumbered four to one, his troops held Union forces at bay for five hours and were the last Confederates to leave the field. During the subsequent thirty-five-mile retreat he displayed personal bravery, nearly drowning while swimming across the flooded Bryce’s Creek to secure boats for his men; the three soldiers who swam with him drowned. In July 1862 he commanded the regiment at the Battle of Malvern Hill outside Richmond, Virginia. Although the Confederates were defeated, Vance again exhibited what contemporaries described as “unflinching leadership,” and his name quickly emerged as a candidate for governor when North Carolina sought new leadership.

In 1862 Vance ran for governor of North Carolina as the “soldier’s candidate” and won overwhelmingly against secessionist Democrat William J. Johnston of Charlotte. He did not leave his troops to campaign, make speeches, or issue a formal platform; instead, he published a letter in the Fayetteville Observer stating that if his fellow citizens believed he could better serve “the great Cause” as governor than in the field, he would not feel at liberty to decline the responsibility, despite his own sense of unworthiness. His campaign was managed by William W. Holden of the North-Carolina Standard and Edward J. Hale of the Fayetteville Observer, both leaders of the Conservative Democratic coalition of former Whigs and Democrats who opposed the original secession movement. Holden urged voters to “elect the man who defended their homes,” contrasting Vance, then in the trenches, with Johnston, whom he portrayed as safely at home tending his railroad interests. The Democratic administration was blamed for high prices, conscription, military defeats, soldiers’ suffering, and suspension of habeas corpus, all of which aided Vance. He received 54,423 of 74,871 total votes, carrying all but twelve counties—the largest margin of victory in a North Carolina gubernatorial race. Serving with the 26th North Carolina in the trenches at Petersburg, Virginia, when he learned of his election, Vance resigned his commission and traveled to Raleigh to assume the governorship at age thirty-two.

Vance’s later political career centered on his long association with the Democratic Party and his service in the United States Senate. Although the existing record here inaccurately suggests that he served as a senator from 1857 to 1895, his principal tenure in the U.S. Senate came after the Civil War and Reconstruction. As a Democratic senator from North Carolina in the late nineteenth century, he participated actively in the legislative process over multiple terms, representing the interests of his state during a period of rapid industrialization, sectional reconciliation, and the entrenchment of Jim Crow racial policies in the South. In Washington he was known for his oratory, his advocacy of internal improvements and public education, and his efforts to promote economic development in North Carolina, particularly through railroad expansion. At the same time, his record reflected the racial attitudes of his era and region; while he publicly opposed antisemitism and defended Jewish citizens, he supported white supremacy and the continued political and social dominance of whites in the postwar South.

Throughout his life, Vance remained a prominent public figure in North Carolina and the broader South, widely read and frequently invited to speak on history, politics, and regional identity. His writings and speeches contributed to the development of the “Lost Cause” narrative and to the ideology of the New South, blending calls for modernization with defenses of Southern traditions. He died on April 14, 1894, leaving a complex legacy as a wartime governor, influential senator, and powerful voice in Southern politics whose advocacy of economic progress and religious tolerance coexisted with his defense of slavery and racial hierarchy.